Considerable media and public attention has been focused in recent years on the refusal by some parents to vaccinate their children as recommended by health authorities. Vaccination coverage has often been purported to be declining nationally as a result, particularly in more affluent inner-city suburbs (for example, 1).

Until the end of 2015, the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) recorded registered objection to vaccination based on personal, philosophical or religious beliefs. Registration of objection required a vaccination provider to complete a conscientious objection form; this was necessary only when the parents wished to remain eligible for family assistance payments from the federal government or, in some states, to be able to enrol their child in childcare. It is therefore likely that ACIR data have not captured all instances of parental objection to vaccination.

Only one published Australian study has reported an in-depth analysis of vaccination objections, a national survey conducted in 2001.2 Our study aimed to examine trends in registered vaccination objection and differences in the geographic and demographic distribution of objection across Australia, and to assess the contribution of unregistered objection to incomplete vaccination.

Methods

The ACIR was established in 1996 by incorporating demographic data recorded by Medicare for all enrolled children under the age of 7 years.3 Children not enrolled in Medicare can also be added to the ACIR with a supplementary number. “Fully vaccinated” status is assessed at three key milestones: 12 months of age (for vaccines due at 2, 4 or 6 months); 24 months of age (for vaccines due at 12 or 18 months); and 60 months of age (for vaccines due at 48 months). The algorithms used for calculation of fully vaccinated status at these milestones have been described previously.4 We defined “partially vaccinated” children as those with one or more vaccinations recorded, but who were not fully vaccinated with respect to the vaccines due at the relevant schedule points.

We examined the following four subgroups of children, defined according to ACIR data:

objection to vaccination and no vaccinations recorded;

objection to vaccination and one or more vaccinations recorded;

no objection to vaccination and no vaccinations recorded; and

no objection to vaccination and partially vaccinated.

We examined trends over time for cohorts aged 12 months to less than 7 years for the period 2002–2013. Children under 12 months old were excluded to allow time for parents to have registered an objection to vaccination. We analysed the 2013 data further, mainly for children born 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2012.

The area of residence of children was defined as “major cities”, “inner regional”, “outer regional”, “remote” or “very remote” according to the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+).5 We combined the inner and outer regional categories into a single “regional” category, and the remote and very remote categories into a single “remote” category.

If a child was registered with Medicare later than 365 days after birth, we assumed that they had been born overseas.

We compared children living in postcodes in the bottom and top 10% of all postcodes with regard to economic resources, according to the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas: Index of Economic Resources.6 For small area analyses, we used Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Statistical Area 3 (SA3) areas.7 Maps were created using MapInfo version 12.0 (Pitney Bowes) and ABS census boundary information. The ABS Postal Area to SA3 Concordance 20118 was used to match ACIR postcodes to SA3.9 If a postcode was matched to more than one SA3, the SA3 with the greatest proportion of the population of that postcode was used.

Due to the extremely large number of children included in this study, statistical comparisons were unnecessary.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for this study, as de-identified population-based data were used only for routine public health surveillance.

Results

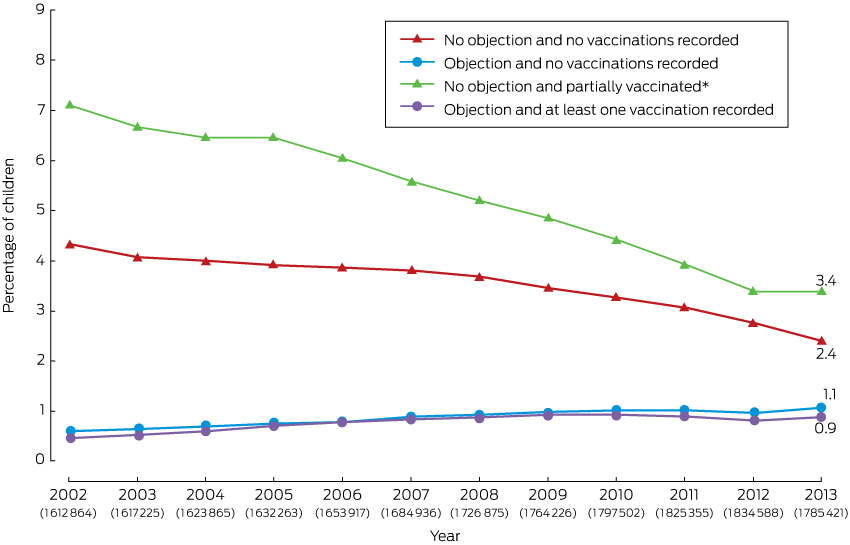

The percentage of children aged 1–6 years with a vaccination objection recorded on the ACIR increased from 1.1% (17 430 of 1 612 864 children) in 2002 to 2.0% in 2013 (1.1% [19 244/1 785 421] with no vaccinations recorded; 0.9% [15 917/1 785 421] with one or more vaccinations recorded; Box 1).

In contrast, the percentage of children for whom neither vaccinations nor an objection were recorded decreased from 4.3% (69 684/1 612 864) in 2002 to 2.4% (42 578/1 785 421) in 2013. The percentage of children who were partially vaccinated with respect to vaccines scheduled at 2, 4 and 6 months of age and for whom no objection was recorded also declined, from 7.1% (114 221/1 612 864) in 2002 to 3.4% (60 094/1 785 421) in 2013 (Box 1).

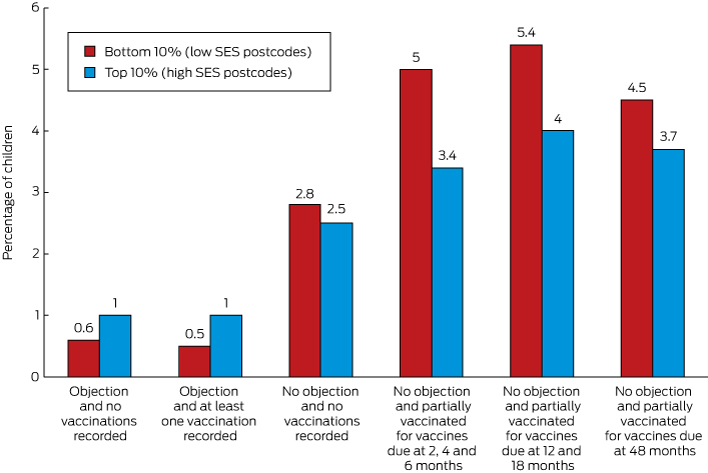

In 2013, the proportion of children with a recorded vaccination objection living in the lowest 10% of postcodes with regard to economic resources was about half that of those living in the highest 10% (1.1% [1664/152 279] v 1.9% [4598/236 649]; Box 2).

The proportion of children in the lowest socio-economic decile who were partially vaccinated and for whom there was no recorded objection was 50% higher than for those living in the most advantaged decile for vaccinations due at 2, 4 and 6 months of age (5.0% [7644/152 279] v 3.4% [8016/236 649]), 35% higher for vaccines due at 12 and 18 months of age (5.4% [6677/124 271] v 4.0% [7909/198 126]), and 20% higher for vaccines due at 48 months of age (4.5% [2023/44 897] v 3.7% [2807/75 890]).

The percentage of children with a vaccination objection recorded on the ACIR was 2.5% (11 342/462 237) in regional areas, 1.8% [22 973/1 268 599) in major cities, and 1.4% (536/39 062) in remote areas.

Children likely to have been born overseas (using the proxy measure of late Medicare registration) were less likely to have a recorded vaccination objection than other children (1.4% [1754/123 469] v 2.0% [33 407/1 661 952]), but much more likely to have neither an objection nor any vaccinations recorded (17.1% [21 134/123 469] v 1.2% [19 619/1 661 952]), or to have no recorded objection but to be partially vaccinated with respect to vaccines due at 2, 4 and 6 months of age (19.6% [24 241/123 469] v 2.1% [35 205/1 661 952]). Seventy-five per cent (145 091/194 757) of proxy overseas-born children lived in major cities, compared with 71% of other children (1 123 799/1 576 567); they comprised 52% of children with neither an objection nor any vaccinations recorded (21 134/40 753).

Some children with a vaccination objection documented on the ACIR were recorded as being fully vaccinated at the relevant age milestones. At 12 months of age, 23% of all children with a recorded objection (7946/35 161) were fully vaccinated; in 90% of these cases, the objection had been registered after receiving the third dose of the diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis vaccine. At 24 months of age, 15% of all children with a recorded objection (4606/30 910) were fully vaccinated; in 78% of these cases the objection had been registered after receiving the first dose of the measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine. At 60 months of age, 12% of all children with a recorded objection (3685/31 228) were fully vaccinated; in 25% of cases, the objection had been registered after receiving the second dose of the MMR vaccine (data not shown).

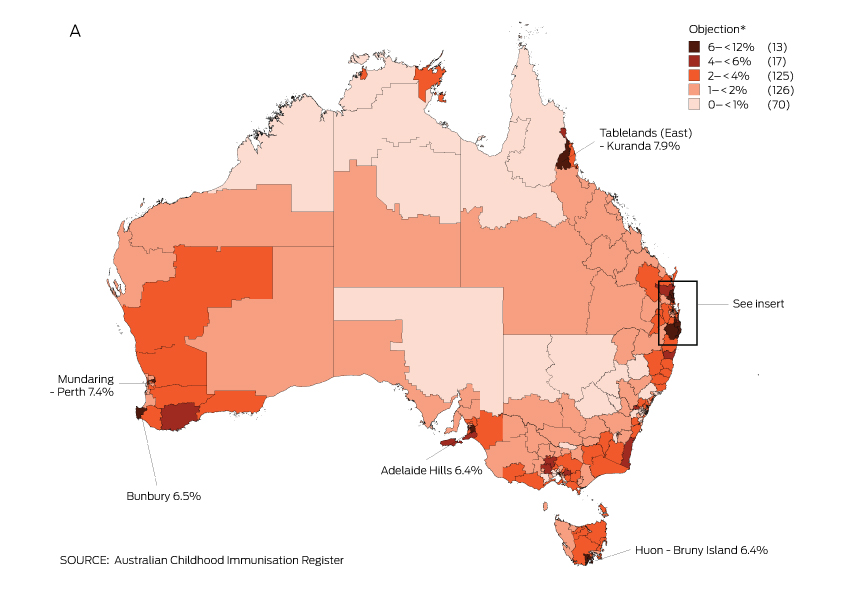

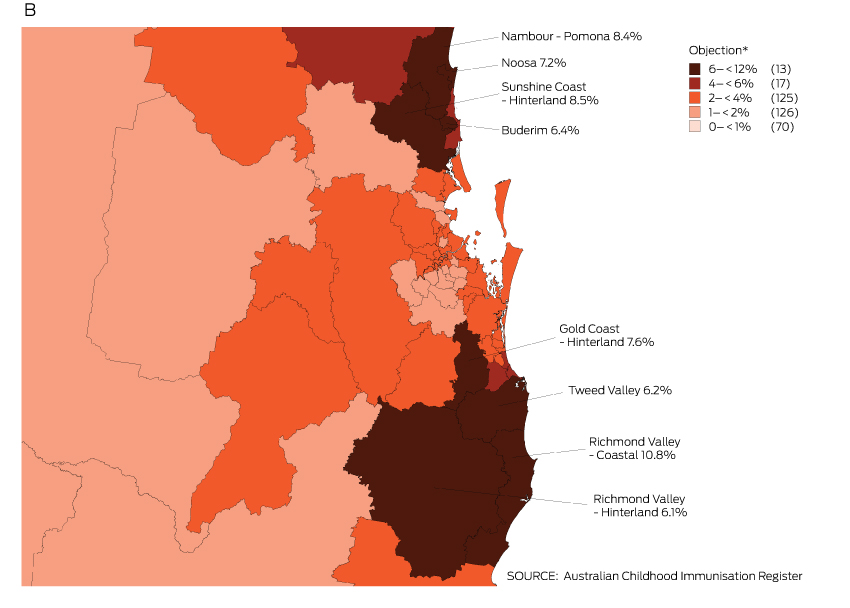

The proportion of children with an objection to vaccination recorded on the ACIR varied substantially at the small area level. Most areas with high levels of recorded objection were in regional zones, with marked clustering in northern New South Wales and south-east Queensland (Box 3).

Discussion

Registered objection to vaccination in Australia, as a percentage of the total population aged from 12 months to less than 7 years, increased by less than one percentage point between 2002 and 2013. During this period, the percentage of children with no recorded objection but incompletely vaccinated (either no vaccinations or only some scheduled vaccinations recorded) decreased, while vaccination coverage remained relatively high and stable.4,9 Contrary to frequent claims in the media, this suggests that overall levels of objection (registered and unregistered) have not changed, and increases in registered objection may have been driven by increased awareness that registration preserved eligibility for family assistance payments, which rose in value during this period.10

Among the 5.8% of children in 2013 who were incompletely vaccinated but with no recorded objection, potential explanatory factors include unregistered objection, reporting and recording errors, and problems of access, opportunity and logistics.

Our data show that for 2.4% of children there was no recorded objection but also no scheduled vaccinations recorded on the ACIR; of these children, 52% were likely to have been born overseas. This is consistent with findings from a recent study in Western Australia which found that 44% of children with no recorded objection or vaccinations had been born and vaccinated overseas; only 28% involved an unregistered objection.11,12 Extrapolating from these data, we estimate that the proportion of children in our study with no recorded vaccinations because of an unregistered objection was about 0.7% (ie, 28% × 2.4%; Box 4). Our finding that the percentage of children with no recorded objection and no recorded vaccinations is highest in major cities and lowest in regional areas is consistent with the greater proportion of overseas-born children in major cities.13 Estimation of true vaccination coverage needs to take overseas-born status into account, particularly at the small area level in major city locations, where recording and reporting errors may explain reports of apparently lower coverage.14,15

Another important subgroup of incompletely vaccinated children includes the 3.4% of children for whom there was no recorded objection, but who were only partially vaccinated with respect to vaccines due at 2, 4 and 6 months of age. This group included a substantially higher proportion of children living in the bottom 10% of socio-economic status postcodes, suggesting delayed vaccination caused by problems related to disadvantage, logistic difficulties, access to health services, and missed opportunities in primary, secondary and tertiary health care. Incomplete vaccination has previously been associated with socio-economic factors in Australian and overseas studies.16,17

In the absence of alternative data, we assumed that the ratio between the proportions of children affected by registered objection with some and no vaccinations (ie, 0.9:1.1) was similar to that for partially unvaccinated and completely unvaccinated children with unregistered objection. We consequently estimated that the proportion of children who were partially vaccinated as the result of an unregistered objection was about 0.6%. The estimated total proportion of children affected by a registered or unregistered objection to vaccination, ranging from those who have received no vaccinations to those who have received some or delayed vaccinations, was thus 3.3% (Box 4).

This figure includes fully vaccinated children with a registered objection. Our findings indicate that, at earlier vaccination milestones, the objection was typically registered after scheduled vaccinations were given. At the 60 months’ milestone, however, appropriate vaccinations had usually been given after the objection had been registered, which may reflect a change of mind by the parent(s) and subsequent (ie, delayed) vaccination.

The distribution of recorded vaccination objection shows marked geographical clustering, posing a risk of local disease outbreaks.18-21 Teasing out the various issues contributing to incomplete vaccination will be particularly important now that data on registered objection is no longer collected: from 1 January 2016, philosophical and religious beliefs are no longer legally valid reasons for exemption from vaccination requirements for receiving family assistance payments.22 Our findings provide a baseline against which to track trends in objection, although limitations include our use of ACIR data without directly interviewing parents, and the limited nature of recent information on the completeness and accuracy of ACIR data. The most recent national survey of parents of incompletely vaccinated children estimated in 2001 that 2.5–3.0% of the annual birth cohort were affected by parents who had registered an objection or had significant concerns about vaccination.2,23 Our estimate (3.3%) was only slightly higher, suggesting that there has been little change in the overall impact of vaccination objection since 2001. A national survey, focusing on incompletely vaccinated children, equipped to evaluate data quality, and using personal interviews to assess parental attitudes, would allow verification of our findings.

In light of our conclusions, primary care clinicians should pay close attention to ensuring that the vaccination history of overseas-born children is correctly recorded in the ACIR. Clinicians should also be on the alert for appropriate catch-up opportunities for partially vaccinated children, as in most cases they are probably not up to date for reasons other than parental objection.

Box 1 – Trends in recorded vaccination objection status and vaccination status of children aged from 12 months to less than 7 years, Australia, 2002–2013

* For vaccines due at 2, 4 and 6 months of age. The number of children in each annual cohort is given below the respective year number.

Box 2 – Recorded vaccination objection status by socio-economic status of area of residence and vaccination status, children aged 12 months to less than 7 years, Australia, 2013 (cohort born 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2012)*

* No objection and partially vaccinated with respect to vaccines due at 12 and 18 months: cohort born 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2011; no objection and partially vaccinated with respect to vaccines due at 48 months: cohort born 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2008. Addition of percentages may result in apparent discrepancies because of rounding.

Box 3 – Recorded vaccination objection by Statistical Area 3 (SA3), for children from 12 months to less than 7 years old, in (A) Australia and (B) south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales, 2013 (cohort born 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2012)

* Number of SA3s in each category in parentheses; SA3s in 6–< 12% category are named on the map.

Box 4 – Estimates of the proportions of children aged from 12 months to less than 7 years affected by registered and unregistered vaccination objection, Australia, 2013

Objection/immunisation status |

Proportion of child population |

Proportion of child population affected by objection |

|||||||||||||

A. Objection and no vaccinations recorded |

1.1% |

1.1% |

|||||||||||||

B. Objection and one or more vaccinations recorded |

0.9% |

0.9% |

|||||||||||||

C. No objection and no vaccinations recorded |

2.4% |

0.7%* |

|||||||||||||

D. No objection recorded and partially vaccinated |

3.4% |

0.6%† |

|||||||||||||

Total: 3.3% |

|||||||||||||||

* Assumption: 28% of total proportion (ie, 0.28 × 2.4%) are affected by unregistered objection (based on Western Australian study11,12). † Assumption: the ratio of children affected by unregistered objection who are partially vaccinated [D] and children affected by an unregistered objection for whom no vaccinations are recorded [C, adjusted] is similar to the ratio of children with a registered objection for whom some vaccinations are recorded [B] and those for whom no vaccinations are recorded [A]; ie, D = [B]/[A] × [C, adjusted] = 0.9/1.1 × 0.7%). | |||||||||||||||

Received 5 November 2015, accepted 29 February 2016

- Frank H Beard1,2

- Brynley P Hull1

- Julie Leask2

- Aditi Dey1,2

- Peter B McIntyre1

- 1 National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 2 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

The National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance is supported by the Australian Government Department of Health, the NSW Ministry of Health and the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of these agencies.

We are all employed full- or part-time by the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, which receives most of its funding from the Australian Government Department of Health.

- 1. Simmons A. More than 70,000 children not fully immunised. ABC News, 11 Apr 2013. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-04-11/children-across-australia-not-fully-imunised/4622666 (accessed Feb 2016).

- 2. Lawrence GL, Hull BP, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre PB. Reasons for incomplete immunisation among Australian children: a national survey of parents. Aust Fam Physician 2004; 33: 568-571.

- 3. Hull BP, McIntyre PB, Heath TC, Sayer GP. Measuring immunisation coverage in Australia: a review of the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register. Aust Fam Physician 1999; 28: 55-60.

- 4. Hull BP, Dey A, Menzies RI, et al. Annual report: immunisation coverage, 2012. Commun Dis Intell 2014; 38: E208-E231.

- 5. Australian Population and Migration Research Centre. ARIA and accessibility. Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia — ARIA+ (2011) [website]. Adelaide: APMRC, 2011. http://www.spatialonline.com.au/ARIA_2011/default.aspx (accessed Nov 2014).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa (accessed Nov 2014).

- 7. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS). Canberra: ABS, 2011. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/australian+statistical+geography+standard+%28asgs%29 (accessed Nov 2014).

- 8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Correspondences, July 2011. Canberra: ABS, 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&1270055006_cg_postcode_2011_sa3_2011.zip&1270.0.55.006&Data%20Cubes&07308A67BF786E9FCA257A4B0014E971&0&July%202011&31.07.2012&Latest (accessed Nov 2014).

- 9. Hull B, Dey A, Beard F, et al. Annual immunisation coverage report 2013. http://www.ncirs.edu.au/assets/surveillance/coverage/2013-coverage-report-final.pdf (accessed Feb 2016).

- 10. Ward K, Hull BP, Leask J. Financial incentives for childhood immunisation — a unique but changing Australian initiative. Med J Aust 2013; 198: 590-592. <MJA full text>

- 11. Gibbs RA, Hoskins C, Effler PV. Children with no vaccinations recorded on the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015; 39: 294-295.

- 12. Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Investigation of Western Australian children with no vaccinations recorded on the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register. Western Australia: Government of Western Australia, 2015. www.public.health.wa.gov.au/cproot/5941/3/Unvaccinated_children_on_ACIR.doc (accessed Nov 2015).

- 13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4102.0. Australian social trends, 2014. Where do migrants live? [website]. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0main+features102014 (accessed Oct 2015).

- 14. Ferson MJ, Orr K. Some truths about the “low” childhood vaccination coverage in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Med J Aust 2015; 203: 153. <MJA full text>

- 15. Hull BP, Lawrence GL, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre PB. Is low immunisation coverage in inner urban areas of Australia due to low uptake or poor notification? Aust Fam Physician 2003; 32: 1041-1043.

- 16. Bond L, Nolan T, Lester R. Immunisation uptake, services required and government incentives for users of formal day care. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999; 23: 368-376.

- 17. Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia E. Factors associated with suboptimal compliance to vaccinations in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 1719-1741.

- 18. Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, et al. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics 2013; 132: 624-630.

- 19. Omer SB, Enger KS, Moulton LH, et al. Geographic clustering of nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements and associations with geographic clustering of pertussis. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 1389-1396.

- 20. Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Gallagher K, et al. Measles in the United States during the postelimination era. J Infect Dis 2010; 202: 1520-1528.

- 21. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Measles — United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61: 253-257.

- 22. Australian Government Department of Health. No jab, no pay — new immunisation requirements for family assistance payments. 2015. www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/67D8681A67167949CA257E2E000EE07D/$File/No-Jab-No-Pay.pdf (accessed Jan 2016).

- 23. Hull B, Lawrence G, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre P. Immunisation coverage: Australia 2001. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 2002.

Abstract

Objectives: To examine geographic and demographic trends in objection to vaccination in Australia.

Design: Cross-sectional analysis of Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) data (2002–2013) for children aged 1–6 years.

Main outcome measures: Immunisation status according to whether an objection had been registered, and remoteness and socio-economic status of area of residence. Registration of children with Medicare after 12 months of age was used as a proxy indicator of being overseas-born.

Results: The proportion of children affected by a registered vaccination objection increased from 1.1% in 2002 to 2.0% in 2013. Children with a registered objection were clustered in regional areas. The proportion was lower among children living in areas in the lowest decile of socio-economic status (1.1%) than in areas in the highest socio-economic decile (1.9%). The proportion not affected by a recorded objection but who were only partly vaccinated for vaccines due at 2, 4 and 6 months of age was higher among those in the lowest decile (5.0% v 3.4%), suggesting problems of access to health services, missed opportunities, and logistic difficulties. The proportion of proxy overseas-born for whom neither vaccinations nor an objection were recorded was 14 times higher than for other children (17.1% v 1.2%). These children, who are likely to be vaccinated although this is not recorded on the ACIR, resided predominantly in major cities.

Conclusions: There was a small increase in registered objection rates since 2002. We estimate that 3.3% of children are affected by registered or presumptive (unregistered) vaccination objection, which suggests that the overall impact of vaccination objection on vaccination rates has remained largely unchanged since 2001. Incomplete records, barriers to access, and missed opportunities are likely to be responsible for most other deficiencies in vaccination coverage.