In the digital age, health practitioners need to be not only producers but also curators and disseminators of accurate and timely information

In late 2019, Kirsty Forrest (Dean of Medicine at Bond University) invited me to speak at the Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand annual conference via a direct message on Twitter. She had listened to a number of episodes of the MedEdStuffnNonsense podcast I co‐host with Tanya Selak, produced by Stuart Marshall.

In these episodes, we had discussed a “dangerous idea” in medical education: that medical schools must change their current approach to social media, away from either being ignored entirely or advising an abstinence approach and toward proactive teaching of responsible, effective use of social media integrated within curricula. We argued that Hippocrates would be on Twitter and, therefore, so should we. This was in recognition that Hippocrates, the accepted father of modern medicine, outlined in the Hippocratic Oath what many view as a professional and “moral compass”, including broad and ethical sharing of medical knowledge.

The focus of this article is on Twitter as the principal social media platform embraced globally by health care and science professionals to freely communicate with each other, journalists, politicians and the public to openly share expert information.

So, would Hippocrates really be on Twitter?

Hippocrates’ teachings included that knowledge sharing was fundamental. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has resulted in an important need to share academic and clinical information immediately with experts across professions as well as with patients. This need is well addressed by Twitter, which is open to all and has global reach. Thus, we believe now more than ever, Hippocrates would be on Twitter and so should we. Education of how to responsibly use social media platforms is thus essential.

Conversely, many medical education and health care organisations have felt that Twitter and other social media and online sources are uncontrolled and a threat to traditional medical education.1 Most have overemphasised the negative aspects of social media by taking a conservative approach and teaching regulatory obligations but not how to embrace the technology for education purposes.

Change is scary, but we are already here. The most dangerous phrase in the English language, indeed in any language, is “we’ve always done it this way”.2 For us, stagnation poses the most danger. We argue that it is unethical for health care professionals to not be on Twitter.

Professional communities of practice

We all need connection and community for academic and professional practice as well as wellbeing, and yet our traditional communities have faded. Attendance at medical school lectures and meetings had been dwindling and has needed to be primarily online during 2020 due to COVID‐19. Twitter provides a virtual space for health professionals to connect with each other across traditional specialty and professional silos as well as geographical locations. It can also flatten hierarchies, and experts can model professional behaviour and include patients in the conversation. COVID‐19 has created an unprecedented opportunity for the wider use and acceptance of Twitter in the medical community.

A new approach to knowledge management

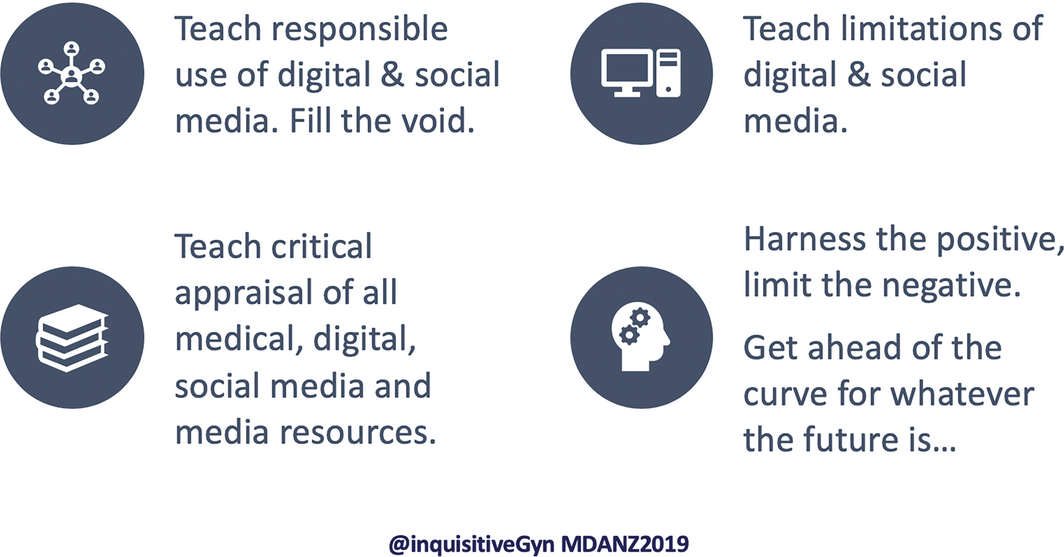

Historically, it was possible for doctors to learn and know “everything”. In 1950, medical knowledge had an estimated doubling time of 50 years.3 There has been an exponential increase in knowledge and, before COVID‐19, the projected doubling time in 2020 was 73 days.3 However, it is likely that it is much shorter with the upsurge of information related to public health and virology in the first 4 months of this year. We have not and cannot change our cognitive ability to learn more. We therefore need to maximise our ability to curate and access knowledge. Just as we teach clinical reasoning and critical appraisal of traditional health care literature, we need to do this for all sources of information, including Twitter. We need to teach how to responsibly discuss ideas publicly with each other and how to safely converse with journalists, influencers and consumers online (Box).

Research and scholarship

Twitter allows prompt dissemination and discussion of research, knowledge and education. This results in content being available for rapid translation, as well as real time peer review.4 This extends the impact across traditional and geographical silos to include more diverse voices from across specialties and health care professions and, most importantly, includes patients. The downside may be the dissemination of misinformation if experts are not present to provide correction.

Managing risks and dangers

The inherent risks and dangers of social media are well described. An awareness of and adherence to regulations such as the Medical Board and the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) social media policy,5 and those of any organisations we are employed by or represent, are essential. In many respects, safe and responsible social media use mirrors real‐life professional behaviour. Users can model and learn respectful behaviour, learn how to discuss clinical problems openly and confidentially, advocate for patients as well as address scientific learning and connection. “Don’t do it” is not a valid or ethical solution. A brief yet comprehensive 12‐word social media policy from the Mayo Clinic covers the salient points:

“Don’t Lie, Don’t Pry

Don’t Cheat, Can’t Delete

Don’t Steal, Don’t Reveal”6

What would Hippocrates suggest?

In health care, we now need to be curators and disseminators of accurate and timely information not solely producers. We need to harness the positive and limit the negative while getting ahead of the curve for whatever the future holds. It is time we teach ourselves and our students how to engage responsibly on social media. We, the community and our patients will be better for it. This is particularly evident now during the COVID‐19 pandemic, where our need for timely and accurate information has never been greater.

Hippocrates is credited with saying “there are two things, science and opinion; the former begets knowledge, the latter ignorance”. Yes, there is opinion on the internet, and if we as health care professionals are not there to address factually incorrect opinions and have a respectful discourse and teach, we are complicit in ignorance.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Roland D, Brazil V. Top 10 ways to reconcile social media and “traditional” education in emergency care. Emerg Med J 2015; 32: 819–822.

- 2. Schieber P. The wit and wisdom of Grace Hopper. OCLC Newsletter 1987; 167. http://www.cs.yale.edu/homes/tap/Files/hopper-wit.html (viewed Sept 2019).

- 3. Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2011; 122: 48–58.

- 4. Brazil V, Parker C. A day in the life: social media for clinical practice and medical education. Med J Aust 2017; 206: 478–480. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/206/11/day-life-social-media-clinical-practice-and-medical-education

- 5. Medical Board and Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Social media: how to meet your obligations under the National Law [website]. https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Policies/Social-media-guidance.aspx (viewed Dec 2019).

- 6. Timimi FA. A 12‐word social media policy. Mayo Clinic Social Media Network, 2012. https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2012/04/05/a-twelve-word-social-media-policy/2012 (viewed Sept 2019).

This article is based on a presentation to the Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand (MDANZ) at the University of Melbourne on 20 September 2019. I acknowledge Kirsty Forrest and MDANZ for the invitation to speak and our MedEdStuffnNonsense podcast team: Tanya Selak and Stuart Marshall, and podcast guests: Laura Duggan, Rachel Lewin and Charlotte Durand. I thank Tanya Selak, Stuart Marshall and Victoria Brazil for their review of this article. MedEdStuffnNonsense episodes 17, 23, 27 and 28 were used to compile the MDANZ presentation on which this reflection article is based. The presentation was published in full on Twitter as a thread on 20 September 2019 (https://twitter.com/inquisitiveGyn/status/1174926537662984192?s=20).

No relevant disclosures.