The OECD warns about Australia’s low psychiatric bed numbers

In April 2015, the federal government released the National Mental Health Commission (NMHC) report on the Australian mental health sector.1 Although the report contained many consensus-driven, consumer-oriented proposals, the media focused on the recommended shift of $1 billion from public acute-care hospitals over 5 years to expand community mental health programs including subacute beds.2

The NMHC schedule reduces mental health funding for acute hospitals progressively from the 2017–18 financial year (Box 1).1 Given that total funding was $1.4 billion in the 2012–13 financial year, the reallocation of at least $300 million in the final year of the schedule (2021–22) could reduce the number of acute-care hospital beds by 15%.

As an independent commission, the NMHC has encouraged debate about their report. In a recent article in the Journal, Professor Ian Hickie, an NMHC Commissioner, supported “shifting the emphasis” from acute hospitals to community-based services, and he urged the federal government to act.2 The NMHC chair, Professor Allan Fels, echoed these views in his National Press Club Address in August 2015.3 He criticised federal government expenditure on acute-care hospitals as “payment for failure” and argued that mental health problems should be treated earlier to “catch people before they fall”.

The NMHC report is not without its critics. Australian peak medical bodies suggested that the cuts to acute bed numbers could cost lives. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) argued that the NMHC report ignored the already excessive demand on Australia’s psychiatric wards and emergency departments (EDs).4 The Australian Medical Association (AMA) has also lobbied against acute bed closures, which can block admissions when the risks of suicide and aggression are higher.

These medical experts suggested that Australia’s mental health sector has reached the tipping point of high bed occupancy and extended ED waiting times. If this is correct, Australia needs to commission more acute psychiatric beds and maintain bed occupancy rates below 85%, in order to guarantee the safe functioning of acute hospitals.5

The debate around the public positions of the NMHC and peak medical bodies raises a series of important questions. Does Australia have too many acute psychiatric beds, and can the nation safely make savings by reducing future funding for acute hospitals? How would acute bed closures affect patient care?

The OECD warning

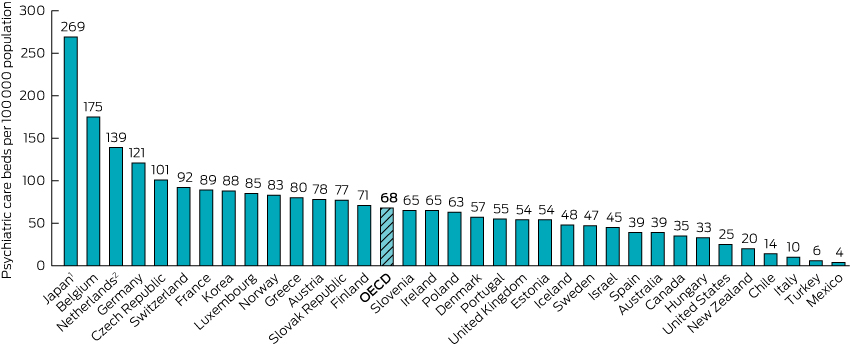

The NMHC report’s recommended acute bed closures would begin from a low base by international standards. Australia is ranked 26th of the 34 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for hospital psychiatric beds per 100 000 population (Box 2).6 In 2013, Australia had 29 fewer beds per 100 000 than the OECD average. Anglosphere countries such as Australia, Canada, the United States and New Zealand tended to have lower bed numbers than the wealthy European nations, with the United Kingdom showing a European influence by having 15 more beds per 100 000 than Australia.

The OECD warned that Australia’s low psychiatric bed numbers increased the risks of worsening symptoms before acute admission.6 These patient risks depended on the “tricky balance” between inpatient care, community services, primary mental health care, and social capital including cooperative networks of carers, extended families and neighbourhoods.

In Australia, the nation seeks to compensate for low acute bed numbers by funding numerous community mental health services.6 In these circumstances, community services must be able to assist patients during the acute phase of their illness either to avert admission or to help patients immediately after discharge.

As Australia’s acute bed occupancy rates are high and patients have a short average length of stay (LOS), patients are often discharged before pharmacotherapy is optimally effective (Australia’s average LOS is 17 days). The 30-day hospital unplanned readmission rate provides a measure of how well community services offset short LOS. In 2011, Australia had the third highest readmission rate among the OECD countries for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia with over 15% being readmitted to hospital within 30 days, and the fourth highest unplanned readmission rate of 15% for patients with bipolar disorder.7 Australia’s readmission rate was higher than that of the UK, where more acute beds allowed longer admissions (the UK average LOS was 30 days versus the Australian average of 17 days); this ensured adequate acute treatment in the UK, which was accompanied by lower readmission rates (5%–10%).7

There was a significant increase in UK readmission rates from 2006 to 2011, which corresponded with a period of acute bed closures.7 As Fels3 noted, the UK government was “trying to manage cutting back hospital spending” in mental health. While hospital psychiatric bed numbers remained considerably higher in the UK than in Australia, these spending cuts created debate. In 2011, distinguished community psychiatrist Professor Peter Tyrer contended that the closure of psychiatric beds had gone too far in the UK, and the risk of preventing admissions was becoming too great.8 He concluded that inpatient care had been “demonised” by community psychiatry advocates who had captured national policy, and he suggested that the UK needed new policies that recognised the unique value of inpatient care. His argument could equally well be applied to Australia.

Emergency demand

South Australian data provide evidence of the excessive mental health demand on acute hospitals. From July 2011, SA anticipated the NMHC report recommendations by transferring funding from acute hospitals to fund community subacute beds.9 Over this period, SA was the only state decommissioning recently mainstreamed acute beds; other states were increasing acute bed numbers consistent with population growth. By 2014, SA was 20% below the Australian average for non-veteran general adult acute hospital beds (for 18–65-year-olds), with double the average number of community beds.

It soon became apparent, however, that these subacute beds were not substituting for the decommissioned acute beds as intended.9 The central problem was risk management. The subacute units were built and staffed for patients at minimal risk of suicide and aggression. This meant that only patients with low-risk presentations could be referred from the community or acute hospitals to the subacute units. Before the subacute units, most of these patients would have been treated at home.

Hence, the SA psychiatric bed mix left a gap in acute care, which resulted in increasing average ED total visit times for mental health patients in metropolitan hospitals over 2011–2014 (Box 3). Average ED visit times peaked at 15.7 hours in October 2014. These average ED visit times reflected the extended periods that mental health patients waited for admission (33.5 hours for mental health patients on average versus 9.3 hours for non-mental health patients in 2014). Of particular concern, 2450 mental health patients waited more than 24 hours in busy and overstimulating ED environments during 2014 (representing 17.5% of the mental health presentations to SA hospital EDs).10

Responding to patient need and community concern, in December 2014, the SA government commissioned 20 beds in metropolitan hospitals to return the state to the national average. The government’s revised strategy targeted investment towards psychiatric short-stay units in acute hospitals (14 beds) allowing up to 48-hour admissions. Early signs were positive, especially in those hospitals with the short-stay beds. For instance, average ED visit times reduced from 12.3 hours in 2014 to 6.7 hours during 2015 following the opening of 8 short-stay psychiatry beds at Flinders Medical Centre in December 2014. The short-stay units provided a dedicated environment for acute presentations enabling improved ED flow, which regional subacute beds had been unable to achieve.

Conclusion

Australia’s low acute bed numbers can block access for mental health patients when the risks of suicide and aggression are higher. The OECD 30-day readmission rates and the SA experience suggest that these problems are not being offset by Australia’s numerous community mental health services, including the expansion of subacute beds in SA. Overall, the data support RANZCP and AMA concerns that Australian acute hospitals are facing excessive mental health demand.

When ED waiting times and 30-day readmission rates are excessive, it is not possible to safely reduce acute hospital funding and close beds. Quite the opposite policy is required; more acute beds should be commissioned when mental health patients are waiting far longer for admission than medical or surgical patients, as occurred recently in SA. Clinical opinion suggests that these issues are not isolated to SA but are occurring in acute hospitals around the country. It is time for policy planners to reflect on the OECD warning, and urgently tackle this huge national problem.

The federal government convened an Expert Reference Group to provide a fresh perspective on the NMHC report. This presents Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and the government with an ideal opportunity to carefully evaluate mental health demand on acute hospitals, and to ensure adequate activity-based funding for acute psychiatric beds. This expenditure should not be regarded as “payment for failure”; it is a minimal investment in the compassionate care of mental health patients when they are most unwell, which is the standard required in every area of medicine in Australia.

Box 1 – The National Mental Health Commission schedule for reducing acute hospital funding1

Financial year |

Minimum reallocation ($ million) |

||||||||||||||

2017–18 |

$100 |

||||||||||||||

2018–19 |

$150 |

||||||||||||||

2019–20 |

$200 |

||||||||||||||

2020–21 |

$250 |

||||||||||||||

2021–22 |

$300 |

||||||||||||||

Total |

$1000 |

||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Comparison of psychiatric bed numbers in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, 20116

1. In Japan, a high number of psychiatric care beds are used by long-stay patients. 2. In the Netherlands, psychiatric bed numbers include social care sector beds that may not be included as psychiatric beds in other countries. Source: OECD Health Statistics 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en. Reproduced with permission from the OECD.

Box 3 – Mean total visit times for mental health patients in the emergency departments (EDs) of South Australian metropolitan hospitals (2011–2015)10

Time period |

Mean total ED visit time (hours) |

||||||||||||||

July – December 2011 |

8.9 |

||||||||||||||

January – June 2012 |

8.4 |

||||||||||||||

July – December 2012 |

10.2 |

||||||||||||||

January – June 2013 |

10.2 |

||||||||||||||

July – December 2013 |

11.4 |

||||||||||||||

January – June 2014 |

12.3 |

||||||||||||||

July – December 2014 |

14.5 |

||||||||||||||

January – August 2015 |

11.5 |

||||||||||||||

Provenance: <p>Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.</p>

- Stephen Allison1

- Tarun Bastiampillai1,2

- 1 Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

- 2 South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. National Mental Health Commission. Contributing lives, thriving communities. Report of the National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Sydney: NMHC, 2014. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/our-reports/contributing-lives,-thriving-communities-review-of-mental-health-programmes-and-services.aspx (accessed Sep 2015).

- 2. Hickie I. Time to implement national mental health reform. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 515-517. <MJA full text>

- 3. Fels A. Time to aim higher. Why mental health must be part of Australia's economic and social reform agenda. National Press Club Address. 5 Aug 2015. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media-centre/news/national-press-club-address.aspx (accessed Sep 2015).

- 4. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Cuts to mental health acute care ill-advised say psychiatrists. Melbourne: RANZCP, 2015. http://www.ranzcp.org/News-policy/Media-Centre/Media/Cuts-to-mental-health-acute-care-ill-advised-say-p.aspx (accessed Jun 2015).

- 5. Bagust A, Place M, Posnett JW. Dynamics of bed use in accommodating emergency admissions: stochastic simulation model. BMJ 1999; 319: 155-158.

- 6. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Australia at the forefront of mental health care innovation but should remain attentive to population needs, says OECD. Paris: OECD, 2014. http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/MMHC-Country-Press-Note-Australia.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2013-en (accessed Sep 2015).

- 8. Tyrer P. Has the closure of psychiatric beds gone too far? Yes. BMJ 2011; 343: d7457.

- 9. Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Goldney R. Acute versus subacute beds: should Australia invest in community beds at the expense of hospital beds? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48: 952-954.

- 10. KPMG. South Australia Health. Review of consumer flow across the mental health stepped system of care. Final report March 2015. https://www.anmfsa.org.au/news-archive/mental-health-clinical-redesignkpmg-review (accessed Jun 2015).

Gunvant Patel

To compound the plight, the very same lack of beds means they remain unable to be treated for lengthier periods whilst in custody. An appealing pragmatic solution to enforce treatment in custody is advocated by some as the understandable desperation has built.

However this flies in the face of ethical, legal, clinical and societal arguments centred on achieving parity of care for the mentally ill; particularly so when they are also held in the restrictive control-oriented confines of a prison.

To support such a move is to let off the hook successive governments who have failed to provide the much needed acute beds (and would no doubt reduce any pressure on them to do so). The medical profession should not collude in this regressive intervention and must continue to advocate for acute mental health beds.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Gunvant Patel

Forensicare