A single entry and exit point model would be more efficient for graduates and employers alike

Completion of a structured internship is a requirement for medical graduates seeking to progress from provisional to general registration in Australia. Despite minor historical variations between states and territories, there is increasing consistency among internship programs across the country. Driving forces behind this include the establishment of a national registration and accreditation scheme,1 the development of an Australian curriculum framework for prevocational training2 and interstate collaborations in education and assessment.3 Further, the Medical Board of Australia has recently moved to develop a national registration standard for granting general registration on completion of internship.4

Work has also commenced on harmonising processes for internship allocation, which vary between jurisdictions in terms of both application and selection procedures. In 2010 and 2011, this was spearheaded by the Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils with a national audit of internship acceptances.5 The audit process was developed to minimise the number of unfilled vacancies at the start of the internship year resulting from some candidates accepting multiple jobs.

The results of the 2011 audit of internship acceptances for the 2012 clinical year were presented at the 16th Australasian Prevocational Medical Education Forum. Of 2904 applicants who accepted positions, 41% applied to multiple states and territories, and 82 applicants accepted at least two job offers. There were twice as many applicants who accepted multiple job offers in 2011 as there were in 2010.6

Given that graduate numbers are forecast to increase for several more years,7 competition for internships in popular health services will intensify. It is inevitable that prospective interns will attempt to maximise their chances of securing an internship in a preferred location, and so it follows that the number of candidates applying to multiple jurisdictions is likely to rise.

It is for these reasons that other countries have adopted various national allocation systems. In the United Kingdom, for instance, graduates apply for entry to prevocational training via the central Foundation Programme Office and nominate their preference of “foundation schools”. Candidates are ranked according to predefined criteria and then offered their highest preference of school with an available place.8 Despite obvious differences in the structure of postgraduate training, the United States also has a national system.9 Operating since 1952, the National Resident Matching Program processed 37 735 applications for 26 158 positions in 2011.10

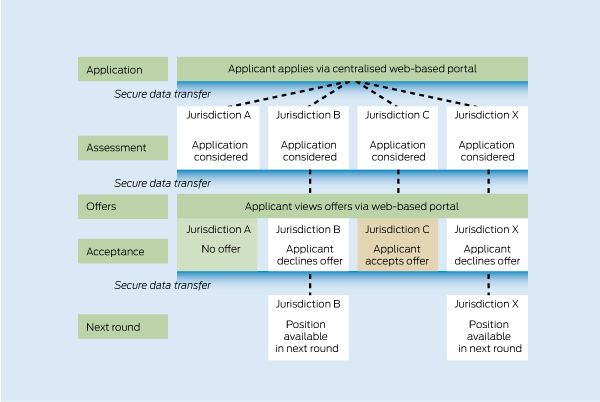

A single entry and exit point model meets all of these requirements (Box). This would involve the development of an online “shopfront” portal, managed by a national coordinating body. Applicants would submit one application based on an agreed minimum set of data, and could apply for an internship in as many, or as few, jurisdictions as they wish. Dates and timing of offers would be nationally consistent, but individual jurisdictions would retain responsibility for matching candidates to specific health services. This would require the secure transfer of selected applicant data between national and state-based back-of-house systems. Applicants would receive up to one time-limited offer per jurisdiction, but would be able to accept only a single position nationwide. Subsequent rounds of offers would follow for unmatched candidates.

For jurisdictions and health services, a national system would provide greater certainty about commencing intern numbers (as it would be impossible for a graduate to commit to multiple positions). Job acceptances would be confirmed earlier and there would be no need for annual audits. It would also provide a rich source of data about graduates and their work intentions. This has considerable value at a time when trainee numbers are increasing rapidly.7 Importantly, this particular model avoids the need for jurisdictions to agree on a uniform process for prioritising and selecting candidates.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. About the national scheme. http://www.ahpra.gov.au/~/link.aspx?_id=6DF947CD70874905AF67565732 50ADFD&_z=z (accessed Apr 2012).

- 2. Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils. Australian curriculum framework for junior doctors. http://curriculum.cpmec.org.au/ (accessed Apr 2012).

- 3. Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils. ACF resources. http://www.cpmec.org.au/index.cfm?Do=View.Page&PageID=201 (accessed Apr 2012).

- 4. Medical Board of Australia. Second round consultation on a proposed registration standard for granting general registration as a medical practitioner to Australian and New Zealand medical graduates on completion of intern training. http://www.medicalboard.gov.au/News/Past-Consultations/2011/Consultation-November-2011.aspx (accessed Apr 2012).

- 5. Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils and Clinical Education and Training Institute. External report on the outcome of the National Audit of Internship Acceptances Pilot Project — clinical year 2011. http://www.cpmec.org.au/files/externalreportontheoutcomeofthenational auditofinternshipclinicalyear2011.pdf (accessed Jan 2012).

- 6. Roberts-Thomson R, Campbell K, Peterson D, Thompson G. A national approach to supporting the increase in medical graduate numbers. Presented at the 16th Australasian Prevocational Medical Education Forum; 2011 Nov 6-9; Auckland, New Zealand.

- 7. Department of Health and Ageing. Medical Training Review Panel: fourteenth report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2011. http://www.health.gov. au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/work-pubs-mtrp-14 (accessed Jan 2012).

- 8. The Foundation Programme. How to apply. http://www.foundation programme.nhs.uk/pages/home/how-to-apply (accessed Apr 2012).

- 9. National Resident Matching Program. Main residency match. http://www. nrmp.org/res_match/index.html (accessed Apr 2012).

- 10. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: 2011 main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/data/resultsanddata2011.pdf (accessed Apr 2012).

We acknowledge the input of the members and secretariat of the Australian Medical Association Council of Doctors-in-Training (AMACDT) to the development of the AMA Position Statement on National Intern Allocation (available at http://www.ama.com.au/dit).

All authors are former members of AMACDT. Rob Mitchell represents the AMACDT on advisory committees of the Department of Health and Ageing and Health Workforce Australia. Rick Fielke formerly represented the AMACDT on the Confederation of Postgraduate Medical Education Councils National Intern Allocation Working Party. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors.