An innovative model for the delivery of child and family services

The Central Australian Aboriginal Congress is a large Aboriginal community-controlled health service based in Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. Since the 1970s, Congress has developed a comprehensive model of primary health care delivering evidence-based services on a foundation of cultural appropriateness.

In recent years, the community-elected Congress Board has focused on improving the developmental outcomes of Aboriginal children. This has led to the development of an innovative model for the delivery of child and family services, based on the belief that the best way to “close the gap” is to make sure it is not created in the first place.

Early childhood development

It is well established that social and environmental influences in early childhood shape health and wellbeing outcomes across the life course. Adverse childhood experiences are correlated with a wide range of physical health problems and with increased levels of depression, suicide attempts, sexually transmitted infections, smoking and alcoholism.1

The pathways for these effects are complex; however, we know that during the first few years of life, the interactions between genetics, environment and experience have a dramatic impact on brain development. During this critical period, children need stimulation and positive relationships with caregivers to develop the neural systems crucial for adult functioning.2

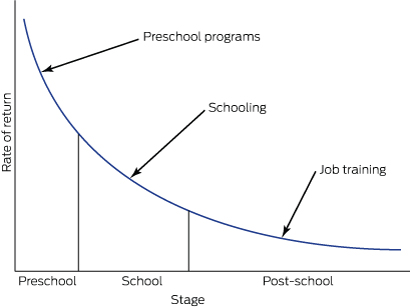

This evidence indicates that we should not wait to intervene until a child is ready for school at around 5 years of age. By this stage, children have passed many developmental gateways for language acquisition, self-regulation and cognitive function, and their developmental trajectories are set. Of course, developmentally challenged children must be provided with appropriate services during their school years and later in life, but such interventions require increasing amounts of resources (Box 1)3 and produce diminishing returns as the child gets older.4

Governments and policy makers have now widely recognised the importance of investing in the early years.5 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has advised that investing in early childhood is the most important measure that Australia can take to grow the economy and be competitive in the future.6

Successful programs

There are well evidenced programs for young children and their families that significantly improve health, educational and social outcomes throughout the life course, and which are highly cost-effective compared with later interventions (or with doing nothing, which is the most expensive option).

Congress has taken particular interest in two preventive programs that have been successfully implemented in disadvantaged communities overseas. These are the Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP) and the Abecedarian approach to educational day care. Both programs work with caregivers and children before developmental problems arise, providing children with the stimulation, quality relationships and access to the services they need for healthy development.

The NFP is a program of nurse home visitation which begins during pregnancy and continues until the child’s second birthday. Pioneered in the work of Olds and colleagues,7 trained nurses use a structured program to address personal and child health, quality of caregiving for the infant, maternal life course development and social support. Special attention is given to establishing a safe, nurturing and enriched parent–infant relationship. Over many years of working with low income, socially disadvantaged families in the United States, the NFP has achieved improvements in women’s prenatal health8 and reductions in child abuse and neglect, maternal use of welfare, substance misuse, and contact with the criminal justice system.9 Children who participated in the program showed long term benefits, such as reduced antisocial behaviour and substance misuse during young adulthood.10

The Abecedarian approach provides a centre-based preventive program for children who are at high risk of developmental delay. It has three main elements — learning games, conversational reading and enriched caregiving — with a priority on language acquisition. The approach has been rigorously evaluated, and longitudinal studies that followed children into adulthood found that participants did better at school; gained more years of education; had better employment outcomes;4 showed reduced rates of smoking, drug use and teen pregnancies and led a more active lifestyle.11 There is also evidence of a significantly lower prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic disease for participants (particularly men) when they reach their mid-30s.12 These effects work against the social gradient, with children from more disadvantaged environments benefitting the most,13 which makes the approach a potentially powerful contributor to social equity.

The situation in central Australia

While the cultures and histories of Aboriginal communities in central Australia make them unique, they share many characteristics with communities in which these programs have been effective.

In particular, many Aboriginal children in and around Alice Springs grow up in an environment marked by poverty, substance misuse and lack of responsive care, with low levels of formal education and school attendance coupled with economic marginalisation and social exclusion.

This is reflected in figures from the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC), which show that by the time they start school, 43% of Indigenous children in the Alice Springs region are vulnerable on two or more of five developmental domains. This is six times the rate for non-Indigenous children (7%) (NT AEDC Manager, Early Childhood Education and Care, NT Department of Education, personal communication, 1 April 2016).

Responding to the developmental needs of Aboriginal children

The Congress integrated model for child and family services is the culmination of its efforts to develop an innovative service response to these challenges based on the best available evidence (Box 2).The key elements of the model include nurse home visitation through the Australian Nursing Family Partnership Program (ANFPP); the Preschool Readiness Program (PRP); the Healthy Kids Clinic; family support services, such as Targeted Family Support and Intensive Family Support; and the Child Health Outreach Program. Congress also runs a childcare centre.

As part of this model, Congress has delivered two short-term programs drawing on the Abecedarian approach. The first was an intensive intervention run through the PRP in 2011 and 2012.14 In the second, Congress is collaborating with the University of Melbourne to assess the impact of a limited implementation of the Abecedarian approach with children attending the Congress childcare centre.

The importance of integration

The Congress model is founded on a long term population health approach that is expected to deliver results in health and wellbeing across the life course. Integration of services under a single provider is the key to achieving this potentially transformative change, enabling children and families to be referred seamlessly to the services that best meet their needs. Such integration is now recognised as a crucial reform needed to increase the cost-effectiveness of services and improve access and outcomes for children and their families.15

The advantages of the Congress integrated model are that:

it supports a consistent approach to screening, allowing children and families to be referred to the programs that best meet their needs;

it allows internal efficiencies between programs to enhance services, thus making a better use of available resources;

it is built on the existing relationships that Congress has with Aboriginal families in Alice Springs through the delivery of culturally appropriate primary health care;

it allows a common evidence-based approach, modified to meet the cultural and social needs of our clients;

it may provide secondary gains for other health programs (eg, working with client families on healthy lifestyles or addiction problems); and

it encourages partnerships with researchers to evaluate progress and with other service providers for follow-up of clients.

Promising early results

This integrated model for child and family services may take many years to show all its benefits. Nevertheless, the early signs are promising.

While maintaining engagement with any disadvantaged population is a challenge, the ANFPP shows a high level of client acceptance, largely due to the inclusion of Aboriginal community workers alongside the nurses. This is reflected in good retention rates: the attrition rate before the child reaches 1 year of age is 44.1%, lower than in the overseas implementations where it is 49.5%. Moreover, a preliminary analysis shows an infant mortality rate of 8.3 per 1000 live births for the 240 infants whose mothers have been on the Congress program, which compares favourably with the NT rate of 13.7 infant deaths per 1000 live births. While these small numbers must be interpreted with caution, they are consistent with the reductions in infant mortality demonstrated in randomised control trials in the US.16

The PRP, which incorporated the Abecedarian approach, also showed positive results even with a limited program delivery. This included developmental gains in expressive language and social skills,17 higher preschool attendance rates and improvements in confidence and school readiness.15

While the data from the collaboration between Congress and the University of Melbourne to implement the Abecedarian approach at the Congress childcare centre are not yet available for publication, an early analysis suggests that they will also show significant benefits in children’s language acquisition and attention.

Conclusions

The integrated model implemented by Congress is already yielding some important lessons on addressing early childhood development in Aboriginal Australia.

First, there is a need for an evidence-based approach adapted to local social and cultural conditions. This requires fidelity to the original program design allied with the local knowledge that Aboriginal community-controlled health services such as Congress have built up over the years. We contrast this approach of responsible innovation with reckless innovation, which ignores what has already been achieved and proceeds on the basis of little or no evidence.

Second, there are the benefits of integrated solutions before school age being provided through the primary health care sector where possible. It is this sector which, through its delivery of antenatal and perinatal care, establishes supportive relationships with mothers, families and children in the period from conception to 3 years of age. Thereafter, the education sector should continue to take responsibility for preschool and primary education.

Box 1 – Rates of return for human capital investment for disadvantaged children

Modified from Heckman and Masterov3

Box 2 – Central Australian Aboriginal Congress integrated model for child and family services

Description |

Primary prevention* |

Secondary prevention† |

|||||||||||||

Child focus |

Carer focus |

Child focus |

Carer focus |

||||||||||||

Centre based |

Most work is done at a centre where a child or families come in to access service |

Abecedarian educational day care; immunisations; child health checks; developmental screening |

Health advice to parents in clinic (eg, nutrition, brushing teeth, toilet training) |

Child-centred play therapy; therapeutic day care; Preschool Readiness Program; antibiotics |

Filial therapy; circle of security; parenting advice/programs; parent support groups |

||||||||||

Home visitation |

Most work is done in the homes of families where staff outreach to children and families |

Mobile play groups |

Nurse home visitation; families as first teachers (home visiting learning activities) |

Child Health Outreach Program; ear mopping |

Targeted Family Support; Intensive Family Support; case management models for children at risk; Parents under Pressure |

||||||||||

* The primary prevention targets children with no current problems, but who are at risk of developing them — the identified risk is usually based on low socio-economic status or maternal education level. † The secondary prevention targets children with current problems identified early in life when they are most likely to respond to intervention and before the problems get worse — it is determined by screening or referral to services. | |||||||||||||||

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Anda RF, Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and their relationship to adult well-being and disease: turning gold into lead. USA: The National Council webinar, 2012. http://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Natl-Council-Webinar-8-2012.pdf (accessed Mar 2016).

- 2. Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA. From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000.

- 3. Heckman JJ, Masterov DV. The productivity argument for investing in young children. University of Chicago, 2007 http://jenni.uchicago.edu/human-inequality/papers/Heckman_final_all_wp_2007-03-22c_jsb.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 4. Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Early learning and school readiness: can early intervention make a difference? Merrill-Palmer Q 2004; 50: 471-491.

- 5. Council of Australian Governments. Investing in the early years—a national early childhood development strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009 https://www.coag.gov.au/sites/default/files/national_ECD_strategy.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 6. Hutchens G. OECD: G20 commitment to boost GDP by 2 per cent in doubt. Sydney Morning Herald 2016, 26 February http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/oecd-g20-commitment-to-boost-gdp-by-2-per-cent-in-doubt-20160226-gn4ha6.html (accessed 5 May 2016).

- 7. Olds DL, Sadler L, Kitzman H. Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: recent evidence from randomized trials. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48: 355-391.

- 8. Olds DL, Henderson CR Jr, Tatelbaum R, Chamberlin R. Improving the delivery of prenatal care and outcomes of pregnancy: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics 1986; 77: 16-28.

- 9. Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR Jr, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA 1997; 278: 637-643.

- 10. Olds D, Henderson CR Jr, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280: 1238-1244.

- 11. Campbell FA, Wasik BH, Pungello E, et al. Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Child Res Q 2008; 23: 452-466.

- 12. Campbell F, Conti G, Heckman JJ, et al. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science 2014; 343: 1478-1485.

- 13. Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Prevention of intellectual disabilities: early interventions to improve cognitive development. Prev Med 1998; 27: 224-232.

- 14. Moss B, Silburn SR. Preschool Readiness Program: improving developmental outcomes of Aboriginal children in Alice Springs. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2012.

- 15. Forrest A. The Forrest Review. Creating parity. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014 https://indigenousjobsandtrainingreview.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/The_Forrest_Review.pdf (accessed May 2016).

- 16. Olds DL, Kitzman H, Knudtson MD, et al. Effect of home visiting by nurses on maternal and child mortality: results of a 2-decade follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168: 800-806.

- 17. Moss B, Harper H, Silburn SR. Strengthening Aboriginal child development in central Australia through a universal preschool readiness program. Australas J Early Child 2015; 40: 13-20.

We thank Patrick Cooper, former clinical psychologist at Central Australian Aboriginal Congress, for his work in developing the integrated model of child and family services outlined in this article.

No relevant disclosures.