Queensland's approach to Indigenous health equity planning and implementation should align with existing international frameworks

The Australian state of Queensland is embedding Indigenous‐led strategies to advance health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter respectfully referred to as Indigenous people) on paper and in practice. However, critical gaps remain.1,2 Making tracks together: Queensland's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health equity framework,3 released by the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council and Queensland Health in 2021, is the catalytic framework driving the state's Indigenous health equity agenda. It seeks to “actively eliminate racial discrimination and institutional racism, and influence the social, cultural and economic determinants of health by working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, health services, communities, consumers and Traditional Owners” to design, deliver, monitor and review health care services.4

Implementation of the Making Tracks Together framework became law in April 2021 after the Queensland Parliament passed an amendment to the Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld).5 This instructs that Queensland's 16 hospital and health services (HHSs) must embed an Indigenous health equity strategy and, under section 40 (1)(c) of the Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011, every HHS must consult with its health professionals, consumers, Indigenous community members, and the Indigenous community‐controlled health sector for strategy development.5,6 An Indigenous Health Equity Strategy Toolkit and Template is available from Queensland Health to support co‐designed strategic planning and implementation by the HHSs and their partners.4 The Health Equity Strategy Toolkit suggests six key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure priority areas as identified in the legislation, with implementation timeframes (Box 1).

With the Health Equity Strategy Toolkit and its KPIs in hand, the next question for HHSs is how to optimally analyse the rich information collected in the mandatory consultancy phase. Findings from that analysis are important because they will provide HHSs with an evidence base to identify and shape the targets and priorities for action under the six broadly worded KPIs.7

Applying the AAAQ (available, accessible, acceptable, quality) framework

A practical way in which HHSs can begin their analysis of the data collected through the consultation process is through a review of place‐based community experiences of access to safe, appropriate and timely health services. To unpack the various health service access complexities in these data, HHSs could draw on the AAAQ framework, released by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2000.8 The AAAQ framework sets out four interconnected and essential elements for health service access — that health services are available, accessible, acceptable and quality — as directed under international right to health law.8 The AAAQ framework is a practical, conceptual and operational tool to explore enablers and barriers to equitable health service access for accountable and transparent health equity policy, planning and action at both the health service and systems level.9,10 This includes access to health facilities, goods and services, and the underlying determinants of health.8

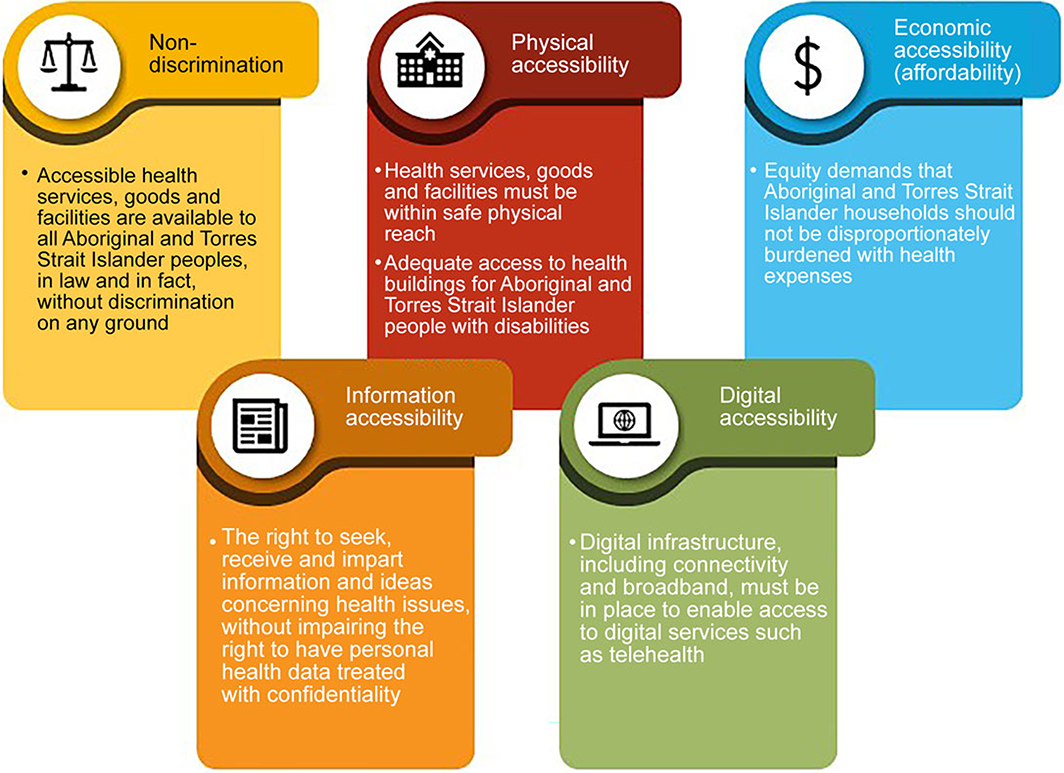

By drawing on the AAAQ framework, HHSs could review the information collected through consultations to examine whether public health services are available in sufficient quantity for Indigenous people living in the service area. Here, it will be particularly important that HHSs engage with Indigenous consumers of primary health care services to respectfully identify local HHS access blocks and continuity of care needs between primary and tertiary health care facilities. Then, applying the framework's second element, HHSs could explore whether health services are accessible to local Indigenous people without discrimination. In determining health service accessibility, the framework guides exploration of four overlapping dimensions: physical, economic and information accessibility, and non‐discrimination.8 Considering Queensland's geographic vastness, physical accessibility of health services will likely elicit questions about the local community's access to emergency air transport services. Additionally, improving information accessibility for culturally safe, appropriate access to relatively complex services requiring more extensive support, such as clinical genetics and medical genomics services, is crucial.11,12

In addition to the existing four accessibility dimensions in the AAAQ framework, digital accessibility (and the digital determinants of health) also needs consideration for comprehensive Indigenous health equity planning (Box 2).13,14,15 Telehealth is becoming more permanent in Australia,16 and exploring opportunities for improved digital accessibility has potential to mitigate accessibility barriers to certain health services for Indigenous people living in rural, remote and very remote Queensland, if telehealth is what the local community wants. In examining questions of digital accessibility and availability, multijurisdictional issues will arise; the Australian Government is responsible for National Broadband Network roll‐out in all states and territories, not the Queensland Government.17 Additionally, acceptable and quality telehealth service provision to and with Indigenous communities will be key, and local community guidance is crucial to inform what this might look like in practice.

The final two elements of the AAAQ framework are acceptable and quality health services. In the context of Indigenous health equity strategic planning, HHSs could analyse the consultancy data to examine whether their services are acceptable to local Indigenous people in terms of place‐based cultural acceptability, and whether health services are respectful of medical ethics, sensitive to dimensions such as gender, ability and other appropriate life cycle requirements, and designed to respect confidentiality. Finally, health facilities, goods and services within HHSs for Indigenous people must be of good quality for health equity achievement. This means local health services must be culturally appropriate, be staffed with skilled medical personnel, provide patients with scientifically approved and unexpired drugs and medications, and have quality equipment. Adequate sanitation, safe water and energy supplies that promote the determinants of health are also necessary.8 Indigenous staff and their inclusion in the health workforce, and the way they are supported in health careers and health management roles, should also be part of systemic assessments into health access, equity, and quality.

The AAAQ framework can help identify less obvious barriers to timely access

Another reason Queensland HHSs might draw on the AAAQ framework is because application of an AAAQ lens can support community, public health researchers and policymakers bring to light and describe the more sensitive and nuanced health service access complexities that contribute to health inequity. It is the less visible access barriers and injustices that exist within larger institutions and in health systems, including racial discrimination, which Queensland's Indigenous health equity reform agenda keenly seeks to address at the local level through KPI 2 (Box 1). This is because access to health services under the AAAQ framework cannot be considered separate and distinct from health service availability, acceptability and quality: all four AAAQ elements are essential, and overlap and interrelate.8,9,10 For example, a health service might be available on paper, but it is not accessible in practice because the Indigenous health consumer has a disability and is unable to access the health service building or cannot access a computer in an appropriate space for a confidential telehealth consultation. In turn, the health service might be accessible in theory, but administrative staff or health worker behaviour may be viewed as discriminatory or not culturally acceptable by the local community. Thus, that health service may not be accessible in practice to local Indigenous community members. Alternatively, a health service might be available, accessible and acceptable on paper, but not a quality health service. This is because local community members might have serious, well founded concerns about the confidentiality of their personal and health information (for example, that the information is being improperly shared with other government agencies outside of Queensland Health without the health consumer's knowledge or permission). Where there is legitimate concern about health service quality, such services may again be available and accessible on paper but not in practice for local Indigenous people and communities.

Conclusion

Access to health services that are culturally safe and responsive, equitable and free of racism for all Indigenous people is central to the achievement of Indigenous health equity in Queensland and across Australia.18 Understanding place‐based health service access enablers and barriers, community priorities and needs will be imperative to enable HHSs to finalise their Indigenous health equity KPIs and planning. Returning to community to respectfully check that the KPIs in the draft strategy accurately reflect the community consultation will be key. Once the strategic plan has been finalised, equally important will be the inclusive establishment of local, multistakeholder participatory advisory groups to support, as well as monitor and review, timely HHS strategy implementation. Local participatory advisory groups will help generate accountability and transparency around Indigenous health equity planning and implementation, which is imperative for HHS achievement of KPI 6 (Box 1).

However, access to health services for Indigenous people is more than a KPI priority pursuant to new regulation under the Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld) — it is a matter of fundamental human dignity. Unlike in other states and territories, Indigenous people's access to public health services is also a human right under section 37 of the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld).19 According to section 37, everyone in Queensland has the right to access health services without discrimination, and as public entities under that Act, all HHSs are obliged to facilitate immediate access to culturally safe Queensland Health services without discrimination.20,21 HHSs must bear this in mind should they identify the existence of direct or indirect discrimination at the service and systems level when planning and implementing their Indigenous health equity strategic plans. Under section 37 (1) of the Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld), any discriminatory treatment of Indigenous people in policy or practice requires immediate action and redress.

Box 1 – Six key performance indicators (KPIs) to deliver improved health and wellbeing outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples throughout Queensland4

- KPI 1: Improving health and wellbeing outcomes

- KPI 2: Actively eliminating racial discrimination and institutional racism within health care services

- KPI 3: Increasing access to health care services

- KPI 4: Influencing the social, cultural and economic determinants of health

- KPI 5: Delivering sustainable, culturally safe and responsive health care services

- KPI 6: Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, communities and organisations to design, deliver, monitor and review health services

Box 2 – Five overlapping dimensions of health service accessibility in the AAAQ* framework, with examples

AAAQ = available, accessible, acceptable, quality.8

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Milligan L, Selvaratnam N, Day L. Women who died after going to Doomadgee Hospital with a preventable disease were ‘badly let down’, minister says. ABC News 2022; 8 March. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022‐03‐08/doomadgee‐hospital‐health‐service‐rhd‐women‐deaths/100887674 (viewed Mar 2022).

- 2. Office of the Health Ombudsman (Queensland). Review into the quality of health services provided by Bamaga Hospital. Brisbane: Office of the Health Ombudsman, 2020. https://dxcgqpir544a8.cloudfront.net/reports/Investigation‐report‐Bamaga‐hospital‐FINAL20200824.pdf?mtime=20200914150935&focal=none (viewed Mar 2022).

- 3. Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council and Queensland Health. Making Tracks Together: Queensland's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Equity Framework. Brisbane: QAIHC and QH, 2021. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/1121383/health‐equity‐framework.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 4. Queensland Health. First Nations health equity. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/public‐health/groups/atsihealth/making‐tracks‐together‐queenslands‐atsi‐health‐equity‐framework (viewed Feb 2022).

- 5. Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld) (current as at 1 July 2022). https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/inforce/current/act‐2011‐032 (viewed Nov 2022).

- 6. Queensland Health. First Nations health equity strategies (Health Service Directive no. QH‐HSD‐053:2021). https://www.health.qld.gov.au/system‐governance/policies‐standards/health‐service‐directives/first‐nations‐health‐equity‐strategies (viewed Nov 2022).

- 7. Braveman PA. Monitoring equity in health and healthcare: a conceptual framework. J Health Popul Nutr 2003; 21: 181‐192.

- 8. United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General comment no. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). Geneva: UN, 2000. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 9. Hunt P, MacNaughton G. Impact assessments, poverty and human rights: a case study using the right to the highest attainable standard of health (Health and Human Rights Working Paper Series No. 6). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006.

- 10. Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, et al. Health systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet 372: 2047‐2085.

- 11. Dalach P, Savarirayan R, Baynam G, et al. “This is my boy's health! Talk straight to me!” perspectives on accessible and culturally safe care among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients of clinical genetics services. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 103.

- 12. Kowal E, Gallacher L, Macciocca I, Sahhar M. Genetic counseling for Indigenous Australians: an exploratory study from the perspective of genetic health professionals. J Genet Couns 2015; 24: 597‐607.

- 13. Crawford A, Serhal E. Digital health equity and COVID‐19: The innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e19361.

- 14. Kaihlanen, A‐M, Virtanen L, Buchert U, et al. Towards digital health equity – a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by vulnerable groups in using digital health services in the COVID‐19 era. BMC Health Serv Res 2022; 22: 188.

- 15. Backholder K, Baum F, Finlay SM, et al. Australia in 2030: what is our path to health for all? Med J Aust 2021; 214 (8 Suppl); S1‐S40. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/214/8/australia‐2030‐what‐our‐path‐health‐all

- 16. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Permanent telehealth for all Australians. 16 December 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/news/permanent‐telehealth‐for‐all‐australians (viewed Feb 2022).

- 17. Australian Government Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. NBN policy information. https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/media‐technology‐communications/internet/national‐broadband‐network/nbn‐policy‐information (viewed Feb 2022).

- 18. Australian Government Department of Health. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/12/national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐plan‐2021‐2031_2.pdf (accessed March 2022).

- 19. Queensland Legislation. Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld). https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act‐2019‐005 (viewed Aug 2022).

- 20. Brolan CE. Queensland's new Human Rights Act and the right to access health services. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 158‐160. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/213/4/queenslands‐new‐human‐rights‐act‐and‐right‐access‐health‐services

- 21. Forman L et al. What could a strengthened right to health bring to the post‐2015 health development agenda?: interrogating the role of the minimum core concept in advancing essential global health needs. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013; 13: 48.

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley – The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This article was written as part of the “Advancing non‐discriminatory, rights‐based access to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” project funded by National Health and Medical Research Council Ideas Grant no. 2004327.

Claire Brolan is a member of the Academic Advisory Group, Queensland Human Rights Commission. Maree Toombs sits on the Board of Carbal Medical Services (Aboriginal Medical Service) in the Darling Downs region, Queensland.