Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the frequency and age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children aged under 7 years living in Australia.

Design and participants: Analysis of de-identified data on 15 074 children aged under 7 years registered with the Helping Children with Autism Package (HCWAP; a program that provides funding for access to early intervention and support services throughout Australia) between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2012.

Main outcome measures: Age at diagnosis of ASD as confirmed by a paediatrician, psychiatrist and/or multidisciplinary team assessment.

Results: The average age at diagnosis of ASD in children registered with the HCWAP is currently 49 months, with the most frequently reported age being 71 months. Differences were evident in age at diagnosis across states, with children in Western Australia and New South Wales being diagnosed at a younger age. Across Australia, 0.74% of the population of children aged under 7 years are currently diagnosed with ASD and registered with the HCWAP. A higher proportion of children were registered with the HCWAP in Victoria compared with other states. There was no difference in age at diagnosis between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, but children from a culturally and linguistically diverse background were diagnosed 5 months earlier than other children.

Conclusions: There may be a substantial gap between the age at which a reliable and accurate diagnosis of ASD is possible and the average age that children are currently diagnosed. The frequency of ASD diagnoses in Australia has increased substantially from previously published estimates.

The early diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a critical step in gaining access to early intervention, providing optimal opportunity for developmental benefits by taking advantage of early brain plasticity.1 The age at which intervention begins has been associated with improved outcomes, with younger children showing greater gains from intensive early intervention.2,3 Although research suggests ASD can be reliably diagnosed by the age of 24 months,4,5 a recent review found that, on average, diagnosis is delayed until 3 years, with the average age at diagnosis ranging from 38 to 120 months across 42 studies conducted across the United States, United Kingdom, Europe, Canada, India, Taiwan and Australia.6

Many factors have been found to influence the age at which ASD is diagnosed, including the characteristics of the child, the clinical presentation, sociodemographic characteristics, and parental concerns and behaviour.6 These factors may interact with characteristics of the local community, the health professional and health service to differentially influence the age at which children are identified and diagnosed with ASD in any local area.6

There are limited data on the age and frequency of ASD diagnoses across all states and territories in Australia which, given the ethnically diverse and geographically dispersed population, would provide an important national and international comparison.

In this study, we sought to establish the age at which children registered with the Helping Children with Autism Package (HCWAP) in Australia currently receive a diagnosis. We also investigated trends in diagnosis across states, regional and rural areas, and child characteristics. Diagnostic groups within the autism spectrum, as specified in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV),7 as well as the combined ASD group (consistent with fifth edition of the DSM8) were examined, to facilitate comparisons over time.

Methods

Study population and measures

We used de-identified data on 15 074 children (12 183 boys [81%] and 2891 girls [19%]) who received support through the HCWAP between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2012. Data were collected and managed by the former Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA; now the Department of Social Services). To be eligible for the HCWAP, children must be Australian residents, aged under 7 years and have a documented diagnosis of ASD consistent with DSM-IV criteria from a paediatrician or psychiatrist, or after a multidisciplinary team assessment (involving a psychologist and speech pathologist).

The database contained the following information: age at diagnosis (months), state and postcode of residence, diagnosis, sex, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status. The postcode was used to match age at diagnosis to geographical and population data.

Ethics approval was received from the La Trobe University Faculty of Science, Technology and Engineering Human Ethics Committee.

Age at diagnosis

Children's age at diagnosis was calculated by subtracting their date of birth from the month and year that their diagnosis was confirmed, and rounded to the closest month.

Accessibility/remoteness index of Australia

The Accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA), developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, is a measure of remoteness, aggregated into the following categories: major cities; inner regional; outer regional; remote; very remote and migratory.

Estimates

The numbers of children at each year of age under 7 years (obtained from Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates) were summed and averaged over the period of 30 June 2010 to 30 June 2012 to create population estimates aligned to the study period and age group.

The estimated incidence of ASD was conservatively calculated as 1% of the population of children aged 0–7 years, based on estimates presented in the research literature from Australia (1/119 or 0.84%,9 1/106 or 0.94%10) the UK (98/10 000 or 0.98%)11 and US (1/68 or 1.47%).12

Statistical analysis

We conducted non-parametric comparisons (Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U-Tests) because age at diagnosis for the study population was not normally distributed, and sample size varied across groups. Bonferroni adjustments controlled for multiple comparisons, and a conservative α (P < 0.01) was adopted.

Results

Age at diagnosis

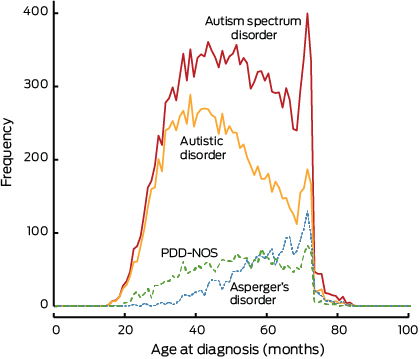

The average age at diagnosis of ASD between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2012 in children aged under 7 years and registered with the HCWAP was 49 months. As shown in Box 1, children with autistic disorder were diagnosed 7 months earlier than children with pervasive developmental disorder — not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and 16 months earlier than children with Asperger's disorder (AspD) (χ2 = 1614.67; df = 2; P < 0.001; ɳ² = 0.11). Less than 3% of children with ASD were diagnosed by 24 months (Box 2). A clear spike in the frequency distribution of age at diagnosis was evident at 71 months (Box 3), indicating the most frequently reported age at diagnosis of ASD (under 7 years) nationwide in the HCWAP database.

Mapping the average age at diagnosis of ASD in children registered with the HCWAP across Australia showed small but significant differences between states (χ2 = 146.69; df = 7; P < 0.001; ɳ² = 0.01). To reduce the number of post-hoc comparisons, states were grouped into logical clusters by ascending age at diagnosis. There were significant differences in age at diagnosis between these clusters of states, with children registered with the HCWAP in Western Australia and New South Wales diagnosed earlier than in other states (Box 4).

Frequency of autism spectrum disorder diagnoses

On the basis of HCWAP data, 0.74% of children aged under 7 years in Australia (72/10 000) were diagnosed with ASD between 2010 and 2012. Case ascertainment rates were calculated to determine if differences could be attributed to the number of children at an eligible age. Using 95% CIs, state-level differences were evident, with the highest ascertainment rate in Victoria and lowest in the Northern Territory (Box 4). Differences were also evident between states across diagnostic subgroups; using 95% CIs, a smaller proportion of children than expected with AspD were diagnosed in WA, Tasmania and the NT compared with other states (Appendix 1).

Age at diagnosis by remoteness

Significant differences in age at diagnosis were evident between major cities and regional areas (χ2 = 61.64; df = 4; P < 0.001; ɳ² = 0.004; Appendix 2). There was no statistically significant difference in age at diagnosis across major cities, remote and very remote areas, probably because of differences in sample size between these groups. However, ASD was diagnosed, on average, slightly earlier in remote areas, and 5 months later in very remote areas, compared with in major cities, although these differences were not significant.

Age at and frequency of diagnosis by child characteristics

Although girls registered with HCWAP were diagnosed, on average, 1 month earlier (48 months) than boys (49 months), this difference was not significant considering the conservative α adopted (U = 17 177 845; z = − 2.06; P = 0.04; r = 0.02). No difference was evident in the age at diagnosis of children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin registered with HCWAP (U = 3 455 468.5; z = − 1.77; P = 0.08; r = 0.02), but children from a CALD background were diagnosed, on average, 5 months earlier (U = 9 444 467.5; z = − 10.36; P < 0.001; r = 0.08). On the basis of 95% CIs, a smaller than expected proportion of children of CALD and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds with AspD were identified (Appendix 3).

Discussion

The average age at diagnosis of ASD in children aged under 7 years registered with HCWAP is 49 months, with the most frequently reported age being 71 months. Given that research suggests a reliable and accurate diagnosis is possible for many children with ASD at 24 months,4,5 this finding represents a possible average delay of 2 years (and common delays of up to 4 years).

The increase in frequency of ASD diagnoses at 6 years of age may be attributable to children's ASD being identified when they enter school, aged about 5 years, and the associated delay for diagnostic assessments. The end of the eligibility period for funding through the HCWAP (at age 7) may also contribute to the increase in diagnoses at 6 years of age. Further, there may be a subgroup of children who are diagnosed later because of factors in their clinical presentation, such as comorbid conditions or the presentation being less severe.

Previous research reported an average age at diagnosis of 4 years in WA and 3 years in NSW in 1999 to 2000,13 with a decrease in age at diagnosis from 4 to 3 years in WA between 1983 and 2004.14 In comparison, we found an average age at diagnosis of 3 years and 10 months in WA and 3 years and 11 months in NSW. These differences may reflect differences in study methods; for example, Nassar et al used the year of entering the data registry as a proxy variable for age at diagnosis in 77% of cases, and the difference between studies may therefore be explained by the limited accuracy of this variable.14

The number of children currently diagnosed with ASD and registered with the HCWAP suggests that the incidence of ASD in Australia has increased substantially from previous estimates. In 1999–2000, the incidence of ASD in 0–4-year-olds was reported to be 5.1 per 10 000 in NSW and 8.0 per 10 000 in WA.14 The national prevalence of ASD in 0–5-year-olds was estimated to increase from 16.1 to 22.0 per 10 000 from 2003 to 2005.15 Our study indicates that more than three times this many children are currently diagnosed with ASD and registered with the HCWAP. While reasons for the observed increase in ASD diagnoses remain largely unknown, many possible contributing factors have been suggested, including changes to the diagnostic criteria, improved awareness and diagnostic sensitivity.16

Delays of 3 to 6 months in age at diagnosis were evident between states, which may be clinically meaningful if they translate into equivalent delays in access to early intervention and family support services. Local differences in age at diagnosis have also been reported in the UK,17 US18 and Canada;19 suggesting that characteristics of local health care systems play a role in determining diagnostic timing.

Case ascertainment rates indicate that a larger proportion of children with ASD were identified in Vic and less than half of the expected children with ASD were identified in WA, the ACT and NT. There are many possible reasons for these differences, including the uptake of HCWAP across states, diagnostic substitution, and/or a greater tendency to diagnose ASD after the age of 7 years.

Children were diagnosed earlier in major cities compared with regional Australia. This is consistent with international research and probably the result of reduced access to health services.17,20,21 The possible earlier diagnosis of children in remote areas compared with major cities may reflect longer waiting times for specialist services in highly populated areas.22

This is the first study to investigate trends in the diagnosis of ASD in Indigenous Australians, with results indicating no difference in age at diagnosis. A smaller proportion of children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin than expected were diagnosed with AspD before age 7 years, suggesting that children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin with a less severe clinical presentation may not currently be identified early.

Children from a CALD background received a diagnosis 5 months earlier than other children. Most studies investigating age at diagnosis in ethnic minority groups have reported either no association21,23 or that children from a minority background are diagnosed later.24,25 A smaller proportion of children from a CALD background were diagnosed with AspD, which may account for the overall earlier age at diagnosis in these children.

A few limitations should be noted. The exclusion of children aged 7 years and over (in accordance with HCWAP eligibility) may have resulted in an underestimation of the age at diagnosis of ASD in Australia. The dataset only included families who registered to receive funding through the HCWAP. Although this is the most complete dataset currently available in Australia, it is possible that some cases were missed as families either chose not to register or were unaware of the HCWAP. Also, we were not able to confirm the reliability of diagnoses.

Despite these limitations, this study provides an important examination of trends in the diagnosis of ASD and suggests there may be a substantial gap between the age at which a reliable and accurate diagnosis is possible and the average age at which ASD is diagnosed in Australia. Future research should examine this gap, and investigate barriers that delay the diagnosis of ASD to ensure that families and communities can benefit from best-practice approaches to early intervention.

1 Average age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders across diagnostic groups

Diagnostic group | No. (%) of children | Mean age in months (SD)* | Median age in | ||||||||||||

Autistic disorder | 10 263 (68.1%) | 46.5 (13.6) | 45 (45–46) | ||||||||||||

Asperger's disorder | 2 164 (14.4%) | 59.5 (10.6) | 61 (60–62)† | ||||||||||||

Pervasive developmental disorder — | 2 626 (17.4%) | 51.1 (13.5) | 52 (51–53)†‡ | ||||||||||||

Autism spectrum disorder (combined group)§ | 15 074 | 49.2 (14.0) | 49 (49–49) | ||||||||||||

* Mean age in months (SD) is reported for comparison with other studies. † Significantly different from autistic disorder (P < 0.001). ‡ Significantly different from Asperger's disorder (P < 0.001). § Children with childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett's disorder are included in the total sample but are not reported by diagnostic group because of the very low frequency of these disorders. | |||||||||||||||

2 Frequency of diagnoses and proportion of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder by age group

Age group | No. of children diagnosed | Percentage (95% CI) | |||||||||||||

< 24 months | 395 | 2.6% (2.4%–2.9%) | |||||||||||||

25–36 months | 2905 | 19.3% (18.6%–19.9%) | |||||||||||||

37–48 months | 4052 | 26.9% (26.2%–27.6%) | |||||||||||||

49–60 months | 3914 | 26.0% (25.3%–26.7%) | |||||||||||||

61–72 months | 3578 | 23.7% (23.1%–24.4%) | |||||||||||||

73–84 months | 230 | 1.5% (1.3%–1.7%) | |||||||||||||

4 Frequency of and age at autism spectrum disorder diagnoses as a proportion of state population estimates

No. of children diagnosed | Age at diagnosis (months) | Case ascertainment | |||||||||||||

Cluster* | State | Median (95% CI) | Range | Population (N)† | Expected Incidence‡ | Ascertainment (95% CI) | |||||||||

1 | Western Australia | 930 | 46 (45–47) | 15–81 | 218 051 | 2 181 | 42.6% (40.3%–45.8%) | ||||||||

New South Wales | 4 735 | 47 (46–47) | 19–83 | 656 880 | 6 569 | 72.1% (70.0%–74.0%) | |||||||||

2§ | Tasmania | 335 | 49 (48–51) | 22–83 | 44 561 | 446 | 75.1% (67.0%–83.0%) | ||||||||

Victoria | 4 771 | 50 (49–50) | 15–84 | 489 659 | 4 897 | 97.4% (94.3%–99.8%) | |||||||||

South Australia | 1 076 | 50 (48–51) | 17–81 | 136 348 | 1 363 | 78.9% (74.3%–83.7%) | |||||||||

3§¶ | Australian Capital Territory | 149 | 51 (47–55) | 16–83 | 33 411 | 334 | 44.6% (37.8%–52.2%) | ||||||||

Queensland | 2 980 | 52 (51–52) | 16–83 | 425 968 | 4 260 | 70.0% (67.5%–72.5%) | |||||||||

Northern Territory | 97 | 53 (50–58) | 25–75 | 25 811 | 258 | 37.6% (30.5%–45.5%) | |||||||||

Total | 15 074 | 49 (49–49) | 15–84 | 2 030 690 | 20 307 | 74.2% (72.8%–75.2%) | |||||||||

* WA and NSW were combined for analysis as there was no statistically significant difference in the average age at diagnosis between states (P = 0.36). There were no statistically significant differences between Tas, Vic and SA (P = 0.94), or between ACT, QLD and NT (P = 0.84), with these states also grouped for analysis. † State population estimates of children aged under 7 years. ‡ Expected incidence is calculated as 1% of the population (N). § Significantly different from cluster 1 (P < 0.001). ¶ Significantly different from cluster 2 (P < 0.001). | |||||||||||||||

Received 10 March 2014, accepted 13 November 2014

- Catherine A Bent1

- Cheryl Dissanayake1

- Josephine Barbaro1

- La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC.

Catherine Bent is supported by a La Trobe University Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

No relevant disclosures

- 1. Dawson G, Jones EJ, Merkle K, et al. Early behavioral intervention is associated with normalized brain activity in young children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012; 51: 1150-1159.

- 2. Perry A, Blacklock K, Dunn Geier J. The relative importance of age and IQ as predictors of outcomes in intensive behavioral intervention. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2013; 7: 1142-1150.

- 3. Flanagan HE, Perry A, Freeman NL. Effectiveness of large-scale community-based intensive behavioral intervention: a waitlist comparison study exploring outcomes and predictors. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2012; 6: 673-682.

- 4. Guthrie W, Swineford LB, Nottke C, Wetherby AM. Early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: stability and change in clinical diagnosis and symptom presentation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013; 54: 582-590.

- 5. Johnson CP, Myers SM; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2007; 120: 1183-1215.

- 6. Daniels AM, Mandell DS. Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: a critical review. Autism 2013; 18: 583-597.

- 7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition. Washington, DC: APA, 2000.

- 8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: APA, 2013.

- 9. Barbaro J, Dissanayake C. Prospective identification of autism spectrum disorders in infancy and toddlerhood using developmental surveillance: the Social Attention and Communication Study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2010; 31: 376-385.

- 10. Veness C, Prior M, Bavin E, et al. Early indicators of autism spectrum disorders at 12 and 24 months of age: a prospective, longitudinal comparative study. Autism 2012; 16: 163-177.

- 11. Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 459-465.

- 12. Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014; 63: 1-21.

- 13. Williams K, Glasson EJ, Wray J, et al. Incidence of autism spectrum disorders in children in two Australian states. Med J Aust 2005; 182: 108-111. <MJA full text>

- 14. Nassar N, Dixon G, Bourke J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in young children: effect of changes in diagnostic practices. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38: 1245-1254.

- 15. Williams K, MacDermott S, Ridley G, et al. The prevalence of autism in Australia. Can it be established from existing data? J Paediatr Child Health 2008; 44: 504-510.

- 16. Howlin P, Moore A. Diagnosis in autism: a survey of over 1200 patients in the UK. Autism 1997; 1: 135-162.

- 17. Rice CE, Rosanoff M, Dawson G, et al. Evaluating changes in the prevalence of the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Public Health Rev 2012; 34 (2). http://www.publichealthreviews.eu/upload/pdf_files/12/00_Rice.pdf (accessed Nov 2013).

- 18. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012; 61: 1-19.

- 19. Coo H, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Lam M, et al. Correlates of age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in six Canadian regions. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2012; 32: 90-100.

- 20. Chen CY, Liu CY, Su WC, et al. Urbanicity-related variation in help-seeking and services utilization among preschool-age children with autism in Taiwan. J Autism Dev Disord 2008; 38: 489-497.

- 21. Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2005; 116: 1480-1486.

- 22. Mandell DS, Morales KH, Xie M, et al. County-level variation in the prevalence of Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2010; 40: 1241-1246.

- 23. Goin-Kochel RP, Mackintosh VH, Myers BJ. How many doctors does it take to make an autism spectrum diagnosis? Autism 2006; 10: 439-451.

- 24. Shattuck P, Durkin M, Maenner M, et al. Timing of identification among children with an autism spectrum disorder: findings from a population-based surveillance study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48: 474-483.

- 25. Valicenti-McDermott M, Hottinger K, Seijo R, Shulman L. Age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. J Pediatr 2012; 161: 554-556.

Klaus Martin Beckmann

References:

1.) J Bowlby The making and breaking of affectional bonds. I. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. An expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. The British Journal of Psychiatry Mar 1977, 130 (3) 201-210; DOI: 10.1192/bjp.130.3.201

2.)MICHAEL L. RUTTER , JANA M. KREPPNER , THOMAS G. O'CONNOR Specificity and heterogeneity in children's responses to profound institutional privation. The British Journal of Psychiatry Aug 2001, 179 (2) 97-103; DOI: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.97

3.) Website accessed on 19/04/15 https://www3.aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/child-abuse-and-neglect-statistics

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Assoc Prof Klaus Martin Beckmann

School of Medicine, Griffith University

Cheryl Dissanayake

Prof. Rutter's and others work in on the Romanian orphans showed that despite some initial similarities with ASD features, the children who suffered neglet/abuse did not meet criteria for ASD, and the ASD features present mostly resolved once the children were placed in enriched environments.

With respect to attachment and John Bowlby, much work, including my own, has shown that children with ASD are attached to their caregivers/parents, and these attachments are functionally similar to those in children without ASD.

Competing Interests:

Prof Cheryl Dissanayake

La Trobe University