“The girls don’t drink much; ’bout the same as the fellas”

As I have reported earlier,1 I believe that the historical and political background and the cultural aspects of drinking have been insufficiently considered. There is an entrenched expectation of Aboriginal community members that to drink is an expression of identity and culture.

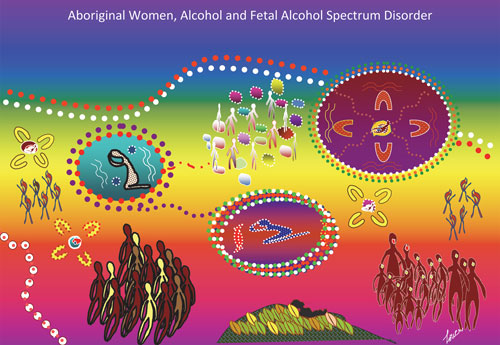

Some years ago, with input from a number of Aboriginal community members, I constructed a framework to assist in understanding the development of identity and the resulting changes of emotions and physical boundaries across the lifespan.2

Using this framework, I have proposed an expanded view on the use of alcohol in Indigenous communities,2 formulated through interviews and discussions with members of remote, rural and urban Aboriginal communities in Queensland. This was originally done in the context of trying to better understand fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and early life trauma.

For many Aboriginal women, alcohol, like pregnancy, is a normal part of the life cycle.

My proposed life cycle framework or model broadens the Western approach and integrates with cultural constructionist theories to give a clearer understanding of alcohol use.2

It is during the ages of 3–5 years that children begin to retain strong memories that continue to provide background to their emotions in later life. Generally, children develop responsibility for self-sufficiency between the ages of 3 and 5. An important aspect of this is the development of trust. Trust in adults and their ability to ensure one’s safety in a crisis is the earliest form of faith. If caregivers are inconsistent in satisfying a child’s needs, the child will not develop this sense of trust, faith and hope.3

When one is a tiny little boy and is sent to bed by his mumma, who is drinking noisily in the next room where the music is loud, then suddenly, all becomes very quiet and still. You pull the blankets up over your head and lie very still because you become really scared. Too scared to move. You lay there thinking “Is the bogeyman’s gunna come an get me?” You call out to your mumma and dadda but there is no answer. You suddenly realise that you are all alone in the house. Thoughts wander through your little mind, wondering where is mumma and dadda? Where are they? Why don’t they hear my call? They must know I am scared? What should I do now? Should I stay here or should I try and run to find my nanna’s or auntie’s place? It is very dark outside. I awake to hear a very loud crash and yelling — people fighting. My uncle then comes in and carries me over to my nanna’s house. Here I know that I am safe. There is no reason to be scared anymore.1

Interviewees reported feeling alone as a child, even when surrounded by adults drinking and partying, resulting in the child feeling unimportant as an individual. As these children grew older, they told of becoming more dependent on friends and peers for acceptance; their behaviour mimicking that of the adults around them and the peers for whose attention they aspired. Sometimes they reported an extraordinary sense of isolation related to what they perceived as a breakdown of their cultural identity, as well as the lack of mutual respect between older and younger community members, creating a sense of shame.

As a child who lived in a home where there is lots of violence, bashings and too much grog, because I was the bigger kid I used to get all the smaller kids in a room and we would lock the door and go into the corner and huddle together, we would cover our ears and cry and I would rock to try and silence the noise and screams from my mum asking my dad to stop. I am now in my early twenties and I don’t rock anymore. Loud noises still frighten us kids; we were so scared, so very, very scared. Why did our mum and dad do this to us? We had no one to come and take us away to somewhere safe; it was like nobody cared.2

You go to bed quivering with fear and listening to drunks all night. You wake up and there are drunks everywhere, sleeping all around, and some still drinking. You search for food to fill your empty belly before you go to school. Most times there is none. Usually you go to school with an empty belly. You feel tired and you get a pain in your belly from lack of food. You become shy and embarrassed and begin to isolate yourself from others, especially those who have food. You run home at lunchtime hoping that there is some food waiting, but there is never any. When you come home from school, there are drunks still there. You go to bed and the drunks are still there — same old cycle. Eventually, after being exposed to alcohol year after year, you give up and join in, fill your empty belly with grog and become a drunk too.1

She may have been raped. Especially being young girls, they’re trying to heal their own problems. So they look for the first person to come along, looking for good faces. They drink beers an’ wine, it is cheaper. Except when they really want to party out and look for a man, they get spirits. They get pregnant and then they forget to stop drinking. They have money problems, which leads to drinking, which leads to pregnancy, which leads to pension, which leads to drinking, which leads to more problems, which leads to more drinking, which leads to more pregnancies — then they can’t look after their kids.1

I don’t think they know if anything can happen to the baby. Something might happen when they drink if they are pregnant. Drinking alcohol is a way women try to kill their babies. Some young women get drunk and even try to commit suicide, not just because they are pregnant — there is other abuse too. The person drinks alcohol — becoming angry — and then picks a fight with another woman or a man and becomes involved in a fight — killing the baby one time.1

Provenance: Not commissioned; not externally peer reviewed. This essay was an entrant in the 2011 Dr Ross Ingram Memorial Essay Competition. It is adapted from an article published in the Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal.<a href="#0_CHDFIEFA" class="SupXRef">1</a> Quotes are reproduced with permission

- Lorian G Hayes1

- Centre for Chronic Disease, School of Medicine, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.