The known: Workplace teaspoon loss is rapid: an estimated 0.99 per 100 days in one study in an academic research institute.

The new: The rates of disappearance of eating utensils in a public teaching and research hospital staff tearoom differed by type, being more pronounced for teaspoons than for forks. Utensil rebirth or resurrection is a real phenomenon, particularly for forks and knives.

The implications: Teaspoon migration appears to be a more substantial problem than fork disappearance. Further investigation of the epidemiology of utensil migration is warranted.

As our team approached the festive season, thoughts of fun, food and frivolity pervaded the workplace. Access to spoons and forks in institutional tearooms provides functional, wellbeing, and hygiene benefits to staff. In response to personal experience and landmark research that identified a significant and rapid loss of teaspoons in an institutional setting,1 we hypothesised that loss of forks was of equal or greater concern than for other cutlery items. The aim of our study was therefore to evaluate the circulation lifespan of forks, and to compare it with that of teaspoons in a hospital multidisciplinary tearoom. Secondary aims and benefits of the project were linked with our organisational Values in Action,2,3 including teamwork and high performance: that is, an efficient tearoom and publication in a high impact journal!

Methods

Our longitudinal quality improvement study was conducted at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, the largest public teaching and research hospital in Queensland; specifically, in the Critical Care and Clinical Support Services Directorate and the Intensive Care Services staff tearoom, used by nursing, medical, administration and research staff and by professional visitors to the area. The tearoom (3.8 m × 4.4 m) has a sink and hot water unit, two microwave ovens, a refrigerator, a dishwasher, several cupboards, and seating for eight people. Utensils are stored on the benchtop in three cutlery stands.

We introduced 18 stainless steel forks and 18 stainless steel teaspoons marked with indelible red dots (OPI Got the Blues for Red nail lacquer) into the existing stock of utensils (Box 1). To minimise bias, staff and visitors to the tearoom (apart from the authors) were blinded to the intent and conduct of the study. The numbers of marked forks and teaspoons present in the tearoom were measured twice weekly over seven weeks (Tuesday and Friday afternoons), with careful searching of the dishwasher and all potential concealed locations in the tearoom. The numbers of unmarked knives, forks, spoons and teaspoons in the tearoom were measured at baseline and at study completion (45 days later).

No a priori sample size calculations were made. The proportions of forks and teaspoons at the conclusion of the study were compared in a χ2 test. Kaplan–Meyer analysis of all‐cause survival of marked cutlery, censored at day 45, was planned, but not undertaken because of the observed “rebirth” and “resurrection” of utensils reported below.

Ethics approval

Exemption from formal ethics review was sought and obtained from the hospital human research ethics committee (HREC). When considering this important health care matter, the HREC chair acknowledged that “cutlery, and in particular fork, disappearance within institutions remains one of the central conundrums [of] our time… Not restricted to hospitals, this phenomenon has also been seen in Australian public service departments, where the disappearance of teaspoons led to comments in national newspapers.4” Nor is the phenomenon restricted to Australia.5 Further, “the proposed study, based in Intensive Care Services, seems an appropriate usage of departmental resources given the benefits that it is likely to have on health: inability to eat meals at lunchtime could lead to afternoon fatigue and decreased work efficiency;6 using spoons instead of forks to eat, for example, salad, could lead to damage to teeth and also to increased spillage, which would have an economic and possibly workplace health and safety impact, given the possibility of slippage on foodstuffs and the need to clean up any spillage. Other conceivable benefits would be to work productivity through increased morale and decreased corridor inquisitions about who took the fork” (personal communications, 20 August 2019).

Finally, the HREC chair commented that “the investigators are evidently endeavouring to provide some explanation for the kleptomaniacal vicissitudes of Intensive Care Services staff and visitors. Normally, and in order not to produce any undesired stress among staff, the investigators would be asked to alert people to the study through the use of flyers, posters, or word of mouth. However, doing so would invalidate any results as it may lead to conscious behavioural changes. Therefore, there is the possibility for some deceptive conduct on the part of the investigators. The ethical implications are not vast, but any potential for distress at being deceived can be obviated by dissemination of the outcomes of the study once completed. The study is teleological in nature, with the telos in this case resembling that of Plato’s happiness.7 In addition, it is adopting Benthamic utilitarianism as an outcome,8 seeking the greatest good for the greatest number. It fails the test of deontology as it does not propose to use methodology that would be acceptable to all persons. In summary, as the benefits would appear to outweigh the risks, and as the study is being conducted in accordance with Values in Action,2,3 this study is approved for a quality improvement exercise and therefore exempt from full ethics review.”

Results

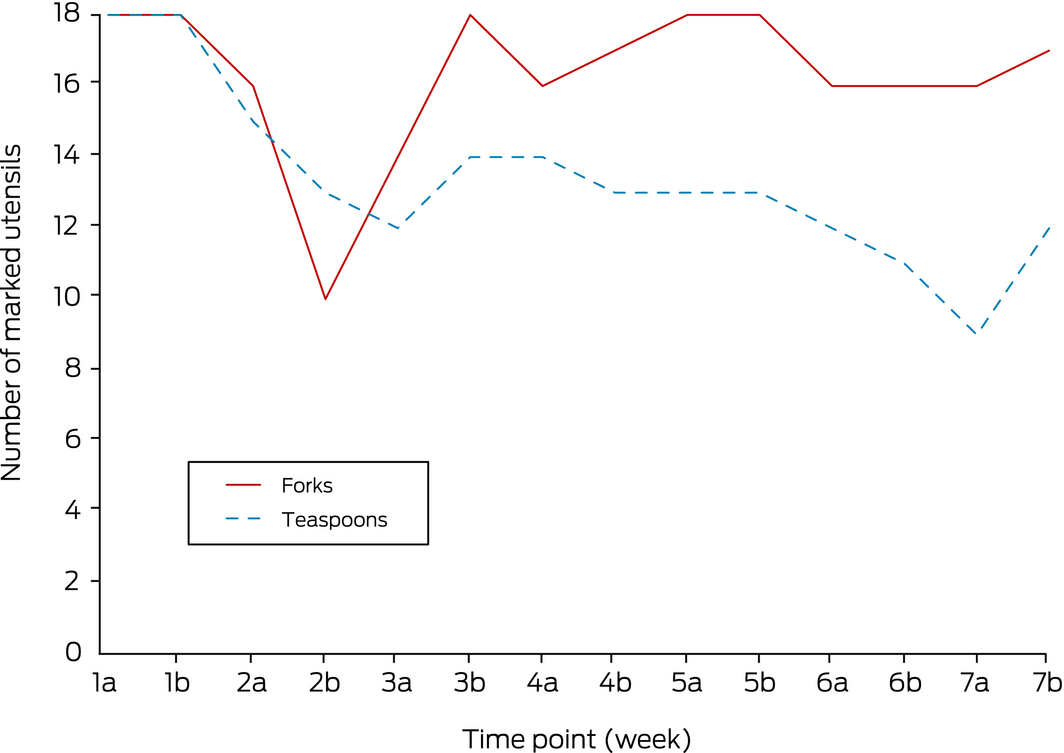

We found a statistically significant difference in the proportions of introduced (marked) utensils still present at the end of the study; six marked teaspoons and one marked fork were missing (P = 0.038). This was in stark contrast to unmarked cutlery, with increases over the study period for both teaspoons (five) and forks (two) (Box 2). The greatest reduction in marked utensils was at the second week 2 count, followed by some recovery in week 3 (Box 3). At the conclusion of the study period, the overall rate of utensil loss (marked and unmarked) was 2.2 per 100 days for teaspoons and spoons and –2.2 per 100 days for forks and knives.

Discussion

We found that when marked forks and teaspoons were introduced into the shared tearoom environment of a public teaching and research hospital, teaspoon attrition (six of 18) statistically exceeded that of forks (one of 18) over the 45‐day study period. The increases in unmarked fork, teaspoon, and knife numbers led the authors to contemplate whether introducing new utensils had an attractive effect on unmarked utensils, or whether it would have been better to conduct the study during Easter, when resurrection is a recognised and documented phenomenon.9

Another possible explanation for the attrition of marked and the increase in unmarked cutlery numbers could be that the Got the Blues for Red nail lacquer used to mark cutlery may have succumbed to the abrasive and cleaning actions of the dishwasher and All‐in‐1 Finish Powerball dishwasher tablets. However, this would not fully explain the variations observed, as the total number of each utensil type changed across the study period. Specific testing of the effects of dishwashing on the nail lacquer markings on the cutlery would be required to ensure that it is truly indelible in future trials.

The time series for the marked utensils is also interesting, as the count of marked forks had dropped substantially at the second week 2 time point, but rapidly recovered during week 3. This pattern also applied, although less clearly, to the marked teaspoons. These utensils may have been victims of kleptomania or individual expropriation, or the forks and spoons may have been used for a morning or afternoon tea celebration in the Intensive Care Services offices and not returned until cleaned perfectly by an obsessive member of staff. The study would benefit from measuring potentially confounding events as well as utensil counts.

We found a consistent pattern of teaspoon attrition in a public teaching and research hospital that was higher (2.2 per 100 days) than in the academic research institute in the landmark study on the subject1 (0.99 per 100 days). While the authors of the earlier study measured differing disappearance rates of teaspoons according to tearoom communality and utensil value, the resurrection phenomenon noted in our study was not reported. This leads us to conclude that the epidemiology of utensil migration requires multicentre global evaluation for greater generalisability.

Limitations

Our study had a number of limitations that deserve mention. There may have been unmeasured confounding factors, such as unrecorded celebratory events, that affected our findings. While criminal history checks are conducted for all staff during pre‐employment screening, the sensitivity and specificity of the recruitment process for detecting tearoom kleptomaniacal tendencies is unknown. While our longitudinal analysis provides important insights into utensil presence at a single location, it leaves unanswered the question of where the cutlery goes.

A continuous observation time‐and‐motion study with a larger discretionary budget, undertaken in a hospital with location grade WiFi and tracking technology,10 could more specifically map the location of cutlery. Radiofrequency identification chips11 applied to sentinel utensils could provide conclusive evidence as to whether disappearing utensils are removed from or merely redistributed within the facility.

Conclusion

Our study provides evidence that teaspoon migration is a more substantial problem than fork disappearance in a multidisciplinary staff tearoom, suggesting differing kleptomaniacal tendencies or individual appropriation patterns by cutlery type. We therefore recommend giving teaspoons, not forks, as gifts in office “secret Santa” parties this Christmas. As rebirth or resurrection is a real phenomenon for certain utensil types, the use of forks may be inherently symbolic of Christmas (or Easter) and they are intrinsically useful for celebratory cake eating this Yuletide.

- Mark Mattiussi1,2

- Amelia Livermore1

- Annabel Levido1

- Therese Starr1,3

- Melissa Lassig‐Smith1,3

- Janine Stuart1

- Cheryl Fourie1,3

- Joel Dulhunty1,2

- 1 Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 Centre for Clinical Research, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

This study was undertaken with in kind support by the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Critical Care and Clinical Support Services Directorate; Cheryl Fourie contributed OPI Got the Blues for Red nail lacquer. We extend special thanks to Gordon McGurk, chair of the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, whose insightful comments feature in our report.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Lim MS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK. The case of the disappearing teaspoons: longitudinal cohort study of the displacement of teaspoons in an Australian research institute. BMJ 2005; 331: 1498–1500.

- 2. Metro North Hospital and Health Service (Brisbane). Vision and values. Updated July 2018. https://metronorth.health.qld.gov.au/about-us/vision-and-values (viewed July 2020).

- 3. Metro North Hospital and Health Service (Brisbane). Shaun Drummond: values in action at Metro North HHS [video]. 8 May 2018. https://vimeo.com/268523248 (viewed July 2020).

- 4. Moore C. Australia’s “Shawshank redemption”: Some of the country’s most violent criminals use spoons and forks to remove bricks from their cell before plans to dig their way out are thwarted. Daily Mail Australia, 16 Sept 2019. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7467087/Australias-Shawshank-Redemption-Prisoners-caught-digging-Port-Phillip-Prison.html (viewed July 2020).

- 5. Hoyle C. Who stole all the forks? The science of missing office cutlery. Stuff (Wellington, New Zealand), 15 Apr 2017. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/91303980/who-stole-all-the-forks-the-science-of-missing-office-cutlery (viewed July 2020).

- 6. Leedo E, Beck AM, Astrup A, Lassen AD. The effectiveness of healthy meals at work on reaction time, mood and dietary intake: a randomised cross‐over study in daytime and shift workers at an university hospital. Br J Nutr 2017; 118: 121–129.

- 7. Morrison D. The happiness of the city and the happiness of the individual in Plato’s Republic. Ancient Philosophy 2001; 21: 1–24.

- 8. Kelly PJ. Utilitarianism and distributive justice: the civil law and the foundations of Bentham’s economic thought. Utilitas 1989; 1: 62–81.

- 9. Murphy N. Immortality versus resurrection in the Christian tradition. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011; 1234: 76–82.

- 10. Nuño‐Maganda MA, Herrera‐Rivas H, Torres‐Huitzil C, et al. On‐device learning of indoor location for WiFi fingerprint approach. Sensors (Basel) 2018; 18: 2202.

- 11. Hornyak R, Lewis M, Sankaranarayan B. Radio frequency identification‐enabled capabilities in a healthcare context: an exploratory study. Health Informatics J 2016; 22: 562–578.

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the circulation lifespan of forks and teaspoons in an institutional tearoom.

Design: Longitudinal quality improvement study, based on prospective tracking of marked teaspoons and forks.

Setting: Staff tearoom in a public teaching and research hospital, Brisbane.

Participants: Tearoom patrons blinded to the purposes of the study.

Intervention: Stainless steel forks and teaspoons (18 each) were marked with red spots and introduced alongside existing cutlery (81 items) in the tearoom.

Main outcome measures: Twice weekly count of marked forks and teaspoons for seven weeks; baseline and end of study count of all utensils on day 45.

Results: The loss of marked teaspoons (six of 18) was greater than that of forks (one of 18) by the conclusion of the study period (P = 0.038). The overall rate of utensil loss was 2.2 per 100 days for teaspoons and spoons, and –2.2 per 100 days for forks and knives.

Conclusions: Teaspoon disappearance is a more substantial problem than fork migration in a multidisciplinary staff tearoom, and may reflect different kleptomaniacal or individual appropriation tendencies. If giving cutlery this Christmas, give teaspoons, not forks. The symbolism of fork rebirth or resurrection is appropriate for both Christmas and Easter, and forks are also mighty useful implements for eating cake!