The residential aged-care sector is often overlooked when patient safety issues are considered. This is exemplified by the paucity of literature about clinical handover between aged-care homes (ACHs) and hospitals.1-3 Residents of ACHs are elderly, usually frail, and almost always have complex care needs. They often need to go to hospital — usually at short notice to an emergency department (ED), but also for planned admissions or to attend outpatient appointments. The transfer of ACH residents between ACHs and the acute sector involves a number of clinical handovers (between ACH staff, and between ambulance officers [AOs] and hospital staff) and a number of communication modalities (face-to-face, via telephone, by documents and — occasionally, but probably increasingly — electronically). The multiplicity of factors generates a high risk of communication failure and unsafe clinical handover, which can have a direct impact on the continuity of care and health outcomes for this population.3,4

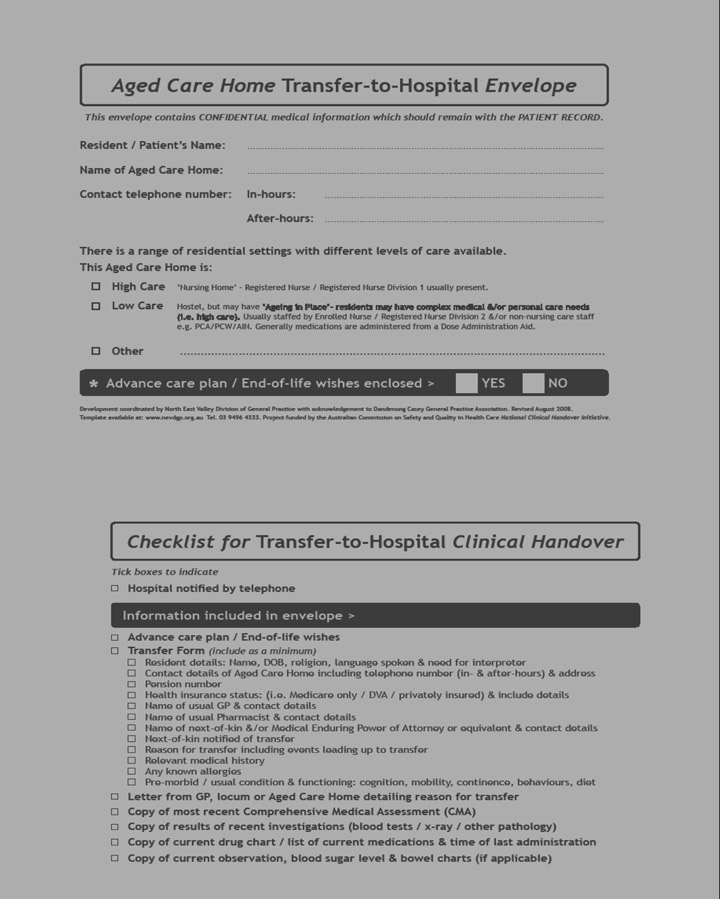

As part of the Aged Care General Practitioner Panels Initiative (ACGPPI),5 we developed an “Aged care home transfer-to-hospital envelope” (the Envelope) (Box 1) in response to frequent anecdotal reports from ACH and ED staff about the poor quality of transfer and discharge information (clinical handover) accompanying residents both to and from hospital. We identified several reasons why clinical handover was frequently so poor between these health care settings.6 Firstly, there is limited understanding of the range of constraints affecting the provision of care in each setting. Secondly, there are workforce issues that have a direct impact on both reasons for transfer to hospital and the provision of clinical handover. These include limited access to timely and regular medical care, the skills mix of the residential aged-care workforce, and frequent turnover of staff in both ACH and ED settings (recruitment and retention issues as well as shift-to-shift and staff rotation issues). Thirdly, ACH staff frequently reported that clinical and other handover information they had provided did not reach the ED but disappeared into a so-called “black hole”. In addition, we commonly had the impression, from discussions with both ACH and ED staff, that clinical handover was not really recognised as necessary. There was a sense that, once the resident/patient was “sent off”, the responsibility for care was discharged and that “they” (ED or ACH staff, respectively) would take over effective care (without awareness of the need to provide handover information).

The North East Valley Division of General Practice was the lead agency in the trial, which was conducted by a consortium of seven Divisions of General Practice. The management structure for the trial consisted of a project team, a management group and a reference group (Box 2).

The trial was conducted from September 2007 to October 2008 in three phases:

Evaluation and reporting (May to October). Evaluation methods used were:

Written surveys completed by ACH staff (165);

Semi-structured, face-to-face targeted interviews with ACH staff (19);

Semi-structured, face-to-face targeted interviews with ED staff (10 staff in three EDs);

Group interviews with ED staff (12 staff in two EDs);

Discussion group with ED staff, each completing an interview proforma (8 staff in one ED);

Semi-structured, face-to-face opportunistic interviews with AOs (11 in total, of which seven were familiar with the Envelope); and

Feedback and consultation with the management group and reference group.

The final report was lodged with the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care in October 2008.6

Almost all the ACH staff surveyed (163/165 [99%]) indicated that the Envelope was useful (Box 3), and 148/165 (90%) thought it was easy to use.

An envelope is a low-cost, familiar, age-old communication tool and the instructions on the Envelope we designed and refined are simple and clear. The Envelope can function as a stand-alone tool, requiring minimal support and training for its implementation and use. The key challenges for ongoing and wider use of the Envelope are about supply and distribution (Box 4).

2 Management structure of the Envelope trial

4 Access to and supply of the Envelope

Free website access: A template will be available on the website of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au) and the North East Valley Division of General Practice (http://www.nevdgp.org.au)

Commercial printing and distribution: The Envelope is available for purchase from Compact Business Systems (http://www.compact.com.au)

- Mary K Belfrage1

- Clare Chiminello2

- Diana Cooper3

- Sally Douglas4

- Trial Project Team, North East Valley Division of General Practice, Melbourne, VIC.

The Envelope was developed under the Aged Care GP Panels Initiative (2004–2008), funded by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing. The project was coordinated by the North East Valley Division of General Practice, with acknowledgement to Dandenong Casey General Practice Association for the original idea of a dedicated ACH-to-hospital transfer envelope. The Envelope trial was funded by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing through the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s National Clinical Handover Initiative. We acknowledge the contribution of our partner Divisions of General Practice: Impetus, Melbourne East General Practice Network, Melbourne General Practice Network, Northern Division of General Practice, Pivot West and Westgate General Practice Network; staff of all ACHs, EDs and ambulance services involved in the trial; and members of the reference group, for invaluable input to the project and commitment to improving the care of older people in residential care. Thanks to Dr Andrew Dent, former Director of the ED at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, for the birth of the checklist.

None identified.

- 1. Crilly J, Chaboyer W, Wallis M. Continuity of care for acutely unwell older adults from nursing homes. Scand J Caring Sci 2006; 20: 122-134.

- 2. Hickman L, Newton P, Halcomb EJ, et al. Best practice interventions to improve the management of older people in acute care settings: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2007; 60: 113-126.

- 3. Wong MC, Yee KC, Turner P. A structured evidence-based literature review regarding the effectiveness of improvement interventions in clinical handover. eHealth Services Research Group, University of Tasmania, for the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2008. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/PriorityProgram-05 (accessed Feb 2009).

- 4. Pothier D, Monteiro P, Mooktiar M, Shaw A. Pilot study to show the loss of important data in nursing handover. Br J Nurs 2005; 14: 1090-1093.

- 5. Australian Department of Health and Ageing. Aged Care General Practitioner Panels Initiative handbook. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/aged-care-gp-toc (accessed Mar 2009).

- 6. Belfrage M, Chiminello C, Cooper D, Douglas S. Final report: aged care home transfer-to-hospital envelope trial. Melbourne: North East Valley Division of General Practice, 2008. http://www.nevdgp.org.au/files/primarycaresupport/agedcareinitiative/Final%20Report%20% 20ACH%20Transfer-to-Hospital%20Envelope%20Trial%20October%202008.pdf (accessed Mar 2009).

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the use and usefulness of an aged-care home (ACH) transfer-to-hospital envelope (the Envelope) as a tool to support safe clinical handover when an ACH resident is transferred to an emergency department (ED).

Design, setting and participants: Participants in the study were 26 ACHs (1545 beds), the EDs of six major metropolitan public teaching hospitals in Melbourne, and ambulance officers involved in transferring residents from ACHs to hospitals. Transfer data were collected over an 18-week period (January–May 2008). Evaluation methods included written surveys and semi-structured face-to-face interviews (interviewees were 19 ACH staff, 30 ED staff, and 7 ambulance officers familiar with the Envelope).

Main outcome measures: Use, usefulness and ease of use of the Envelope; impact of using the Envelope on clinical handover; awareness of the need for clinical handover; sustainability of the project.

Results: The Envelope was used for the large majority of ACH residents transferred to hospital (ACH data: 317/355 [89%]; ED data: 85/101 [84%]); 163/165 ACH staff (99%) thought the Envelope was useful, and 148/165 (90%) said it was easy to use; 128/165 ACH staff (78%) and all interviewees believed that using the Envelope improved clinical handover; and 152/165 ACH staff (92%) indicated they would continue to use the Envelope. All interviewees thought that using the Envelope had raised awareness of the need for clinical handover.

Conclusion: The Envelope is useful and easy to use. It is used in the large majority of transfers of ACH residents to EDs and is highly valued by ACH staff, ambulance officers and ED staff. Our results suggest that use of the Envelope makes clinical handover safer for patients.