To the Editor: On 5 June 2012, the forum “Eliminating childhood lead toxicity in Australia — a little is still too much” was held at Macquarie University to examine new evidence on the toxicity of lead and its implications for Australian children and communities.

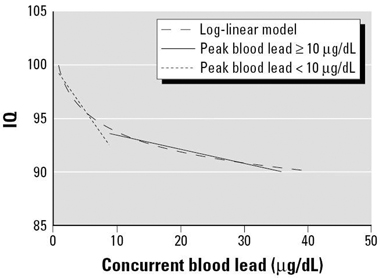

Presently, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recommends an increasingly obsolete intervention level that was established in 1993: blood lead levels of below 10 μg/dL. However, new and overwhelming evidence indicates that even levels below 5 μg/dL are associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including decreased intelligence and academic achievement, sociobehavioural problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning difficulties, oppositional and conduct disorders, and delinquency. Importantly, the greatest relative effects on IQ occur at the lower blood lead levels (Box).1

In Germany, the reference value for blood lead levels in 3–14-year-olds was lowered in 2009 to 3.5 μg/dL.2 In 2012, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eliminated the “level of concern” set previously at 10 μg/dL and established 5 μg/dL as the intervention level for individual children.3 Also in 2012, the US National Toxicology Program concluded that levels below 5 μg/dL are associated with detrimental health outcomes in children and adults.4

The potential risk of low lead exposure in Australian children can be estimated using US exposure rates and Australian population data. About 7.4% of US children aged 1–5 years have a blood lead level above 5 μg/dL. Applying this rate to Australian children aged 0–4 years suggests that about 100 000 may have blood lead levels associated with adverse health outcomes.

At the Macquarie University forum on lead toxicity, consensus was reached that the NHMRC goal should be lowered.5 To eliminate childhood lead toxicity in Australia, we need to improve ways of identifying sources of lead exposure, assessing the impacts of lead exposure, and eliminating or controlling lead risks. Relevant legislation and standards relating to health and environmental levels of lead should be revised to achieve blood lead levels below 1 μg/dL. Community involvement in implementing the necessary changes and cost–benefit analyses of interventions were also called for at the forum.

Modelling of blood lead levels in children*

* Log–linear model for concurrent blood lead concentration along with linear and log–linear models for concurrent blood lead levels among children with peak blood lead levels above and below 10 μg/dL. Reproduced with permission from Environmental Health Perspectives.1

- 1. Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 894-899.

- 2. Wilhelm M, Heinzow B, Angerer J, Schulz C. Reassessment of critical lead effects by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission results in suspension of the human biomonitoring values (HBM I and HBM II) for lead in blood of children and adults. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2010; 213: 265-269.

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC response to Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention recommendations in “Low level lead exposure harms children: a renewed call for primary prevention”. Atlanta: CDC, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/acclpp/cdc_response_lead_exposure_recs.pdf (accessed Jul 2012).

- 4. National Toxicology Program. NTP monograph on health effects of low-level lead. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/NTP/ohat/Lead/Final/MonographHealthEffectsLowLevelLead_prepublication_508.pdf (accessed Jul 2012).

- 5. Taylor MP, Winder C, Lanphear BP. Eliminating childhood lead toxicity in Australia — a little is still too much. A consensus for a way forward to eliminate lead toxicity in Australian children. http://public.mq.edu.au/public/download.jsp?id=71937 (accessed Jul 2012).

We thank the Macquarie University Centre for Legal Governance for providing financial support for the forum. Mark Taylor is the recipient of a Macquarie University Excellence in Research Award, which was also used to fund the forum. We thank the forum attendees for contributing to discussions at the meeting and to the development of a consensus statement, on which this letter is based.

No relevant disclosures.