The known: Emergency aeromedical retrievals of people with mental health problems from rural and remote areas of Australia have not been investigated in detail.

The new: During 2014–2017, the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) transported 2257 patients from rural and remote locations to large towns and cities for the treatment of mental and behavioural disorders. The major working diagnoses for these patients were schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, and depression.

The implications: The dearth of dedicated clinical mental health support and intervention services in remote Australia dissuades many people from seeking help until they are in crisis.

Rates of suicide and of mental health problems are higher in rural and remote regions than in metropolitan areas of Australia.1,2,3,4 The misuse of psychostimulant drugs, including amphetamine and methamphetamine,5 is also widespread in rural and remote locations, and a disproportionate number of hospital presentations related to amphetamine‐type stimulants are by Indigenous people in rural and remote Australia.6

Rural and remote areas have fewer health services than metropolitan areas,7,8,9,10,11,12 including considerably fewer psychologists and psychiatrists.11,12 The comparative lack of support for mental health services in these communities has been attributed to lower numbers of people at risk, and to their not seeking assistance except during crises or after moving to metropolitan areas for definitive management.

The reasons for transferring rural and remote patients from their communities to metropolitan hospitals for treatment of mental and behavioural disorders have not been well investigated. In particular, we believe that the number of aeromedical retrievals by the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) of people with mental and behavioural disorders, especially of younger patients, has increased over the past three years, but little has been published on this question.

The RFDS is funded by the federal and state governments and by private donations. In addition to its fixed wing aeromedical retrieval service, the RFDS provides extensive road transport services for patients (inter‐hospital transfers, and from flights to receiving hospitals), mainly in Victoria, New South Wales, and Tasmania. The RFDS also provides extensive primary health care services throughout Australia (Supporting Information, figure), including primary care (general practice), nursing, and dental health clinics, as well as mental health services.13

The primary aims of our study were to describe the types of mental and behavioural disorders for which people are retrieved by the RFDS, to provide basic epidemiologic data about these patients (numbers, age, sex, Indigenous status), and to assess the availability of mental health care by RFDS and non‐RFDS services in rural and remote areas. Our goal was to provide a comprehensive picture of the mental health problems and complications experienced by rural and remote Australians that precipitate acute aeromedical transfers to metropolitan centres.

Methods

We undertook a prospective review of routinely collected data to determine the types of mental and behavioural disorders leading to aeromedical retrieval of patients by the RFDS, the basic demographic features of these patients, and the rural and remote retrieval locations and the major city destinations involved. We included data for all patients who were retrieved during the three years 1 July 2014 – 30 June 2017 by the RFDS from anywhere in Australia (except Tasmania) for the treatment of mental or behavioural disorders (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth edition [ICD‐10], chapter V).

Data recorded electronically included patient demographic information and medical history, aeromedical working diagnosis, locations of retrieval and receipt, and service provider and type. Multiple transfer legs were combined as single episodes of care for analysis. Patient data collection forms and systems differ between RFDS sections and operations, but all collect data for the same variables. Most information (including diagnoses) was collected freehand during the RFDS flight and later transferred to electronic databases; the working diagnosis was re‐coded according to ICD‐10 categories.

“Rural and remote area” was defined as including all areas outside major cities according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Areas (ASGS‐RA) classification system.14

Health Direct (https://about.healthdirect.gov.au) data on the locations of health services throughout Australia (including non‐RFDS mental health services) was used in conjunction with health care service data not included in the Health Direct database (such as the location of RFDS clinics) obtained from RFDS clinical databases. The RFDS has an agreement with Health Direct that allows access to their data. Mental health services included community services with mental health clinical support, community health centres, child and adolescent mental health services, public and private hospitals, mental health rehabilitation services, and mental health services specific to alcohol and drug misuse. We overlaid clinic locations with 2016 census data provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to assess mental health clinical care coverage by population.

We determined mental health service coverage with the RFDS Service Planning and Operational Tool (SPOT) for exploring health care coverage in rural and remote Australia. Based on the geographic distribution of demand and the set of health care facilities that provide a range of corresponding services, SPOT calculates the level of demand covered by those facilities for people within a specified distance; for example, within one hour's drive by motor vehicle. Demand includes population levels of demand in certain categories (eg, mental health services) as well as some specific RFDS demand types (retrievals).

To identify general practitioners with Focussed Psychological Strategies (FPS) skills training accredited by the General Practice Mental Health Standards Collaboration (GPMHSC),15 we reviewed GPMHSC accreditation and registration data (status: 11 October 2018).

We report our data as summary descriptive statistics. All statistical analysis was conducted in Excel (Microsoft) and the software package R 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Retrieval and receiving sites were mapped with ArcMap (Environmental Systems Research Institute) and Tableau mapping software.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Australian Capital Territory Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, 2018/QA/00184).

Results

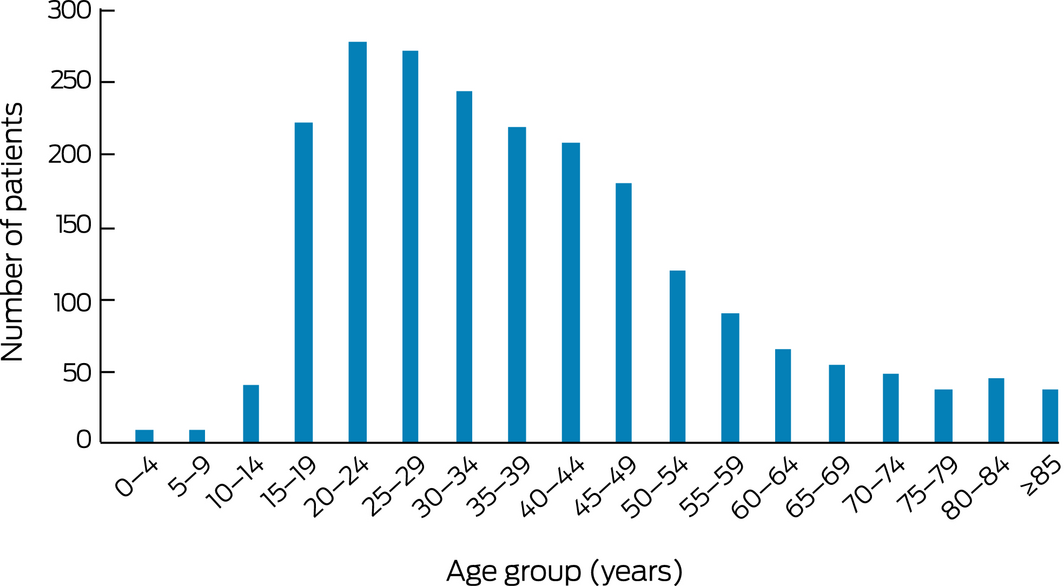

Between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2017, the RFDS transported 71 232 patients. This number included 2257 people (3.2%) transported to metropolitan hospitals for treatment for mental and behavioural disorders: 1365 males (60%) and 892 females (40%); 793 (35%) identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Australians: 477 males (60%) and 316 females (40%). The number of aeromedical retrievals of patients with mental and behavioural disorders increased from 309 (2.7% of retrievals) in 2014–15 to 1038 (3.6%) in 2016–17 (Box 1). Most patients (1302 of 2192 with age data, 59%) were under 40 years of age (Box 2); their mean age was 37.0 years (standard deviation [SD], 19.3 years). Most patients (2167, 96%) received one aeromedical retrieval for mental or behavioural disorders, 83 (3.7%) two, and seven (0.3%) were retrieved three or more times.

Most aeromedical clinical teams consisted of an RFDS nurse (1151, 51% of retrievals), an RFDS doctor and nurse (585, 26%), or a non‐RFDS doctor and an RFDS nurse (171, 7.6%). Flight authorisation times, collected for all patients, were evenly distributed across the 24‐hour day (data not shown). Data on distance flown was available for 1362 retrievals (60%); the mean distance covered was 406 km (SD, 279 km), the median distance was 324 km (interquartile range, 298 km).

Diagnoses: overall

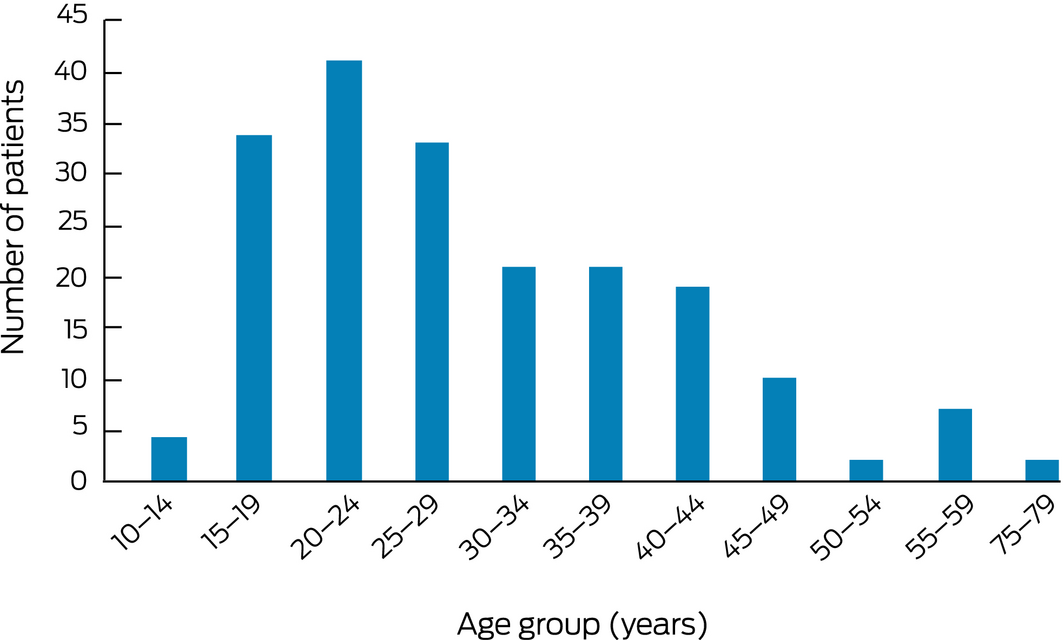

Most patients (1367, 60.6%) received a detailed (ICD‐10) working diagnosis; for 890 patients (39.4%), a generic diagnosis only (eg, “mental disorder”) was recorded. The most frequent ICD‐10 diagnoses were schizophrenia (227 retrievals, 16.5% of retrievals with ICD diagnoses), bipolar affective disorder (185, 13.5%), and depressive episodes (153, 11.2%). The most frequent ICD diagnoses by block were schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20–F29; 522, 38.2%), mood (affective) disorders (F30–F39; 409, 30.0%), and mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–F19; 194, 14.2%). Psychoactive substance misuse triggering retrievals included multiple drug (85 retrievals, 6.2%), alcohol (61, 4.5%), and cannabinoid misuse (25, 1.8%) (Box 3). The mean age of the 194 patients retrieved for treatment of substance misuse‐related problems (29.6 years; SD, 11.6 years) was lower than for that for all retrieval patients, with the distribution shifted to younger age groups (112 of 194 [58%] under 30 years of age) (Box 4).

Diagnoses: younger patients (0–24 years of age)

The most frequent reason for retrieval of people aged 14 years or younger was dysfunctional mood dysregulation disorder (ICD: bipolar affective disorder) (73 of 98 retrievals with ICD diagnoses, 74%); the most frequent reasons for retrieval of people aged 15–24 years were schizophrenia (48 of 310 retrievals with ICD diagnoses, 16%), unspecified non‐organic psychosis (39, 13%), and depressive episodes (37, 12%). A total of 69 mental health‐related retrievals of people aged 15–24 years (24%) were associated with substance misuse (multiple drug use, 36 [12%]; alcohol, 22 [7.1%]; cannabinoids, 11 [3.5%]) (Box 5). Thirty‐eight of the 194 patients retrieved for treatment for substance misuse (19.6%) were aged 19 years or younger.

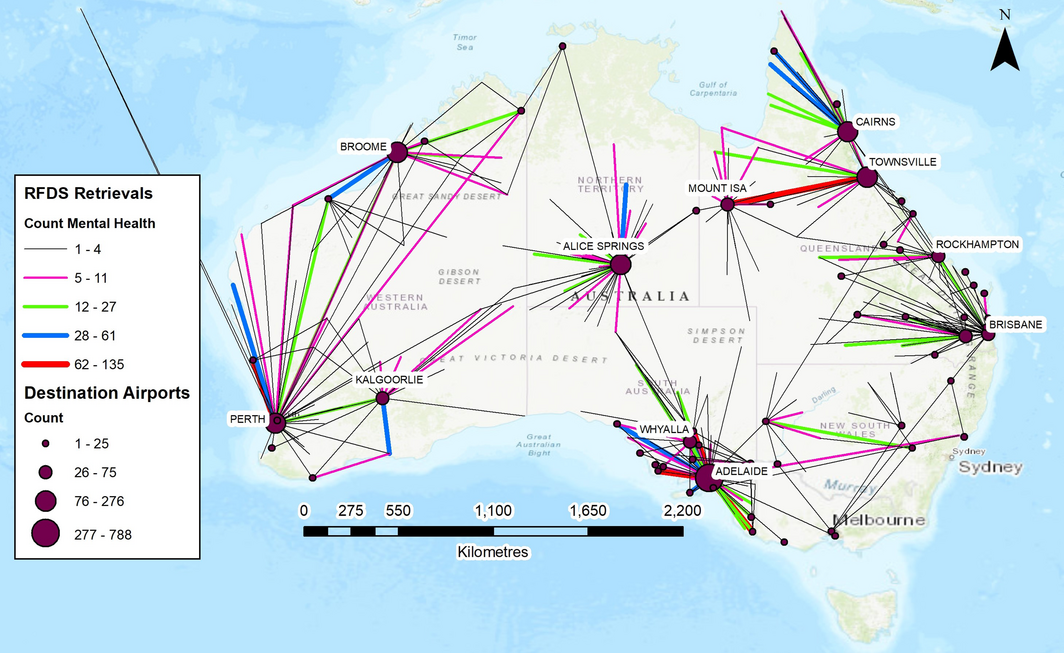

Transfer origins and destinations

Most patient transfers were from rural and remote regions to metropolitan areas (Box 6). The most frequent rural and remote retrieval communities were Port Augusta (138 retrievals), Port Pirie (96), Mount Gambier (79) and Port Lincoln (79) in South Australia, and Mount Isa in Queensland (74). Most receiving sites were metropolitan and inner regional cities, including Adelaide (803 retrievals), Perth (275), Cairns (188), Alice Springs (182), and Townsville (134).

Mental health care services

Mental health care provision by non‐RFDS services was considerably more restricted in rural and remote areas than in metropolitan areas; for example, 723 of 1029 FPS‐trained general practitioners were located in major cities (70.3%), 282 (27.4%) in inner and outer regional areas, and 24 (2.3%) in remote and very remote areas.

The RFDS provided general practitioner and nursing fly‐in‐fly‐out clinics in areas with markedly lower levels of non‐RFDS mental health services, where the RFDS was often the only service provider. Most patients in rural and remote areas would need to travel by motor vehicle for more than 60 minutes to reach the nearest RFDS or non‐RFDS mental health services (many of these services are also general practitioner or nurse‐led clinics) (Supporting Information, figure). The highest population regions in which coverage by non‐RFDS mental health clinical services is limited are listed in the table in the online Supporting Information.

Discussion

Rural and remote patient aeromedical care transfers for mental and behavioural illnesses have been little investigated. The leading causes for RFDS mental health retrievals were of patients transferred from rural and remote to metropolitan areas for more definitive care for schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, or depression.

These results are consistent with our earlier finding11 that many RFDS retrievals are from areas that have low levels of health services. The numbers of general practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health nurses, and social workers are low in many rural and remote areas, as are those of emergency departments and hospitals.11

The rates of general practitioner‐prepared mental health treatment plans are much lower in rural and remote areas than in metropolitan areas.16 This may be partly explained by the fact that many rural and remote areas receiving block funding for mental health care services. Further, the dispensing rates of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme‐listed psychotropic medications are lowest in remote areas, probably because of the scarcity of pharmacies. For instance, the dispensing rates for antipsychotic agents are similar in inner (13 503 [low socio‐economic status areas] to 22 683 prescriptions [high socio‐economic status areas] per 100 000 people aged 18–64 years) and outer regional areas (13 702 to 20 407 per 100 000) to those in major cities (14 299 to 20 151 per 100 000), but they are markedly lower in remote communities (6910 to 10 768 prescriptions per 100 000).16 Antipsychotic medications are important for treating schizophrenia and related disorders, but are rarely sufficient as sole therapy.17

The increasing number of diagnoses of bipolar affective disorder in children has been controversial,18 and we found that an unexpectedly high number of retrievals were of children under 14 with this primary diagnosis. This may reflect confusion of the symptoms of bipolar affective disorder with the acute behavioural manifestations of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, conduct disorder, learning disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, and unipolar depressive disorders. Alternatively, it may reflect the context‐specific nature of mental health‐related retrievals of children from remote locations: a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder may be perceived as more acceptable for initiating aeromedical retrieval. The high number of bipolar affective disorder diagnoses among retrieved children nevertheless warrants further investigation.

The hospitalisation rates and harms associated with misuse of amphetamine‐type stimulants (included under F15 in ICD‐10) are increasing in rural and remote areas,6,19 but retrieval rates for people with F15‐related diagnoses accounted for only 15 mental health‐related retrievals, or 8% of substance misuse‐related specific diagnoses. Some amphetamine‐type stimulant users may have been diagnosed with multiple substance misuse (F19), the most frequent substance misuse‐related diagnosis, as multiple substance misuse and dependence is common in this group. Not unexpectedly, alcohol misuse (F10) was the second most frequent primary substance misuse‐related diagnosis. Although many rural and remote areas have drug and alcohol services, they are usually limited to outpatient services (eg, counselling), and often lack medical and psychiatric expertise and resources.20 Many patients in rural and remote areas must travel more than 60 minutes to reach acute general medical services, and those who need more intensive acute psychiatric or addiction care may be referred for aeromedical retrieval to obtain definitive care or to exclude other organic causes.

The prevalence rates of mental disorders in rural areas cannot be deduced from RFDS retrieval data, as the need for retrieval is related to acuity of presentation rather than to overall hospital admission rates for these conditions. Whether rates of substance misuse disorders, in particular, are different in metropolitan and remote locations is a difficult question21 that cannot be resolved by our study.

Retrievals of people with substance misuse disorders and their subsequent hospital outcomes should be further investigated. Aeromedical retrieval for managing acute exacerbations of such conditions seems a costly and ineffective approach; comparing hospital length of stay data associated with these retrievals with the costs of community‐based services in areas with high retrieval rates would be appropriate. Whether regional factors influence retrieval outcomes should also be examined, as local variances in population characteristics and densities could result in differences in retrieval diagnoses.

Limitations

The primary limitations were that only primary diagnoses were available, and that ICD‐10 diagnoses were not provided for 39.4% of retrievals; further, diagnoses were made by medical flight crew. Data for Tasmania were unavailable, and the RFDS undertakes only limited aeromedical retrievals in the Top End of the Northern Territory, where other organisations provide aeromedical services. As we only recorded the primary diagnostic reason for aeromedical retrievals and not the patient’s other conditions, we may have underestimated the burden of illness and complexity of the patients retrieved by the RFDS.

Conclusion

The RFDS provides extensive aeromedical support for patients suffering mental and behavioural disorders, including many retrievals for treating the effects of psychoactive substance misuse; many were associated with multiple drug and alcohol misuse in people under the age of 19. The availability of RFDS and non‐RFDS mental health clinical support is lower in most of the retrieval communities than in major cities. In the absence of access to local dedicated mental health support and intervention services, many patients seek clinical assistance only when in crisis.

Box 1 – Demographic characteristics of patients with mental health problems transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, 2014–15 to 2016–17

|

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

Total |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients transported |

309 |

910 |

1038 |

2257 |

|||||||||||

|

Proportion of all retrievals |

2.7% |

3.0% |

3.6% |

3.2% |

|||||||||||

|

Age (years), mean (SD) |

38.8 (19.9) |

36.6 (20.8) |

34.7 (16.0) |

37.0 (19.3) |

|||||||||||

|

Sex (male) |

200 (65%) |

562 (62%) |

603 (58%) |

1365 (61%) |

|||||||||||

|

Indigenous Australians |

106 (34%) |

303 (33%) |

384 (37%) |

793 (35%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

SD = standard deviation. ◆ |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Age distribution of patients with mental health problems transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, 2014–15 to 2016–17*

* Missing data: 65 retrievals. ◆

Box 3 – International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth revision (ICD‐10) diagnoses for patients with mental health problems transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, 2014–15 to 2016–17

|

ICD‐10 diagnoses |

Number (proportion of ICD‐10 diagnoses) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F01–09) |

74 (5.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F03 Unspecified dementia |

25 (1.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F05 Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances |

20 (1.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F09 Unspecified organic or symptomatic mental disorder |

15 (1.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

14 (1.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–19) |

194 (14.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F10 … due to use of alcohol |

61 (4.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F12 … due to use of cannabinoids |

25 (1.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F15 … due to use of other stimulants, including caffeine |

15 (1.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F19 … due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances |

85 (6.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

8 (0.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20–29) |

522 (38.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F20 Schizophrenia |

227 (16.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F22 Persistent delusional disorders |

33 (2.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F23 Acute and transient psychotic disorders |

99 (7.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F25 Schizoaffective disorders |

23 (1.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F29 Unspecified nonorganic psychosis |

119 (8.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

21 (1.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Mood (affective) disorders (F30–39) |

409 (30.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F31 Bipolar affective disorder |

185 (13.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F32 Depressive episode |

153 (11.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F33 Recurrent depressive disorder |

26 (1.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F39 Unspecified mood [affective] disorder |

29 (2.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

16 (1.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other diagnoses |

168 (12.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F43 Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders |

33 (2.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F60 Specific personality disorders |

15 (1.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F91 Conduct disorders |

24 (1.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F99 Unspecified mental disorder |

48 (3.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

48 (3.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Total number of retrieval patients with ICD‐10 diagnoses |

1367 [60.6%] |

||||||||||||||

|

Number of retrieval patients without ICD‐10 diagnoses |

890 [39.4%] |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Age distribution of 194 patients with psychoactive substance use problems transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, 2014–15 to 2016–17

Box 5 – International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth revision (ICD‐10) diagnoses for younger patients with mental health problems transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service, 2014–15 to 2016–17, by age group

|

ICD‐10 diagnoses |

Number (proportion of ICD‐10 diagnoses) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Patients aged 0–14 years |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–19) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F10 … due to use of alcohol |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20–29) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F29 Unspecified nonorganic psychosis |

3 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

3 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Mood (affective) disorders (F30–39) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F31 Bipolar affective disorder) |

73 (74%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F32 Depressive episode |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F39 Unspecified mood (affective) disorder |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Other diagnoses |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F50 Eating disorders |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F99 Unspecified mental disorder |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

7 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Total number of retrieval patients with ICD‐10 diagnoses |

98 [79%] |

||||||||||||||

|

Number of retrieval patients without ICD‐10 diagnosis |

26 [21%] |

||||||||||||||

|

Patients aged 15–24 years |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–19) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F10 … due to use of alcohol |

22 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F12 … due to use of cannabinoids |

11 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F19 … due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances |

36 (12%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

6 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20–29) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F20 Schizophrenia |

48 (16%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F23 Acute and transient psychotic disorders |

21 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F29 Unspecified nonorganic psychosis |

39 (13%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

11 (3.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Mood (affective) disorders (F30–39) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F31 Bipolar affective disorder |

12 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F32 Depressive episode |

37 (12%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F33 Recurrent depressive disorder |

5 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F39 Unspecified mood (affective) disorder |

5 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

2 (0.65%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other diagnoses |

|

||||||||||||||

|

F43 Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders |

16 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F50 Eating disorders |

5 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F60 Specific personality disorders |

5 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F91 Conduct disorders |

6 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F99 Unspecified mental disorder |

9 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

14 (4.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Total number of retrieval patients with ICD‐10 diagnoses |

310 [61.8%] |

||||||||||||||

|

Number of retrieval patients without ICD‐10 diagnosis |

192 [38.2%] |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Received 12 November 2018, accepted 19 April 2019

- Fergus W Gardiner1

- Mathew Coleman2

- Narcissus Teoh3

- Abby Harwood4

- Neil T Coffee5

- Lauren Gale1

- Lara Bishop1

- Martin Laverty1

- 1 Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia, Canberra, ACT

- 2 UWA Medical School, the University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 3 College of Health and Medicine, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

- 4 Royal Flying Doctor Service, Queensland Section, Cairns, QLD

- 5 Centre for Research and Action in Public Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT

We thank the employees and supporters of the RFDS who made this research possible. We also acknowledge the RFDS sections and operations throughout Australia for their contributions to this study.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Bryant L, Garnham B, Tedmanson D. Tele‐social work and mental health in rural and remote communities in Australia. International Social Work 2018; 61: 143–155.

- 2. Bishop L, Ransom A, Laverty M. Health care access, mental health, and preventive health: health priority survey findings for people in the bush. Canberra: Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia, 2017. https://www.flyingdoctor.org.au/assets/documents/RN032_Healths_Needs_Survey_Result_P1.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 3. Hazell T, Dalton H, Caton T, Perins D. Rural suicide and its prevention: a CRRMH position paper. Newcastle: Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health, University of Newcastle, 2017. https://www.crrmh.com.au/content/uploads/RuralSuicidePreventionPaper_2017_WEB_FINAL.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 4. Caldwell TM, Jorm AF, Dear KB. Suicide and mental health in rural, remote and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med J Aust 2004; 18 (7 Suppl): S10–S14. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2004/181/7/suicide-and-mental-health-rural-remote-and-metropolitan-areas-australia.

- 5. Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. National amphetamine‐type stimulant strategy 2008–2011. Sept 2008. http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/ATS-strategy-08 (viewed June 2019).

- 6. Monahan C, Coleman M. Ice in the Outback: the epidemiology of amphetamine‐type stimulant‐related hospital admissions and presentations to the emergency department in Hedland, Western Australia. Australas Psychiatry 2018; 26: 417–421.

- 7. Buykx P, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Pashen D. Systematic review of effective retention incentives for health workers in rural and remote areas: towards evidence‐based policy. Aust J Rural Health 2010; 18: 102–109.

- 8. Humphreys J, Wakerman J. Primary health care in rural and remote Australia: achieving equity of access and outcomes through national reform: a discussion paper. 2009. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/44ee/5d28eb11f289ef0f48b15a64a3e4ef2e384f.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 9. Rural Health West. Rural and remote primary health care workforce planning: what is the evidence? Dec 2014. http://www.ruralhealthwest.com.au/docs/default-source/marketing/publications/d14-57147-rural-and-remote-primary-health-care-workforce-planning---what-is-the-evidence-may-16.pdf?sfvrsn=4 (viewed June 2019).

- 10. Smith T. We can and do make a difference by improving medical radiation services in rural and remote locations. J Med Radiat Sci 2017; 64: 241–243.

- 11. Gardiner FW, Gale L, Ransom A, Laverty M. Looking ahead: responding to the health needs of country Australians in 2028. The centenary year of the RFDS. Canberra: Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia, 2018. https://www.flyingdoctor.org.au/assets/documents/RN064_Looking_Ahead_Report_D3.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 12. Australian Department of Health. Australia's future health workforce: psychiatry. Mar 2016. https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/597F2D320AF16FDBCA257F7C0080667F/$File/AFHW%20Psychiatry%20Report.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 13. Bishop L, Ransom A, Laverty M, Gale L. Mental health in remote and rural communities. Canberra: Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia, 2017. https://www.flyingdoctor.org.au/assets/documents/RN031_Mental_Health_D5.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1270.055.005. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): volume 5. Remoteness structure, July 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.005 (viewed May 2019).

- 15. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Accredited training options. https://www.racgp.org.au/education/gps/gpmhsc/gp-mental-health-training-and-education (viewed May 2019).

- 16. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antipsychotic medicines dispensing 18–64 years. In: The first Australian atlas of healthcare variation. Canberra: ACSQHC, 2015. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/SAQ201_05_Chapter4_v8_FILM_tagged_merged-4-8.pdf (viewed June 2019).

- 17. Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016; 50: 410–472.

- 18. Parens E, Johnston J. Controversies concerning the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2010; 4: 9.

- 19. Dunn M, Henshaw R. Exploring the use of drug trend data in the regional alcohol and other drug workforce. Aust J Rural Health 2018; 26: 93–97.

- 20. Munro A, Shakeshaft A, Breen C, et al. Understanding remote Aboriginal drug and alcohol residential rehabilitation clients: who attends, who leaves and who stays? Drug Alcohol Rev 2018; 37 (Suppl 1): S404–S414.

- 21. Nietert PJ, French MT, Kirchner J, et al. Health services utilization and cost for at‐risk drinkers: rural and urban comparisons. J Stud Alcohol 2004; 65: 353–362.

Abstract

Objectives: To characterise the people retrieved by the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) for treatment of mental and behavioural disorders, and to assess mental health care provision in rural and remote areas.

Design: Prospective review of routinely collected RFDS and Health Direct data.

Setting, participants: RFDS aeromedical retrievals of patients from anywhere in Australia except Tasmania during 1 July 2014 – 30 June 2017 for the treatment of mental or behavioural disorders.

Main outcome measures: Retrievals by ICD‐10 mental and behavioural disorder diagnoses.

Results: 2257 patients were retrieved by the RFDS for treatment of mental or behavioural disorders, including 1394 males (62%) and 863 females (38%); 60% of patients were under 40 years of age, 35% identified as Indigenous Australians. The most frequent mental and behavioural disorders were schizophrenia (227 retrievals, 16.5% of retrievals with ICD diagnoses), bipolar affective disorder (185, 13.5%), and depressive episodes (153, 11.2%). Psychoactive substance misuse triggered 194 retrievals (14.2%), including misuse of multiple drugs (85, 6.2%), alcohol (61, 4.5%), and cannabinoids (25, 1.8%). The mean age of patients retrieved for treatment of substance misuse (29.6 years; SD, 11.6 years) was lower than for retrieved patients overall (37.0 years; SD, 19.3 years); 38 of 194 patients retrieved after psychoactive substance misuse (19.6%) were under 19 years of age. Most retrieval sites were rural and remote communities with low levels of mental health care support.

Conclusion: Mental and behavioural disorders are an important problem in rural and remote communities, and acute presentations trigger a considerable number of RFDS retrievals.