Abstract

Objectives: To determine the mean, median and 10th and 90th percentile levels of fees and out-of-pocket costs to the patient for an initial consultation with a consultant physician; to determine any differences in fees and bulk-billing rates between specialties and between states and territories.

Design, participants and setting: Analysis of 2015 Medicare claims data for an initial outpatient appointment with a consultant physician (Item 110) in 11 medical specialties representative of common adult non-surgical medical care (cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, geriatric medicine, haematology, immunology/allergy, medical oncology, nephrology, neurology, respiratory medicine and rheumatology).

Main outcome measures: Mean, median, 10th and 90th percentile levels for consultant physician fees and out-of-pocket costs, by medical specialty and state or territory; bulk-billing rate, by medical specialty and state/territory.

Results: Bulk-billing rates varied between specialties, with only haematology and medical oncology bulk-billing more than half of initial consultations. Bulk-billing rates also varied between states and territories, with rates in the Northern Territory (76%) nearly double those elsewhere. Most private consultations require a significant out-of-pocket payment by the patient, and these payments varied more than fivefold in some specialties.

Conclusion: Without data on quality of care in private outpatient services, the rationale for the marked variations in fees within specialties is unknown. As insurers are prohibited from providing cover for the costs of outpatient care, the impact of out-of-pocket payments on access to private specialist care is unknown.

The known Concerns have been expressed about high consultation fees and the potential for a two-tiered health system developing in Australia. Insurers are prohibited from covering outpatient physician consultation charges.

The new There were wide variations in bulk-billing rates and fees within specialties, between specialties, and between states and territories. Out-of-pocket payments by patients varied more than fivefold in some specialties.

The implications There is a lack of transparency and public availability of information about charges for outpatient consultations. Without data on quality of care, the justifiability of the differences in fees cannot be determined.

About 2.4 million initial consultations with consultant physicians are conducted in Australia each year.1 The Medicare program provides a set payment (rebate) for specific clinically relevant services to offset the cost to patients of private consultations.2 This payment is based on the “schedule fee”, the amount determined by the Department of Health as being reasonable, on average, for the service provided.2 The schedule fee for each eligible service is published in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Each year, Medicare provides about $300 million in rebates for initial appointments with consultant physicians, accounting for about 1.5% of total Medicare benefits.3

The schedule fee is stated to reflect the difficulty and time involved in providing the service, as well as factors such as major capital costs, and direct (eg, consumables) and indirect costs (eg, salaries for administrative staff).4 Medicare provides a rebate to patients of 85% of the schedule fee for most outpatient appointments.2 Doctors may choose to accept the 85% benefit amount as the full payment; this is known as bulk-billing and results in there being no cost to the patient.2 About 41% of medical and surgical outpatient specialist or consultant attendances were bulk-billed during the September quarter of 2016.5 “Specialist” and “consultant physician” are Medicare terms used in item descriptions, and refer to medical practitioners recognised as either specialists or consultant physicians for the purposes of the Health Insurance Act 1973.

Doctors have expressed concern that increases in fee levels in the MBS have not kept pace with inflation and do not reflect appropriate payments for services.6-8 Specialists and consultants in private practice are permitted to charge more than the schedule fee,9 and can charge any rate they feel the market will bear.10 MBS data show that 56.1% of outpatient specialist and consultant physician appointments are charged at rates higher than the schedule fee.5

Since 1983, legislation has prohibited private health insurers from covering outpatient visits.11,12 The patient is therefore responsible for paying any difference between the fee charged by the doctor and the Medicare rebate for any non-bulk-billed service. This difference, the out-of-pocket expense or gap fee, is usually paid by the patient at the time of service delivery.10 There is a large degree of variation in fees charged by specialists and consultant physicians across geographic areas,5 as well as between specialties.

In 2009–10, Australian households spent an average of $325 annually on out-of-pocket expenses for specialist and consultant physician consultations.13 The amount varied considerably between states; it was lowest in Tasmania ($125 per household) and highest in the Australian Capital Territory ($554 per household).13 A study during 2013–14 found that 7.9% of people who needed to see a specialist or consultant physician delayed the appointment or did not go at all because of the expense.14 This economic barrier to access is more important for people living in areas of socio-economic disadvantage or outside capital cities, as well as for those with long term health problems.15

Concerns about the high levels of medical appointment fees and the limited ability of many Australians to pay for care have recently been raised in the media and by professional groups (including the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons).15 A report by a private health insurance company identified marked variation in fees for inpatient procedures, with some surgeons charging almost $17 000 more than other surgeons for a particular operation.16 As private health insurers are prohibited from reimbursing outpatient consultation fees, there are no data for such services according to specialty, reducing the transparency of charging practices.

Publicly available data indicate that the average out-of-pocket charge for private outpatient medical specialist or consultant physician appointments is $71.90.5 However, fee differences between medical specialties and between states/territories have not been examined.

As waiting times for public specialty care have increased in Australia, the number of patients seeking care in the private sector has also increased. Greater transparency in consultation charges, particularly regarding differences between states and specialties, would benefit patients and provide information about the actual costs to the patient of private outpatient care. Our study examined the actual fees charged for an initial outpatient consultation (Medicare item number 110) by consultant physicians in different specialties, and calculated the out-of-pocket costs for these services. The schedule fee (January 2016) for an initial appointment with a consultant physician was $150.90 and the benefit (rebate) amount was $128.30.2

Methods

We analysed aggregated, non-identifiable Medicare data from the Commonwealth Department of Human Services (DHS) on Medicare claims for item number 110 (an initial appointment with a consultant physician following a referral2) rendered between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2015. The data file was reviewed by the Department of Health before it was released to us. To prevent specific providers being identified, the DHS suppressed data when fewer than 20 services were provided in a specific specialty in a state or territory.

The data provided by the DHS included the number of initial outpatient medical consultations (Medicare item number 110) for which a claim for benefit was made. These included separate data for the absolute number of bulk-billed and non-bulk-billed visits. Whenever a Medicare claim is made for a non-bulk-billed service, the actual charge for the visit must be provided to the DHS as part of the claim. The DHS data included the mean, median, and 10th and 90th percentile levels of actual charges by doctors. These data were aggregated by medical specialty and state or territory of the doctor providing the service.

We analysed data from 11 medical specialties representative of non-surgical medical care provided to adults by consultant physicians: cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, geriatric medicine, haematology, immunology/allergy, medical oncology, nephrology, neurology, respiratory medicine, and rheumatology. We report only consultation charges for non-bulk-billed visits.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, 1646466.1).

Results

Proportion of consultations bulk-billed, by specialty and state

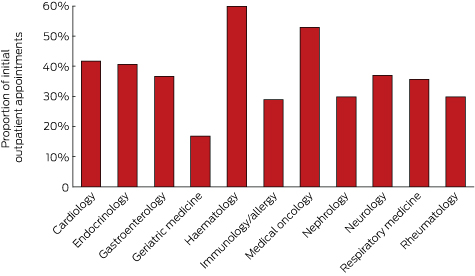

The specialties with the highest proportion of bulk-billed initial consultations (Medicare item 110) were haematology and medical oncology. The lowest bulk-billing rates were in geriatric medicine. Most specialties bulk-billed 30–42% of visits (Box 1).

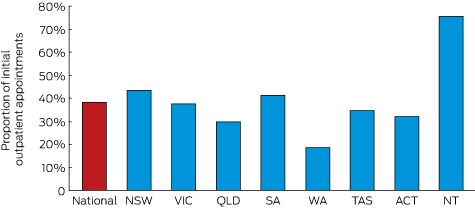

The state or territory with the highest overall bulk-billing rate was the Northern Territory (76% of visits); New South Wales and South Australia also had bulk-billing rates above 40%. Only Western Australia had a bulk-billing rate under 20% (Box 2).

Fees for initial outpatient consultation: by specialty

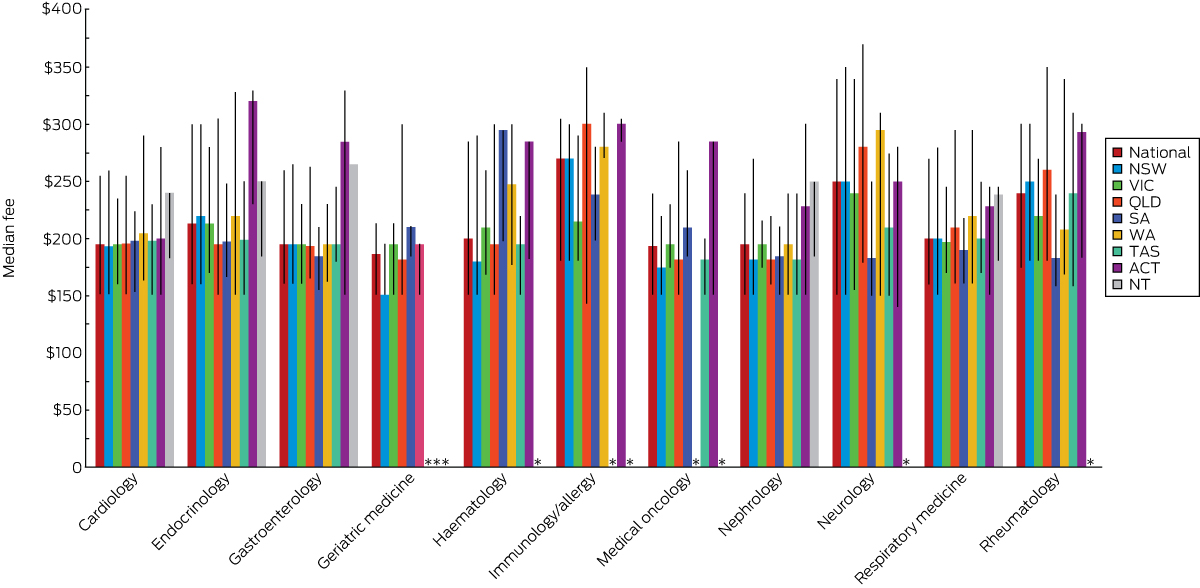

There was marked variation within and between specialties, as well as between states and territories, in the mean, median and 10th/90th percentile levels of fees for an initial outpatient consultation with a consultant physician.

Immunology/allergy was the specialty with the highest mean ($257) and median ($270) fees for an initial consultation, followed by neurology (mean, $252; median, $250). Mean fees for an initial consultation were less than $200 in only three of the 11 specialties (medical oncology, nephrology and geriatric medicine), with the lowest mean in geriatric medicine (Box 3).

There were four specialties for which the 90th percentile fee level was at least $300 for an initial consultation: neurology ($340), immunology/allergy ($305), rheumatology ($300), and endocrinology ($300). The 10th percentile fee level for nine specialties was $160 or less; the exceptions were immunology/allergy ($180) and rheumatology ($175).

The highest median out-of-pocket cost was for an initial consultation for immunology/allergy ($141.70), and the lowest was for geriatric medicine ($58.30; Box 3).

Variation in fees and out-of-pocket costs within specialties

There were also marked differences within specialties in the range of fees for an initial consultation. On average, the 90th percentile fee was 73% higher than that at the 10th percentile. The specialty with the greatest difference between the 10th and 90th percentile fee levels was neurology, where the difference between the upper and lower decile fees ($189) was equivalent to a 125% difference in fee; the narrowest range was the $62.50 difference (15%) for geriatric medicine. The 90th percentile out-of-pocket cost was more than 400% higher than the 10th percentile level for many specialties (Box 3).

Fees for initial outpatient consultation: by state and territory

Box 4 shows the variation in median fee for each specialty by state. The highest median fees for five of the 11 specialties were charged in the ACT, for three in the NT. Neither Victoria nor NSW had the highest median fees for any of the specialties.

Discussion

Our most important finding is the wide range of fees charged within specialties for an initial physician outpatient consultation. There is also variation within and between states. As there is no publicly available information about the quality of care in the outpatient setting or any validated outpatient quality measures, these fee variations are not based on any objective information about the care provided by individual doctors. Further, because information on the range of fees for outpatient consultations was not previously available, patients have not been aware that their out-of-pocket payments could vary markedly according to the private consultant physician they visit.

Because of increasing waiting times in the public sector,17,18 many patients choose private care so that they can see a specialist sooner. However, our data indicate that only a minority of these visits are bulk-billed, with the notable exceptions of consultations in haematology and medical oncology. Most patients must therefore make out-of-pocket payments to receive care in the private system. In contrast to inpatient care and many procedures, private health insurance coverage is not available for outpatient consultations, as private health insurance funds have been prohibited by law since 1983 from covering any difference between the schedule fee and the practitioner’s actual fee for outpatient visits.11 The rationale for this prohibition was the belief that allowing private health insurers to subsidise out-of-pocket costs might encourage practitioners to raise their fees further above the schedule fee, reducing access to specialist care for people who could not afford to either purchase private health insurance or to directly pay the higher fees.12 A reform was proposed to Parliament in 2003 that would have allowed private health insurers to cover outpatient costs that exceeded a $1000 annual threshold,11 but was not adopted.

The reasons for the variation in bulk-billing rates between states are not clear, with the exception of the relatively lower economic status of the population of the NT. There may be other economic factors affecting billing patterns in different states. Studies in other countries have found variations in the cultural norms of charging patterns of physicians in different communities.19 This phenomenon deserves further investigation.

Although the Medicare fee schedule was designed to be adjusted for inflation, there have been years in which no adjustment was made.7 This was usually the result of efforts to achieve federal budget savings, as increases in schedule fees would result in higher Medicare rebates and therefore higher government health care expenditure. However, one potential consequence of failing to increase schedule fees has been that doctors raise their own fees to keep pace with inflation and to increase their income.7 Over time, the gap between charged fees and the level of the rebate has grown, resulting in rising out-of-pocket charges.

For patients, limited funding of the public sector has resulted in longer waiting times for public outpatient consultations, leading to increased pressure to seek private care.18 Patients with limited means are faced with a difficult choice between delays for care in the public sector and out-of-pocket expenses in the private sector. There is consequently a risk that a two-tiered system of health care for outpatient consultations will develop.

It is unclear why the median and 90th percentile fees for immunology/allergy and neurology consultations are higher than for other initial outpatient consultant physician consultations. The duration of training for these specialties is no longer than for the other specialties we examined. It is important to note that the fee data in our report are for the same Medicare item number; the scheduled fee for item 110 is fixed, regardless of the duration of the consultation, and does not include any payment for a procedure, which must be billed separately when claiming a rebate. Some physicians may provide longer consultations than others, and this may explain some of the variance in fees within and between different specialties. As Medicare does not collect information on the duration of visits, data are not available for assessing this hypothesis.

There is also no clear rationale for the variation in median fees between states and territories. High fees for many consultant physician specialties in the ACT may reflect the economic status of the region or that of the patient population. Our findings for the NT might appear paradoxical: the bulk-billing rate in the NT was the highest in Australia, but some of the highest median fees were also charged here. It is possible that doctors in the NT bulk-bill the large number of patients with limited incomes, but, to compensate for the perceived reduction in income, charge those with the ability to pay much higher fees. Around the country, it is possible that some of the variation in fees is the result of physicians charging different patients different fees,20 but additional data would be required to determine the magnitude of this practice.

The lack of publicly available data about the range of fees for specific services places patients at a distinct disadvantage when seeking affordable medical care. Further, as there are no data on quality of care in the outpatient setting, patients are not only unsure about the range of appropriate fees, but also about the value of the service they receive. There are currently no requirements for private consultants to participate in quality assessments of their outpatient care, so patients cannot assess the association, if any, between fee level and quality of care. Other nations have developed programs for assessing the quality of outpatient care and make this information available to patients.21 Efforts of this type are needed in Australia as the health care system matures. Greater transparency in the fees charged by consultant physicians may have an impact that would benefit patients.

In light of our data, and the failure of increases in the MBS fee schedule to keep pace with inflation, the policy of prohibiting insurance coverage for outpatient care may need to be reconsidered. It appears that the goal of this policy — to limit outpatient fees — has met with limited success at best. The accessibility of private outpatient care for Australians is currently compromised by the level of out-of-pocket expense. Although private insurance has enabled many Australians to use private inpatient care, this has not been the case for outpatient consultations. It is possible that expanding insurance coverage to outpatient care would lead to a further increase in consultant fees. The primary goal of any changes in policy should be to improve access to consultants, whether in the public or private sectors. Additional research is essential for better understanding the variation in fees charged by consultant physicians and for informing future policies.

Box 1 – Proportion of initial outpatient appointments with a consultant physician (Medicare item 110) in 2015 that were bulk-billed, by specialty

Box 2 – Proportion of initial outpatient appointments with a consultant physician (Medicare item 110) in 2015 that were bulk-billed, by state and territory

Box 3 – Consultation fees and patient’s out-of-pocket costs for initial non-bulk-billed outpatient appointment with a consultant physician, 2015

Specialty |

Fee |

Out-of-pocket costs |

|||||||||||||

Mean |

Median |

10th percentile |

90th percentile |

Mean |

Median |

10th percentile |

90th percentile |

||||||||

Cardiology |

$202.00 |

$195.20 |

$150.90 |

$255.00 |

$73.70 |

$66.90 |

$22.60 |

$126.70 |

|||||||

Endocrinology |

$223.00 |

$213.40 |

$160.00 |

$300.00 |

$94.70 |

$85.10 |

$31.70 |

$171.70 |

|||||||

Gastroenterology |

$204.00 |

$195.20 |

$160.00 |

$260.00 |

$75.70 |

$66.90 |

$31.70 |

$131.70 |

|||||||

Geriatric medicine |

$185.00 |

$186.60 |

$150.90 |

$213.40 |

$56.70 |

$58.30 |

$22.60 |

$85.10 |

|||||||

Haematology |

$214.00 |

$200.00 |

$150.90 |

$285.00 |

$85.70 |

$71.70 |

$22.60 |

$156.70 |

|||||||

Immunology/allergy |

$257.00 |

$270.00 |

$180.00 |

$305.00 |

$128.70 |

$141.70 |

$51.70 |

$176.70 |

|||||||

Medical oncology |

$196.00 |

$193.85 |

$150.90 |

$240.00 |

$67.70 |

$65.55 |

$22.60 |

$111.70 |

|||||||

Nephrology |

$196.00 |

$195.00 |

$150.90 |

$240.00 |

$67.70 |

$66.70 |

$22.60 |

$111.70 |

|||||||

Neurology |

$252.00 |

$250.00 |

$151.00 |

$340.00 |

$123.70 |

$121.70 |

$22.70 |

$211.70 |

|||||||

Respiratory medicine |

$211.00 |

$200.00 |

$160.00 |

$270.00 |

$82.70 |

$71.70 |

$31.70 |

$141.70 |

|||||||

Rheumatology |

$236.00 |

$240.00 |

$175.00 |

$300.00 |

$107.70 |

$111.70 |

$46.70 |

$171.70 |

|||||||

Received 1 June 2016, accepted 8 September 2016

- Gary L Freed1

- Amy R Allen2

- 1 Centre for Health Policy, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Australian Government, Department of Human Services. All Medicare items in “Group: A4 Consultant Physician (other than Psychiatry)” processed from December 2015 to November 2016 [website]. Updated Dec 2016. http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/do.jsp?_PROGRAM=/statistics/mbs_item_standard_report&VAR=services&STAT=count&PTYPE=month&START_DT=201512&END_DT=201611&RPT_FMT=by+state&DRILL=ag&GROUP=A0401 (accessed Dec 2016).

- 2. Australian Government, Department of Health. Medicare benefits schedule book: operating from 01 January 2016. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Downloads-201601 (accessed Aug 2016).

- 3. Australian Government, Department of Health. Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) review taskforce. Data, expenditure, patterns/drivers of growth [MBS Review Taskforce Meeting 1–3 July 2015, agenda item 5.2]. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/814102E8BAB00FE8CA257F0E001D17BF/$File/Document 2 FOI 051-1516 for publication.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 4. Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Frequently asked questions about Medicare, the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the Medicare Benefits Schedule listing process. Canberra: Consumers Health Forum of Australia, 2013. http://web.archive.org/web/20160311230215/https://chf.org.au/fac-freq-asked-questions-MBS.chf (archived version) (accessed May 2016).

- 5. Australian Government, Department of Health. Quarterly Medicare statistics. Updated Nov 2016. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Quarterly-Medicare-Statistics (accessed Dec 2016).

- 6. Australian Medical Association. Medicare undermined as rebates kept in deep freeze [media release] 20 July 2015. https://ama.com.au/media/medicare-undermined-rebates-kept-deep-freeze (accessed May 2016).

- 7. Australian Medical Association. AMA President Prof Brian Owler: Federal budget 2016, Medicare freeze [radio interview transcript]. 5 May 2016. https://ama.com.au/media/ama-transcript-medicare-rebate-freeze (accessed May 2016).

- 8. Hoffman T. Freeze will cost GPs $50,000 in 2019. Australian Doctor [online] 2016; 4 May. http://www.australiandoctor.com.au/news/latest-news/exclusive-freeze-will-cost-gps-$50-000-in-2019 (accessed May 2016).

- 9. O’Sullivan BG, Joyce CM, McGrail MR. Adoption, implementation and prioritization of specialist outreach policy in Australia: a national perspective. Bull World Health Org 2014; 92: 512-519.

- 10. Cheng TC, Scott A, Jeon SH, et al. What factors influence the earnings of general practitioners and medical specialists? Evidence from the Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life survey. Health Econ 2012; 21: 1300-1317.

- 11. Colombo F, Tapay N. Private health insurance in Australia: a case study (OECD health working papers, No. 8). Paris: OECD Publishing, 2003. http://www.oecd.org/australia/22364106.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 12. Elliot A, Hancock N. Health Legislation Amendment (Medicare and Private Health Insurance) Bill 2003 (Bills digest No. 176, 2002–03). Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003. http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd0203/03bd176 (accessed May 2006).

- 13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6530.0. Household expenditure survey, Australia: summary of results, 2009–10. Sept 2011. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6530.02009-10?OpenDocument (accessed May 2016).

- 14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4839.0. Patient experiences in Australia: summary of findings, 2013–14. Nov 2014. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4839.02013-14?OpenDocument (accessed May 2016).

- 15. Russell L. Too high: specialist fees hit the sickest patients. Sydney Morning Herald 2015; 24 Nov. http://www.smh.com.au/comment/too-high-specialist-fees-hit-the-sickest-patients-20151124-gl6ess.html (accessed May 2016).

- 16. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Medibank. Surgical variance report: general surgery. Melbourne: RACGP, 2016. https://www.surgeons.org/media/24091469/Surgical-Variance-Report-General-Surgery.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 17. State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services. Specialist clinics activity and wait time report: March quarter 2015–16: preliminary. Melbourne: State of Victoria, 2016. http://performance.health.vic.gov.au/Renderers/ShowMedia.ashx?id=98021730-9444-4a8c-952c-1e3549042913 (accessed May 2016).

- 18. Medew J. Victorians waiting more than four years to see a public hospital specialist. The Age (Melbourne) 2016; 1 Feb. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/victorians-waiting-more-than-four-years-to-see-a-public-hospital-specialist-20160201-gmiyr2.html (accessed May 2016).

- 19. Margolis PA, Cook RL, Earp JA, et al. Factors associated with pediatricians’ participation in Medicaid in North Carolina. JAMA 1992; 267: 1942-1946.

- 20. Johar M, Mu C, Van Gool K, Wong CY. Bleeding hearts, profiteers, or both: specialist physician fees in an unregulated market. Health Econ 2016; doi: 10.1002/hec.3317 [Epub ahead of print].

- 21. Department of Health and Human Services (USA). Quality payment program [website]. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Quality-Payment-Program.html (accessed Aug 2016).

Gordon Robert WyndhamDavies

What has happened is that over many years, quite apart from the recent reimbursement freeze, the government has eroded the original schedule and that in the original terms the currently charged fees should be considered as the basis for a redetermination of the most common fee. Differences will always arise reflecting experience and seniority (and hopefully competence) of practitioners but these are likely to be less if the rebatable quantum is set at a level which reflects current real world practice.

It should also be noted that the AMA historically has opposed gap insurance on the basis that that there should be a cost signal to most patients although this is accompanied by an understanding that practitioners would exercise their discretion not to charge the gap for those in financial difficulty.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Assoc Prof Gordon Robert WyndhamDavies

University of Wollongong

Peter Smerdely

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Prof Peter Smerdely

St George Hospital, Sydney

john Raven

Freed and Allen for their research paper used Item No 110 for which the Medicare Rebate since 1/11/12 has been $123.80. Since 1/11/07 in my practice as a Consultant Physician in the specialty of Clinical Haematology, I have used Item No 132 for which the Medicare Rebate since 1/11/12 has been $224.35. The same Item No has been used by other Consultant Physicians including general physicians, oncologists, immunologists, rheumatologists, neurologists and others. On only rare occasions have I used Item No 110. I shall be interested to see the next paper by Freed and Allen when they have revised their figures to include all the fees charged by Consultant Physicians for their 1st Consultations.

The introduction of Item Nos 132 and 133 by the Commonwealth Government on 1/11/07 was an intelligent act of magnanimity for which one also has to thank the Association of Consultant Physicians and the AMA. I might have thought that practices such as mine in suburban and rural areas would not have survived these last 10 years without the increase in fees. The newspaper article in the West Australian expressed worry about a fall in bulk billing rate.For those who may not know it, the Medicare Rebate for the Consultant Physician's ordinary follow-up consultation (No 116) since 1/11/12 has been $64.20.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr john Raven

Dr J L Raven