Specialists in geriatric medicine are in short supply. Many large and medium-sized hospitals operate post-acute units for rehabilitation or extended assessment of older patients.1 These units require input from specialist geriatricians. In Australia, outside major cities, there are often no geriatricians available to support such programs.

Telemedicine, in the form of videoconferencing, provides an opportunity for specialists to interact directly with both patients and multidisciplinary teams. In a few subspecialties, mobile videoconferencing (in which the specialist interacts directly with patients, house doctors and nurses at the bedside)2,3 has been used as a substitute for “traditional” ward rounds.

The geriatric unit operates as a post-acute service. Patients are identified for admission within a few days of entry to the hospital through a combination of screening and referral.4 This pre-transfer process includes an online assessment performed by a geriatrician using a web-based clinical decision support system based on the interRAI Acute Care assessment system.5,6

A shared care arrangement is used, with the initial treating medical team continuing to manage medical aspects of the patients’ care. The geriatrician provides additional diagnostic input and oversees functional and psychosocial interventions as well as discharge planning. The model is thus a variation of the Acute Care of the Elderly model described by Palmer and colleagues.7,8

Weekly rounds are conducted by videoconference (VC). The web-based clinical support system enables the remote clinician to have accurate clinical information, particularly with reference to geriatric syndromes and functional and psychosocial problems. Pathology results can be viewed online. The geriatrician is able to view all of this information at his or her office desk alongside the VC monitor (Box 1).

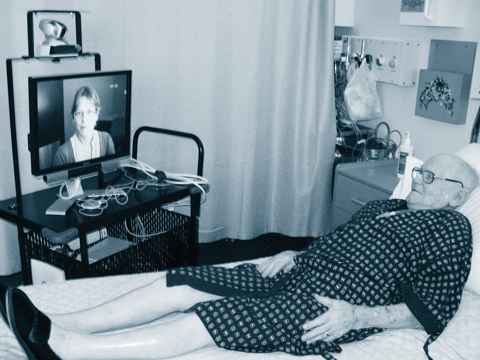

The apparatus is wheeled to the bedside and, after a brief introduction by the nurse on site, the conversation and examinations are led by the remote clinician (Box 2). Typically, there is a discussion with the nurse and house doctor; a review of pathology and imaging; a patient interview and clinical examination, including a gait and balance examination; a review of the medication chart; and a final discussion.

Travel by road to and from the hospital was about 200 minutes for the round trip. Therefore, including travel time, ward rounds and team meetings, in-person consultations with patients required a total weekly time allocation of around 8.5 hours, while the VC approach required 5.0 hours when breaks and disruptions were included. This resulted in a time difference of 3.5 hours, largely attributable to travel time. Cost analyses for VC ward rounds compared with in-person ward rounds are shown in Box 3.

The results of a sensitivity analysis of the effect of “low” and “high” input costs on the cost difference between VC and in-person consultations are summarised in Box 4.

The effects of varying the travel distance and cost per kilometre travelled, while holding all other aspects of the model constant, are summarised in Box 5. At the cost per kilometre identified in the base case ($2.75/km), videoconferencing (at a level of 5 hours per week) becomes cost-saving when the round trip is 125 km or longer. At a low-estimate cost of $1.25/km, videoconferencing becomes cost-saving if the total distance travelled for each visit exceeds 275 km. At a high-estimate cost of $4.25/km, videoconferencing becomes cost-saving when the total distance travelled each week is 81 km or more.

To our knowledge, the model of service delivery described here is unique in geriatric medical practice. Reviews in the literature suggest that patient acceptance of telemedicine is generally high,9,10 but no previous studies in a geriatric population have been reported. As the prevalence of cognitive, visual and communication deficits in this population is high, it is important to specifically verify acceptance. Our study indicated a high level of patient acceptance.

The videoconferencing model limits the ability to perform a “hands on” clinical examination. Although there is evidence that cognitive assessment and neurological examination can be performed reliably by VC,11 the geriatrician is reliant on the judgement of others for examinations requiring palpation and auscultation. The potential loss of accuracy in these areas of assessment in geriatric practice requires further research. Nevertheless, in many communities, a telemedicine service will be the only viable means of having access to the expertise of a geriatrician. Thus, the key research question is whether a telemedicine-delivered service is better than no service.

3 Cost comparison (in dollars per annum) between ward rounds conducted by videoconference (VC) and in person in the geriatric unit at Toowoomba Base Hospital

- Leonard C Gray1

- Olivia R Wright1

- Alison J Cutler2

- Paul A Scuffham3

- Richard Wootton1,4

- 1 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 Ipswich Hospital, Ipswich, QLD.

- 3 School of Medicine, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD.

- 4 Scottish Centre for Telehealth, Aberdeen, Scotland.

The Princess Alexandra Hospital Private Practice Fund provided funding for the evaluation. Queensland Health and Toowoomba Base Hospital provided funds to operate the service. Special thanks to Jillian Richardson, Nurse Unit Manager, and Susanne Pearce, Nurse Assessor, who contributed to the operational design of the service, and George Leaper, the medical student who administered the patient satisfaction survey.

None identified.

- 1. Gray L, Moore K, Smith R, Dorevitch M. Supply of inpatient geriatric medical services in Australia. Intern Med J 2007; 37: 270-273.

- 2. Smith A, Coulthard M, Clark R, et al. Wireless telemedicine for the delivery of specialist paediatric services to the bedside. J Telemed Telecare 2005; 11 Suppl 2: S81-S85.

- 3. Smith AC, Gray LC. Telemedicine across the ages. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 15-19. <MJA full text>

- 4. Gray L, Wootton R. Comprehensive geriatric assessment “online”. Australas J Ageing 2008; 27: 205-208.

- 5. Gray L, Bernabei R, Berg K, et al. Standardizing assessment of elderly people in acute care: the interRAI Acute Care instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 536-541.

- 6. Gray LC, Berg K, Fries BE, et al. Sharing clinical information across care settings: the birth of an integrated assessment system. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 71.

- 7. Palmer RM, Counsell S, Landefeld CS. Clinical intervention trials: the ACE unit. Clin Geriatr Med 1998; 14: 831-849.

- 8. Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1572-1581.

- 9. Mair F, Whitten P. Systematic review of studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ 2000; 320: 1517-1520.

- 10. Whitten P, Love B. Patient and provider satisfaction with the use of telemedicine: overview and rationale for cautious enthusiasm. J Postgrad Med 2005; 51: 294-300.

- 11. Craig JJ, McConville JP, Patterson VH, Wootton R. Neurological examination is possible using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 1999; 5: 177-181.

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the acceptance and cost of a ward-based geriatric consultation service delivered via a mobile videoconferencing system.

Design and setting: Prospective observational study conducted in the geriatric unit of Toowoomba Base Hospital, Queensland, comparing a specialist consultation service delivered by videoconference (VC) with a “traditional” in-person service. The VC system was established in January 2007 and evaluated over an 18-month period. Patient satisfaction with the service was assessed by questionnaire during a 1-week period in September 2008.

Main outcome measures: Hospital acceptance of the service; patient satisfaction with the service; comparative cost of providing in-person and VC-mediated consultations.

Results: Uptake of the service increased progressively throughout the study period. Patient acceptance levels were high. The cost of video consultations for a 12-patient ward round and case conference was less than the cost of in-person consultations if the total road distance travelled by the specialist (Brisbane to Toowoomba and back) was 125 km or longer.

Conclusion: Consultations via VC are an acceptable alternative to in-person consultations, and are less expensive than in-person consultations for even modest distances travelled by the clinician.