The Commonwealth electoral roll (ER) is the best source of representative samples of Australian adults for public health research purposes.1,2 The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 provides that ER data may be released for medical research in accordance with national privacy guidelines,3,4 on request and payment of a fee.5 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) relies on the Federal Privacy Commissioner’s definition of medical research when making decisions regarding the disclosure of elector information.6

Monash University is confident MUHREC functions in accordance with all relevant requirements.7 It is far from clear why it should be necessary to provide the AEC with evidence of the qualifications and expertise of MUHREC members, or the content of deliberations and reasons for decisions. It cannot be the AEC’s role to second-guess the university’s compliance with requirements of a third party. Nonetheless, this evidence was provided to the AEC.

Although our study satisfied the NHMRC and its peer reviewers, the AEC argued that the study did not meet its definition of medical research. The AEC uses the Australian information and privacy handbook definition of medical research,6 consistent with s 6 of the Privacy Act, which merely states that “medical research includes epidemiological research”.

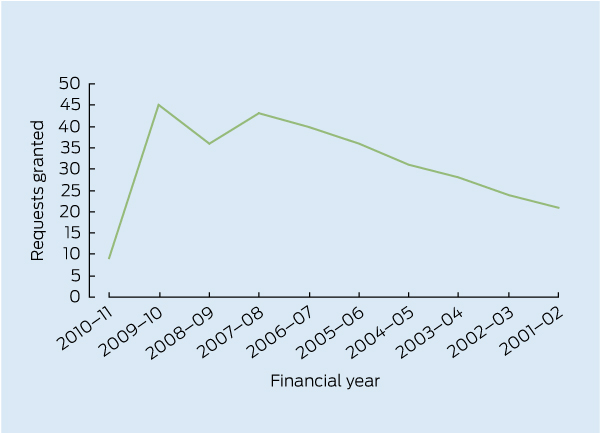

Other researchers have reported similar experiences. The AEC’s interpretation of medical research may have led to decreased numbers of researchers requesting or receiving ER data. In the 2010–11 financial year, the AEC granted nine ER extracts for medical research or health screening purposes. This represents a sharp decline from 45 recipients in 2009–10 and 36 in 2008–09. The Box shows the number of requests granted by the AEC by financial year, derived from the relevant AEC annual reports. The numbers may vary slightly because it is difficult to determine whether multiple requests have been granted for individual studies. The number of requests granted for 2010–11 is out of keeping with the general trend. The number of refusals is not recorded.

The AEC attributes the decline to a decreased number of researchers requesting extracts.2

The primary purpose of the ER is to register the entitlement to vote.2 Under paragraph 1.3 of the NHMRC privacy guidelines,8 the AEC has the discretion to decline to disclose personal information for use in medical research, even when that research has HREC approval consistent with privacy guidelines.9 Nonetheless, the AEC’s interpretation of medical research seems overly restrictive. A more transparent process is desirable.

The release of ER data for medical research should be to applicants whose research is approved by a properly established HREC whose decisions are consistent with the privacy guidelines.8 Neither HRECs nor their approvals need be reinvestigated by the AEC. The AEC is no better placed than an HREC to determine whether medical research meets requisite privacy standards. Additional privacy requirements imposed by the AEC, such as requiring third parties to execute deed polls, are acceptable but should be clearly specified and equitably applied.8

The AEC uses a purposefully narrow definition of medical research, to capture a limited range of research and subject it to enhanced privacy requirements. Concerns about its narrow scope and the need to clarify what medical research means have been discussed since 2003.10 In 2008, the Australian Law Reform Commission recommended that:

the Privacy Act be amended to provide that “research” include the compilation and analysis of statistics; and

research rules cover any human research in the public interest, not just health and medical research.11

In 2009, the Government indicated its support for the Commission’s proposed amendments.12

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Bebe Loff1

- Elissa A Campbell1

- Deborah C Glass1

- Helen L Kelsall1

- Claudia Slegers1

- Deborah R Zion1

- Ngaire J Brown2

- Lin Fritschi3

- 1 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW.

- 3 Western Australian Institute for Medical Research, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. O’Toole J, Rodrigo S, Sinclair M, Leder K. The Australian Electoral Commission Roll has good utility for “niche” household recruitment in population health studies. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009; 33: 137-139.

- 2. Australian Electoral Commission. Annual report 2010–2011. Canberra: AEC, 2011. http://www.aec.gov.au/About_AEC/Publications/Annual_Reports/2011/files/aec-annual-report-2010-2011.pdf (accessed Dec 2011).

- 3. Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 s 91A(2A)(c).

- 4. Electoral and Referendum Regulations 1940 (Cwlth) reg 9.

- 5. Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 s 90B(4), item 2.

- 6. Australian information and privacy handbook. Sydney: CCH Australia, 1998, reissued 2011: paragraph 40-040.

- 7. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, Australian Vice-Chancellors Committee. National statement on ethical conduct in human research. Canberra: Australian Government, 2009.

- 8. National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines under section 95 of the Privacy Act 1988. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2000. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/e26.pdf (accessed Mar 2013).

- 9. Australian Electoral Commission. Supply of elector information for use in medical research. 2011. http://www.aec.gov.au/Enrolling_to_vote/About_Electoral_Roll/medical_research.htm (accessed Dec 2011).

- 10. Privacy Commission. Review of the guidelines under section 95 of the Privacy Act 1988: joint summary. 2003. http://www.privacy.gov.au/materials/types/reports/view/6621 (accessed Dec 2011).

- 11. Australian Law Reform Commission. For your information: Australian privacy law and practice. ALRC report 108. Vol. 3. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008: recommendations 65-1–65-3. http://www.alrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/108_vol3.pdf (accessed Dec 2011).

- 12. Ludwig J. Enhancing national privacy protection: Australian Government first stage response to the Australian Law Reform Commission report 108 “For your information: Australian privacy law and practice”. 2009. http://www.dpmc.gov.au/privacy/alrc_docs/stage1_aus_govt_response.pdf (accessed Dec 2011).

Abstract

In the 2010–11 financial year, there was a dramatic reduction in the approvals granted by the Australian Electoral Commission for access to samples of the adult population derived from the electoral roll for the purposes of public health research.

Much time and effort has been expended in making applications without success. Researchers refused access to electoral roll samples must rely on sampling methods that are not as robust and that may produce less reliable data.

We outline a set of recommendations that, if adopted, will result in a fairer system for obtaining access to the electoral roll for public health research.