Clinical record

16-year-old male presented to the emergency department after ingesting what he believed to be LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) on red blotting paper while camping with friends in rural New South Wales in late 2014. He had no past medical or mental health history, and was taking no regular medications. He had three seizures before arriving in the ED, where his Glasgow coma scale score was 9. He had a fourth seizure about 1 hour after presenting, and was given 5 mg midazolam intravenously. His initial venous blood gas parameters were: pH 6.93 (reference range [RR], 7.35–7.45); PCO2, 120 mmHg (RR, 35–48 mmHg); and base excess, −7 (RR, 0.5–1.6). He was then intubated, ventilated, paralysed with rocuronium, and sedated with morphine/midazolam for transfer to a tertiary intensive care unit. His heart rate was 70 bpm, his blood pressure 130/60 mmHg, and he was afebrile after intubation. Over the next 3 hours and before medical retrieval, his blood gases normalised with improved ventilation (pH 7.4; PCO2, 29.6 mmHg).

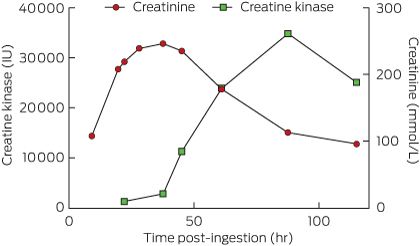

He had no further seizures after his transfer to the tertiary intensive care unit. His overnight urine output was initially reduced; this improved with increased fluid replacement. On arrival at the intensive care unit, his blood parameters were: white cell count, 16.3 × 109/L (RR, 4–11 × 109/L); neutrophils 12.1 × 109/L (RR, 1.7–8.8 × 109/L); haemoglobin, 136 g/L (RR, 130–180 g/L); platelets, 198 × 109/L (RR, 150–400 × 109/L); sodium, 142 mM (RR, 134–145 mM); potassium, 3.9 mM (RR, 3.5–5.0 mM); and creatinine, 108 mM (64–104 mM). He remained haemodynamically stable and was extubated the following day. He was transferred to the paediatric ward, and on Day 2 his creatinine and creatine kinase levels were rising, with normal urine output (Figure). Except for some initial nausea that lasted for 24 hours after extubation, he had no other symptoms over the next 3 days, and experienced no hallucinations or agitation. His creatinine levels peaked at 246 mM [RR, 64–104 mM] 37.5 hours after ingestion, and his creatine kinase levels peaked at 34 778 U/L (RR, 1–370 U/L) 90 hours after ingestion. He was discharged well on Day 5 without complications.

NBOMe assays are not currently part of routine emergency toxicology testing; worldwide, only a few forensic and commercial laboratories offer qualitative NBOMe testing in blood or urine. Blood specimens from the patient were sent to the Department of Pathology at Virginia Commonwealth University (USA) for NBOMe detection and quantification. The specimens were tested by previously validated high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry assays.1,2 25B-NBOMe was detected in the blood specimen at a concentration of 0.089 μg/L, 22 hours after ingestion.

Dimethoxyphenyl-N-[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine derivatives (NBOMes) are a novel class of potent synthetic hallucinogens originally developed as 5-HT2 receptor agonists for research purposes, but which have become available as recreational drugs in the past few years.3 They are available under a number of street names, including “N-bombs”, and are often sold as “acid” or “LSD” on blotting paper, as a powder, or as blue tablets (“blue batman”). They have been increasingly associated over the past 2 years with deaths and severe toxicity in North America and Europe.3–5 Most reports have concerned 25I-NBOMe intoxication, and there is much less information on the 25B- and 25C-NBOMe derivatives.2,6,7 While difficult to assess because of the sparse number of reports, 25B-NBOMe may be more toxic than the more commonly reported 25I-NBOMe.3,4 Our case is consistent with previous reports of severe NBOMe toxicity, with agitation, tachycardia and mild hypertension, seizures, rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury.3

There have been few reports of NBOMe poisoning in Australia, and only one report of a fatality.8 Most reports in Australia have been in the popular media, describing the presence of NBOMes in this country. There is limited information available to health care professionals about their potential toxicity. An international online survey in 2012 found that NBOMes were being used in Australia, although not as commonly as in the United States.5 NBOMes are reported to be relatively inexpensive, and are usually purchased over the internet. For this reason, as in our case, intoxicated NBOMe users may present to rural and smaller regional hospitals. As in other reports, our patient believed he had taken “acid” or LSD. The one reported death in Western Australia involved a woman who had inhaled a white powder she thought to be “synthetic LSD”; she began behaving oddly, before collapsing and dying.8 In comparison with the dramatic systemic effects seen in our case and those described in the literature, LSD is not associated with such severe medical complications.9

NBOMe toxicity is characterised by hallucinations and acute behavioural disturbance, with seizures, rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in more severe cases.3,4,6,9,10 Our patient was postictal when he presented, and required immediate sedation and intubation, after which he was reported to have a normal heart rate and blood pressure. Rising creatinine and creatine kinase levels were recognised on the medical ward after the patient had been extubated.

Previous reviews3,4 suggested that there are two different presentation types of NBOMe toxicity: one form dominated by hallucinations and agitation, and another involving more severe medical complications. Patients presenting with the first type should be managed in a similar manner to other patients with acute behavioural disturbance, including verbal de-escalation and oral or parenteral sedation as required.11 In many cases, these patients will present with undifferentiated behavioural disturbance, and only the persistence of hallucinations or agitation and the history given by the patient will suggest the diagnosis. In patients with more severe medical complications, directed supportive care is appropriate, including intubation and ventilation for coma, and fluid replacement for rhabdomyolysis and acute renal impairment. Serial electrolyte, creatinine and creatine kinase measurements should be made in all cases to identify these complications and to monitor the progress of the patient. Further, such investigations may potentially play a role in identifying NBOMe as a cause in patients who present with undifferentiated agitation and hallucinations lasting 24 hours or more.Lessons from practice

Dimethoxyphenyl-N-[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine derivatives (NBOMes) are hallucinogenic substances that have become available as drugs of misuse in the past few years.

NBOMe toxicity can cause acute behavioural disturbance, and in severe cases can cause seizures, rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury.

NBOMes may be distributed as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or “acid” on blotting paper.

Treatment is supportive, including sedation for agitation and intravenous fluid therapy for rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.

Clinicians need to be aware that newer synthetic hallucinogens, such as NBOMes, are available in Australia, and that patients may believe them to be “acid” or LSD. NBOMes cause prolonged agitation and hallucinations and, in more severe cases, seizures, rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury.

- Geoffrey K Isbister1

- Alphonse Poklis3

- Justin L Poklis3

- Jeffrey Grice4

- 1 University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 2 Calvary Mater Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 3 Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va

- 4 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

Geoffrey Isbister is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1061041). The ability to collect and transport samples for drug analysis is supported by an NHMRC Program Grant (1055176).

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Poklis JL, Charles J, Wolf CE, Poklis A. High-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of 2CC-NBOMe and 25I-NBOMe in human serum. Biomed Chromatogr 2013; 27: 1794-1800.

- 2. Poklis JL, Nanco CR, Troendle MM, et al. Determination of 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxy-N-[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-benzeneethanamine (25B-NBOMe) in serum and urine by high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry in a case of severe intoxication. Drug Test Anal 2014; 6: 764-769.

- 3. Suzuki J, Dekker MA, Valenti ES, et al. Toxicities associated with NBOMe ingestion — a novel class of potent hallucinogens: a review of the literature. Psychosomatics 2015; 56: 129-39.

- 4. Wood DM, Sedefov R, Cunningham A, Dargan PI. Prevalence of use and acute toxicity associated with the use of NBOMe drugs. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015; 53: 85-92.

- 5. Lawn W, Barratt M, Williams M, et al. The NBOMe hallucinogenic drug series: patterns of use, characteristics of users and self-reported effects in a large international sample. J Psychopharmacol 2014; 28: 780-788.

- 6. Tang MH, Ching CK, Tsui MS, et al. Two cases of severe intoxication associated with analytically confirmed use of the novel psychoactive substances 25B-NBOMe and 25C-NBOMe. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014; 52: 561-565.

- 7. Armenian P, Gerona RR. The electric Kool-Aid NBOMe test: LC-TOF/MS confirmed 2C-C-NBOMe (25C) intoxication at Burning Man. Am J Emerg Med 2014; 32: 1444.e3-e5.

- 8. Kueppers VB, Cooke CT. 25I-NBOMe related death in Australia: a case report. Forensic Sci Int 2015; 249: e15-e18.

- 9. Walterscheid JP, Phillips GT, Lopez AE, et al. Pathological findings in 2 cases of fatal 25I-NBOMe toxicity. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2014; 35: 20-25.

- 10. Rose SR, Poklis JL, Poklis A. A case of 25I-NBOMe (25-I) intoxication: a new potent 5-HT2A agonist designer drug. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013; 51: 174-177.

- 11. Calver L, Page CB, Downes MA, et al. The safety and effectiveness of droperidol for sedation of acute behavioral disturbance in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 66: 230-238.e1.

David Caldicott

We would advise treating physicians not to assume that NBOME-like products are exclusively available and consumed in ‘blotter’ form. The ACT Investigation of Novel Substances group (ACTINOS) has previously alerted the public and consumers to a pill, purchased as ‘ecstasy’, which was analysed by the ACTINOS Group as containing both 25C-NBOME & 25I-NBOME3,4. We would emphasize the importance of treating patients on the basis of the constellation of clinical findings, and not merely assumptions based on the mode or vehicle of ingestion.

We also applaud the lengths to which the group has gone to positively identify the agent involved in their case. Too frequently, conclusions are made regarding the nature of novel ingestions, based almost exclusively on hearsay and supposition5. We also note that the analysis described in the case report was conducted in the USA. The expertise to conduct these analyses exists in Australia, but frequently, either as consequence of cost to researchers, or inaccessibility to forensic / law enforcement laboratories, the pursuit of analysis to definitive identification and characterization is frequently abandoned. Given the evident acceleration of the rate of emergence of these new and dangerous products, we reiterate our calls for greater collaboration between clinical and forensic toxicologists, and further support for health care providers to identify both the ‘known-‘ and ‘unknown-unknowns’, as they are released on the market.

1) Isbister GK, Poklis A, Poklis JL, Grice J. Beware of blotting paper hallucinogens: severe toxicity with NBOMes. Med J Aust. 2015 Sep 21;203(6):266-7.

2) Caldicott DG, Bright SJ, Barratt MJ NBOMe - a very different kettle of fish . . . Med J Aust. 2013 Sep 2;199(5):322-3.

3) http://actinos.org/?q=novelproducts/14/view

4) Colley, C. ED doctor warns dangerous new party drug set to blow out Canberra summer scene, Canberra Times, November 13, 2014, Available at

http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/ed-doctor-warns-dangerous-new-party-drug-set-to-blow-out-canberra-summer-scene-20141113-11m4s3.html#ixzz3mdf1yT2W , Accessed 24th September 2015

5) McCutcheon DS, Oosthuizen FJ, Hoggett KA, Fatovich DM. A bolt out of the blue: the night of the blue pills. Med J Aust. 2015 Jun 1;202(10):543.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Assoc Prof David Caldicott

University of Canberra / Australian National University