This is a republished version of an article previously published in MJA Open

It is not only what a diet excludes, but what it includes, that shapes health outcomes. This article is a practical guide for doctors to help them advise patients on nutrient-rich foods, which should form the basis of all types of plant-based diets. Of the recognised types of plant-based diets (Box 1), the most widely studied is the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet.

Plant-based diets focus on fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds and grains. Some vegetarian diets also include eggs and dairy, and a few traditional (eg, Mediterranean and Asian) plant-based diets include limited amounts of meat and/or seafood.

A varied and balanced plant-based diet can provide all of the nutrients needed for good health (Box 2).2

Plant-based diets may provide health benefits compared with meat-centred diets, including reduced risks of developing chronic diseases such as obesity, heart disease, colorectal cancer and type 2 diabetes.1

Plant-based diets more closely match recommended dietary guidelines to eat plenty of fruits, vegetables, legumes and wholegrains, and to limit intakes of saturated fats and sugars.3

A 2010 national Newspoll survey of 1200 adults indicated that 70% of Australians consume some plant-based meals in the belief that eating less meat and more plant foods improves overall health (Newspoll Research, Leaders in Nutrition, May 2010, com-missioned by Sanitarium Health and Wellbeing).

A vegetarian diet does not mean just cutting out meat. Careful planning, along with knowledge of practical ideas for using a variety of plant foods, is needed to ensure nutritional requirements are met, particularly for new vegetarians or those with special needs.

Nutrients that may need more attention in a vegetarian diet include iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin B12, vitamin D and omega-3 fats. It may be beneficial to refer people to an Accredited Practising Dietitian experienced in vegetarian nutrition.

Any dietary change can increase preparation time to begin with, but cooking plant-based meals need not be more time consuming after some training and regular practice.

A minimally processed plant-based diet, with limited (if any) amounts of animal foods derived from animals lower down the food chain, provides environmental advantages over a Western-style meat-rich diet.4-6

Studies of Australian vegetarians have found that although their protein intakes are significantly lower than those of omnivores,7,8 their intakes still easily meet recommended dietary intakes (RDIs) because most omnivores eat much more protein than is required. Most plant foods contain some protein, with the best sources being legumes, soy foods (including soy milk, tofu and tempeh), nuts and seeds. Grains and vegetables also provide protein. A glossary of protein-rich plant-based foods is provided in Box 3.

As most plant foods contain limited amounts of one or more essential amino acids it was once thought certain combinations had to be eaten at the same meal to ensure sufficient essential amino acids. Research has found that strict protein combining at each meal is unnecessary, provided energy intake is adequate and a variety of plant foods are eaten over the course of a day, including legumes, wholegrains, nuts and seeds, soy products and vegetables.9 Soy protein is a complete protein as it has a Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) equivalent to that of eggwhite or dairy protein (casein).10

Vegetarian diets can contain as much or more total (non-haem) iron as mixed diets; this iron comes primarily from wholegrain breads and cereals.11,12 Iron deficiency anaemia is not more common among vegetarians, although their iron stores (serum ferritin levels) are often lower.7,12,13 Some studies have found that lower iron stores are associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases (such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes), which may partly explain the lower risk of these diseases in vegetarians.14,15

Dairy products are not the only sources of calcium in the diet. Fortified soy, rice and oat milks, unhulled tahini, Asian greens, almonds and calcium-set tofu are good sources of bioavailable calcium in non-dairy diets.16,17 Calcium needs can be met using plant foods as long as adequate amounts of these foods are consumed each day.

Vegetarian diets can be planned to supply the required levels of nutrients during pregnancy. Research shows there are no significant health differences in babies born to vegetarian mothers.18 The higher fibre content and lower energy density of many vegetarian diets may offer significant advantages, including a reduced risk of excess weight gain.19 Further, some studies suggest that a lower intake of meat and dairy products reduces the pesticide content of breast milk.20,21

Vegetarian diets are appropriate for children of all ages.2 The growth of vegetarian and vegan children is similar to that of non-vegetarian children if meals are planned well, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics22 and American Dietetic Association.2

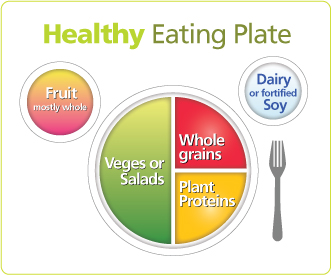

The Healthy Eating Plate device (Box 4) has been created as a visual guide for planning plant-based meals at home.

Wholegrains: these are preferred over refined grain foods (eg, brown rice instead of white rice), and can occupy about a quarter of a main meal plate. When choosing grain foods, choose those with a low glycaemic index (GI). Low GI carbohydrates help to regulate blood glucose and insulin levels, lower the levels of low-density lipoproteins and triglycerides and raise the high-density lipoprotein level, and can assist with weight management.23-25

Easy meal ideas for main plates and snacks are provided in Box 5, and Healthy Eating Plate images for main courses are shown in Box 6.

When choosing alternatives to dairy foods (eg, soy or rice milk), look for products enriched with calcium and vitamin B12.

Tofu, tempeh, Quorn (meat-free, soy-free products based on high-quality mycoprotein), textured vegetable protein, canned and frozen or chilled convenience products (eg, Sanitarium Vegie Delights, Fry’s Vegetarian foods and Syndian Natural Food Products) are available in most supermarkets.

Many varieties of legumes and wholegrains are available in Asian, Indian and health food shops.

Vegetarian cheese, dairy-free margarine/chocolate or frozen convenience meals may sound healthy, but many can hide excess kilojoules, fat, sugar or salt.

1. Enrol in a cooking class to improve your culinary skills and increase dietary variety.

5. Freeze portion-sized quantities of homemade leftover soups, stews and curries for easy lunches.

This practical paper is intended for use in patient education and may be reproduced for this purpose. Additional resources are shown in Box 7. For further details on the scientific evidence behind these recommendations please see the other articles in this supplement.

1 Types of plant-based diets1

Semi-vegetarian: includes red meat, poultry and fish less than once a week.

Pesco-vegetarian: includes fish and seafood but no red meat or chicken.

2 Sources of key nutrients in a vegetarian or vegan diet*

Wholegrains, legumes, tofu, nuts, seeds, tempeh, eggs, milk, yoghurt |

|||||||||||||||

Milk, eggs, vitamin D-fortified soy milk, vitamin D mushrooms |

|||||||||||||||

5 Some delicious plant-based meal and snack ideas

7 Resources

Free images of the Healthy Eating Plate device and sample plant-based food plates developed by the first author can be downloaded in full colour and high-resolution for educational purposes (www.sueradd.com/resources/healthyeatingplate.html).

For one-on-one dietary advice, find an Accredited Practising Dietitian with expertise in vegetarian nutrition (www.daa.asn.au).

Nutrition information, recipes, cooking classes and forums can be found at the Australian Vegetarian Society (www.veg-soc.org).

Sanitarium Health & Wellbeing Australia website (www.sanitarium.com.au) provides an abundance of free vegetarian recipes and other practical information.

Provenance: Commissioned by supplement editors; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets: what do we know of their effects on common chronic diseases? Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 1607S-1612S.

- 2. Craig WJ, Mangels AR. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc 2009; 109: 1266-1282.

- 3. Farmer B, Larson BT, Fulgoni VL 3rd, et al. A vegetarian dietary pattern as a nutrient-dense approach to weight management: an analysis of the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. J Am Diet Assoc 2011; 111: 819-827.

- 4. Carlsson-Kanyama A, Gonzalez AD. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 1704S-1709S. Epub 2009 Apr 1.

- 5. Marlow HJ, Hayes WK, Soret S, et al. Diet and the environment: does what you eat matter? Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 1699S-1703S. Epub 2009 Apr 1.

- 6. McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD, Uauy R. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet 2007; 370: 1253-1263.

- 7. Ball MJ, Bartlett MA. Dietary intake and iron status of Australian vegetarian women. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 70: 353-358.

- 8. Wilson AK, Ball MJ. Nutrient intake and iron status of Australian male vegetarians. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999; 53: 189-194.

- 9. Young VR, Pellett PL. Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 1994; 59 (5 Suppl): 1203S-1212S.

- 10. Sarwar G, McDonough FE. Evaluation of protein digestibility — corrected amino acid score method for assessing protein quality of foods. J Assoc Off Anal Chem 1990; 73: 347-356.

- 11. Davey GK, Spencer EA, Appleby PN, et al. EPIC-Oxford: lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr 2003; 6: 259-269.

- 12. Hunt JR. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78 (3 Suppl): 633S-639S.

- 13. Alexander D, Ball MJ, Mann J. Nutrient intake and haematological status of vegetarians and age–sex matched omnivores. Eur J Clin Nutr 1994; 48: 538-546.

- 14. Rajpathak SN, Crandall JP, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. The role of iron in type 2 diabetes in humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1790: 671-681. Epub 2008 May 2003.

- 15. Sun L, Franco OH, Hu FB, et al. Ferritin concentrations, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly chinese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 4690-4696. Epub 2008 Sep 16.

- 16. Weaver CM, Proulx WR, Heaney R. Choices for achieving adequate dietary calcium with a vegetarian diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 70: 543S-548S.

- 17. Weaver C, Plawecki K. Dietary calcium: adequacy of a vegetarian diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1994; 59: 1238S-1241S.

- 18. Mangels R, Messina V, Messina M. The dietitian’s guide to vegetarian diets: issues and applications. 3rd ed. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011.

- 19. Stuebe AM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Associations of diet and physical activity during pregnancy with risk for excessive gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201: 58.e1-8. Epub 2009 May 21.

- 20. Dagnelie PC, van Staveren WA, Roos AH, et al. Nutrients and contaminants in human milk from mothers on macrobiotic and omnivorous diets. Eur J Clin Nutr 1992; 46: 355-366.

- 21. Patandin S, Dagnelie PC, Mulder PG, et al. Dietary exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins from infancy until adulthood: a comparison between breast-feeding, toddler, and long-term exposure. Environ Health Perspect 1999; 107: 45-51.

- 22. Committee on Nutrition AAoP. Pediatric nutrition handbook. 6th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

- 23. Livesey G, Taylor R, Hulshof T, Howlett J. Glycemic response and health — a systematic review and meta-analysis: relations between dietary glycemic properties and health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 258S-268S.

- 24. Opperman AM, Venter CS, Oosthuizen W, et al. Meta-analysis of the health effects of using the glycaemic index in meal-planning. Br J Nutr 2004; 92: 367-381.

- 25. Thomas DE, Elliott EJ, Baur L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (3): CD005105.

We thank Anna Minko for assistance with graphic design and Greg Teschner for food photography.

Sue Radd previously consulted for Sanitarium Health and Wellbeing, sponsor of this supplement. Kate Marsh previously consulted for Nuts for Life (Horticulture Australia), who are providing a contribution towards the cost of publishing this supplement.