Headache, particularly migraine, is the commonest neurological problem with which patients present to general practitioners and neurologists. Comprehensive history-taking offers the best chance of establishing whether a headache is primary (idiopathic) or secondary to an underlying condition. Most headaches encountered in practice are primary, either migraine headache or tension-type headache. Less common primary headaches include cluster headache, primary cough and exertional headache, primary sex headache and primary thunderclap headache. The second edition of The international classification of headache disorders provides a comprehensive description of the many types of headache.1

Important features in the patient history are: location, temporal pattern and quality of the pain; presence of associated symptoms; and presence of specific triggers (eg, exertion, coughing, sneezing). Red flags that may indicate a secondary headache are summarised by the mnemonic SNOOP4 (Box 1).2 When any of these red flags are present, brain imaging is mandatory (computed tomography or magnetic resonance, depending on how or when the patient presents, resource availability and clinical urgency). However, for most patients with migraine, brain imaging is not necessary.

Migraine headache is defined by the features of the headache and the presence of associated symptoms (Box 2).1 Migraine is considered a primary disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). It is a chronic disorder with episodic manifestations, and it is often familial and has a strong genetic component. Episodic migraine affects up to 18% of women and 6% of men.

The manifestations of migraine are believed to be due to increased cortical neuronal excitability, owing to defective modulatory pathways in the brainstem and possibly other structures in the CNS. In particular, the aura of migraine is not due to vasospasm — it is due to altered neuronal activity called “cortical spreading depression”.3-5

For Rachel, the other features of her attacks that make the diagnosis of migraine definite are the change in sides of both the headache and aura. In addition to the headache phase, there are often premonitory and resolution phases.3,6 In some patients with migraine, nausea and vomiting are the most disabling features; in others, it is the aura or the severity of the headache.

Acute migraine attacks can be severely disabling, and chronic migraine is even more disabling. The World Health Organization ranks migraine as 19th worldwide of all the causes of years lived with a disability due to a medical condition and eighth of the mental and neurological disorders in terms of disability. In high-income countries such as Australia, the total disability due to migraine is said to be more than 1.5 times that due to multiple sclerosis and Parkinson disease combined and almost three times that due to epilepsy.7 However, it is considerably under-recognised, underdiagnosed and undertreated worldwide.

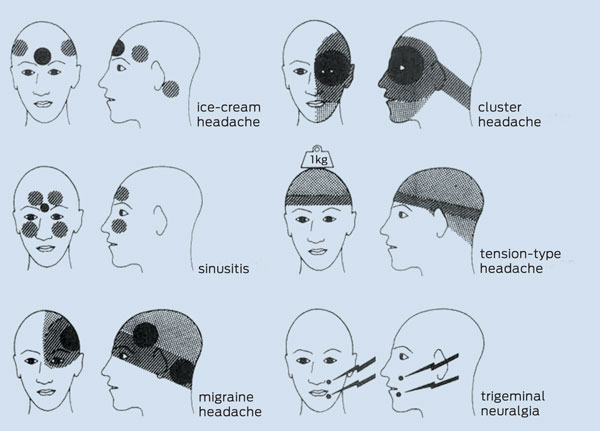

The locations of migraine headache and other types of primary and secondary headaches are shown in Box 3.

It is important to distinguish migraine headache from cluster headache, as the approaches to management differ significantly. Cluster headache is one of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias,1 which are characterised by strictly unilateral headaches with autonomic features. It is differentiated from migraine by the duration and frequency of attacks. Cluster headache has such a dramatic presentation, and the headache is so excruciating, that it should never be missed. Patients can have up to eight attacks per day, with attacks lasting 15–180 minutes each. Nocturnal attacks that wake the patient are common. The patient is usually agitated and will pace about (in contrast to migraine, where the patient will lie still). Cluster headache is accompanied by redness or tearing of the eye, drooping of the eyelid and constriction of the pupil (Horner syndrome) on the ipsilateral side, and blockage or running of the nostril (autonomic features) on the ipsilateral side. Management of cluster headaches includes inhaled oxygen (100%, 12 L/minute, 15 minutes, grade A evidence)8 or acute sumatriptan therapy (6 mg, subcutaneous injection, grade A evidence), and oral verapamil for prophylaxis (grade A evidence).9

Migraine aura, which is almost always (in more than 95% of cases) visual but sometimes involves other senses or speech, occurs in up to 30% of patients with migraine (Box 4).1 True weakness does not occur in typical migraine with aura, but may occur in hemiplegic migraine and basilar-type migraine, which are very rare.1

Patients who suffer migraine with aura can go on to have visual aura without headache in later years. Also, migraine aura without headache can occur for the first time in later life — the so called transient migrainous accompaniments.4 Such symptoms must firstly be considered as possibly being due to another neurological problem, such as a transient ischaemic attack or giant cell arteritis. Hence, patients with strictly unilateral headaches and contralateral aura, atypical aura, or first visual or other neurological disturbance with or without headache at over 50 years of age should be referred to a neurologist for urgent assessment and brain imaging, preferably with magnetic resonance imaging.

Chronic migraine is diagnosed when a patient known to have migraine without aura has headaches on 15 or more days per month for at least 3 months, of which eight or more per month meet the criteria for migraine without aura or respond to migraine-specific acute medication (triptans or ergot preparations).10 Its prevalence is 2% worldwide11 and patients with chronic migraine are more disabled, have a lower quality of life, have a higher rate of psychiatric comorbidity and use significantly more health care resources than patients with episodic migraine.12 About 2.5% of patients with episodic migraine will progress to chronic migraine over a year. Risk factors for progression include female sex, lower socioeconomic status and increased caffeine intake.11 Medication overuse is also an important contributor to development of chronic migraine.

MOH is likely in patients who have headache on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, have been using acute medication therapies frequently and have had worsening of the headaches while using the acute medication.13 Frequent use of ergot preparations, opiates, triptans or combination analgesics is defined as 10 or more days per month and for simple analgesics 15 or more days per month. Many patients with MOH have daily headaches and take acute medication every day or nearly every day.

The risk of stroke is increased in patients with migraine. According to a recent meta-analysis, there is a twofold increased risk of ischaemic stroke which occurs in patients with migraine with aura but not in patients with migraine without aura.14 Women are more at risk, particularly if they are young (under 45 years), smokers and taking the oral contraceptive pill. The overall absolute risk is, however, quite low, and stroke in young patients with migraine is rare.15

Rachel has migraine with aura, nocturnal severe migraine and other headaches of the tension type. Because of her frequent use of NSAIDs, the possibility of MOH was discussed and she was asked to start keeping a simple headache diary. For daytime attacks with aura, she was asked to take diclofenac potassium 50 mg tablets with domperidone 10–30 mg at the onset of her aura or as soon as she developed a migraine headache without aura. If she went on to develop a headache despite taking diclofenac at the onset of aura, she was to repeat the dose of diclofenac. She was encouraged to avoid using anything for milder headaches. For nocturnal attacks, she was asked to try ondansetron wafers and an indomethacin suppository (as oral therapy was futile).

Patients with episodic migraine need to be given an explanation of the condition and a treatment plan, and the treatment goals need to be discussed. Online resources for patients are available from Headache Australia (http://headacheaustralia.org.au, see the iManage Migraine app), the World Headache Alliance (http://www.w-h-a.org) and the BMJ (http://www.bmj.com/multimedia/video/2011/02/05/migraine-pain-and-pressure). Treatment options for complicating factors are shown in Box 5.

Identifying triggers: The commonest triggers in migraine without aura are stress, foods (eg, alcohol, chocolate, dairy foods [particularly cheese]) and menstruation.6 In migraine with aura, a visual stimulus (eg, flickering light) is a common trigger. Triggers should generally be avoided, although an alternative behavioural approach of trying to cope with some triggers has been suggested.19 However, many patients cannot identify triggers, and some triggers may be complex (eg, a period of stress coinciding with menstruation). Only about 10% of women with migraine have pure menstrual migraine, where they only have attacks during menstruation.

Acute treatment: It is important to tailor the acute treatment to both the individual patient and to the different attacks experienced by the individual patient. Acute medication therapies in migraine are either non-specific (paracetamol, aspirin or other NSAIDs) or migraine-specific (ergot preparations and triptans) (Box 6). Initial treatment should be with simple analgesics and NSAIDs, taken at the earliest possible time (at onset of aura, if present). Suppositories can be helpful in patients with significant nausea or those who are already vomiting.

Antiemetic and prokinetic drugs are helpful in treating associated nausea and may improve the efficacy of analgesics, NSAIDs and triptans by overcoming associated gastroparesis. Antiemetics may also reduce the severity of the headache and should always be used if there is nausea. Local guidelines list oral domperidone 10–20 mg (grade B evidence), metoclopramide 10–20 mg (grade B evidence) and prochlorperazine 10 mg, and prochlorperazine 25 mg suppositories.17 Domperidone is much less likely than metoclopramide or prochlorperazine to cause a dystonic reaction or akathisia. Although only PBS listed for cytotoxic chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, ondansetron wafers are often the most effective antiemetic for some patients; however, cost is an issue.

Emerging treatments: With new treatments emerging, this is an exciting time in the field of migraine management. On the horizon are new classes of non-vasoconstrictor drugs, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists (“gepants”) and serotonin 1F receptor agonists, as well as novel neuromodulation techniques such as occipital nerve stimulators and transcranial magnetic stimulation.20

Status migrainosus is a debilitating migraine attack that lasts more than 72 hours and is refractory to the patient’s usual treatments.1 Hospital admission and treatment of dehydration with intravenous fluids are usually necessary. Parenteral administration of DHE, with an antiemetic, can be effective in this situation. Some guidelines suggest using 8-hourly intravenous injections of 0.25–1 mg DHE.17 However, in our experience, it is better tolerated as an infusion of 3 mg DHE over 24 hours (which can be titrated up or down according to response and adverse effects). Other options include parenteral chlorpromazine, droperidol, prochlorperazine and sumatriptan.17

Patients who have three or more migraine attacks per month are usually considered as being suitable for prophylaxis. However, prophylaxis may also be warranted in patients who have fewer attacks — for example, if the attacks last days, do not respond to acute treatment, cause lost work time or are otherwise disabling. Conversely, patients who have more than three attacks per month that are all reliably aborted by acute treatment may not need prophylaxis. The aim of prophylactic treatment is not only to reduce the frequency of attacks but also to reduce severity and duration of the attacks and to render the attacks more amenable to acute treatment. The initial choice of prophylactic agent is usually based on side-effect profiles and patient characteristics. First-line prophylactic agents are serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as amitriptyline, other tricyclic antidepressants, 5-HT2-receptor antagonists (pizotifen) and β-blockers (propranolol and metoprolol) (Box 7).17,21-23 The β-blockers, however, are best avoided in patients who have frequent migraine with aura as they can worsen the aura.

Fact or fiction?

FACT: It is true that the risk of stroke is increased in patients who suffer migraine with aura.

In some patients with chronic migraine, the condition responds to treatment with topiramate11 or repeated injection of onabotulinumtoxinA into multiple sites in the head and neck.24 A multidisciplinary approach, including behavioural pain management, to chronic migraine and other refractory headaches (eg, in a dedicated headache clinic) is more likely to be successful than other approaches.25

Rachel returned 2 months later with her diary. Overall, she felt that there had been some improvement. According to her diary, she had had 17 headache days, more than she thought she was having before keeping the diary. Some of her less severe headaches resolved without treatment, which surprised her. She had had three daytime-onset migraine attacks with aura, two of which responded to diclofenac and domperidone. She had had two full-blown nocturnal-onset attacks, one of which occurred during her period; the attack during her period did not respond to ondansetron and indomethacin but the other did, and this was the first time she had ever been able to abort a full-blown attack. However, she had put on more weight despite taking only a low dose of amitriptyline.

1 SNOOP4 — headache red flags*1

Systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss) or secondary risk factors (HIV, cancer)

Neurological symptoms or abnormal signs (confusion, impaired alertness or consciousness)

Onset — sudden, abrupt or split second (“thunderclap”)

Older — new onset or progressive headache, especially in patients older than 50 years (giant cell arteritis)

Previous headache history — first headache or different headache (change in attack frequency, severity or clinical features)

Postural or positional aggravation

Precipitated by a Valsalva manoeuvre or exertion

Papilloedema

2 Diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura

At least five attacks

Headaches last 4–72 hours

At least two of the following headache characteristics:

unilateral

pulsating

moderate to severe pain

aggravated by, or causes avoidance of, routine physical activity

At least one of the following during headaches:

nausea and/or vomiting

photophobia and phonophobia

4 Diagnostic criteria for migraine with typical aura4

At least two attacks

One or more fully reversible aura symptoms indicating focal cortical and/or brainstem dysfunction, such as flickering lights or loss of vision, and unilateral pins and needles or numbness

No aura symptom lasts longer than 60 minutes

Headache follows aura with a headache-free interval of less than 60 minutes

5 Complicating issues and treatment options

Frequent recurrence after initial relief of headache: consider an ergot preparation, naratriptan (as the incidence of recurrence is lower than for other triptans) or a triptan with a long-acting NSAID16

Severe perimenstrual attacks: consider perimenstrual pre-emptive treatment (eg, ergot preparation or NSAID therapy) (need diary) or prophylaxis, as menstrually related attacks are often severe and refractory to acute treatment16, 17

Intolerance to, failure of, or reticence to use, pharmacological treatments: consider non-pharmacological approaches (eg, behavioural treatment and acupuncture)16,18,19

Medication overuse headache: identify and manage (see main text)

Comorbidities (eg, depression): identify and manage

6 Recommended drugs for the acute treatment of migraine

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Alessandro S Zagami1,2

- Sian L Goddard1

- 1 Institute of Neurological Sciences, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Prince of Wales Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW.

Alessandro Zagami receives financial support from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Brain Foundation.

- 1. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-II. http://ihs-classification.org/en (accessed Feb 2012).

- 2. Lipton RB, Silberstein SD, Dodick DW. Overview of diagnosis and classification. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, editors. Wolff's headache and other head pain. 8th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008: 29-43.

- 3. Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet 2004; 363: 381-391.

- 4. Lance JW, Goadsby PJ. Mechanism and management of headache. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

- 5. Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of migraine. Neurologic Clinics 2009; 27: 335-360.

- 6. Zagami AS, Bahra A. Symptomatology of migraines without aura. In: Olesen J, Goadsby PJ, Ramadan NM, et al, editors. The headaches. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Williams, 2006: 399-405.

- 7. Collins PY, Patel V. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature 2011; 475: 27-30.

- 8. Cohen AS, Burns B, Goadsby PJ. High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009; 302: 2451-2457.

- 9. May A, Leone M, Afra J, et al. EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13: 1066-1077.

- 10. Olesen J, Bousser M-G, Diener H-C, et al. New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 742-746.

- 11. Vargas BB, Dodick DW. The face of chronic migraine: epidemiology, demographics, and treatment strategies. Neurol Clin 2009; 27: 467-479.

- 12. Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 301-315.

- 13. Silberstein SD, Olesen J, Bousser M-G, et al. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition (ICDH-II) — revision of criteria for 8.2 Medication-overuse headache. Cephalalgia 2005; 25: 460-465.

- 14. Schurks M, Rist P, Bigal M, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009; 339: b3914.

- 15. Kurth T, Chabrait H, Bousser M-G. Migraine and stroke: a complex association with clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 92-100.

- 16. Goadsby PJ, Sprenger T. Current practice and future directions in the prevention and acute management of migraine. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 285-298.

- 17. Neurology Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: neurology. Version 4. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines, 2011: 1-264.

- 18. Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Alternative headache treatments: neutraceuticals, behavioural and physical treatments. Headache 2011; 51: 469-483.

- 19. Martin PR, MacLeod C. Behavioral management of headache triggers: avoidance of triggers is an inadequate strategy. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29: 483-495.

- 20. Magis D, Schoenen J. Treatment of migraine: update on new therapies. Curr Opin Neurol 2011; 24: 203-210.

- 21. Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine-revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2009; 16: 968-981.

- 22. Stark RJ, Stark CD. Migraine prophylaxis. Med J Aust 2008; 189: 283-288. <MJA full text>

- 23. Fenstermacher N, Levin M, Ward T. Pharmacological prevention of migraine. BMJ 2011; 342: d583.

- 24. Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2011; 51: 1358-1373.

- 25. Diener H-C, Gaul C, Jensen R, et al. Integrated headache care. Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 1039-1047.

Abstract

Headache, particularly migraine, is the commonest neurological problem with which patients present to general practitioners and neurologists. Episodic migraine affects up to 18% of women and 6% of men.

Acute migraine attacks can be severely disabling and chronic migraine is even more disabling. Of the mental and neurological disorders, migraine ranks eighth worldwide in terms of disability.

Migraine is one of the primary headaches and may occur with or without aura. Differentiation from other severe primary headaches, such as cluster headache, is important for management.

The vast majority of patients with migraine can be satisfactorily helped and treated. This involves acute and prophylactic drug therapy and management of triggers.

In patients with migraine, medication overuse headache and chronic migraine need to be identified and treated.