Clinical records

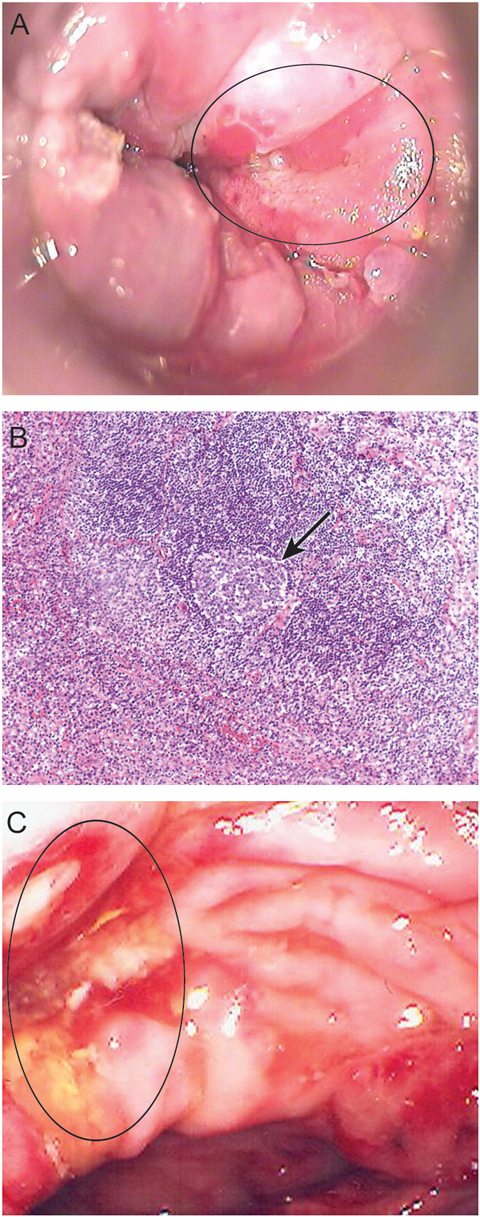

A 55-year-old man presented with tenesmus, rectal bleeding and discharge of 3 weeks’ duration. He had a past history of treated syphilis and anal warts. High-resolution anoscopy, performed by a sexual health physician, revealed an extensive anterior ulcer distal to the dentate line, suggestive of anal carcinoma (Figure A). However, histological examination of repeated rectal biopsies revealed non-specific ulceration, with chronic inflammation in the adjacent rectal glandular mucosa.

A 54-year-old man with previously treated syphilis presented with a 2-week history of per-rectal bleeding, pain and associated fevers. Colonoscopy, performed by a gastroenterologist, revealed extensive rectal ulceration. Histological examination of a biopsy from the ulcer revealed ulceration with mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cells and a lymphoid infiltrate, suggestive of a lymphoma (Figure B). A sigmoidoscopy was performed 7 days later, when the patient re-presented with worsening rectal pain and bleeding. Repeat rectal biopsies confirmed non-specific inflammation with atypical Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoid proliferation rather than lymphoma.

A 43-year-old man with previous Kaposi’s sarcoma presented with a 2-month history of per-rectal bleeding and diarrhoea. Colonoscopy, performed by a surgeon, showed multiple rectal ulcers suggestive of Crohn’s disease (Figure C), but biopsies showed non-specific acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrates only.

Chlamydia trachomatis is a human pathogen and a common cause of sexually transmitted infections, including lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV).1 LGV was previously confined to endemic areas in tropical regions — principally Africa, India and northern South America. However, since 2003, LGV has emerged as an increasingly important infection worldwide, with outbreaks occurring in communities of men who have sex with men (MSM) in The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom and North America.2-6 Risk factors identified in these outbreaks include HIV seropositivity, previously diagnosed sexually transmitted infections, concurrent ulcerative disease, and unprotected receptive anal sex with casual partners. In Australia, there have only been two previous reported cases of LGV. Both patients were MSM. One patient presented with inguinal lymphadenopathy acquired in Melbourne,7 while the other had anorectal LGV acquired after sexual exposure in Europe.8

Unlike other chlamydial infections, which are generally restricted to epithelial surfaces, LGV is invasive and causes severe inflammation, often with systemic symptoms and with a preference for lymphatic tissue.1 The manifestations of LGV infection vary depending on the site of inoculation, presenting either as a painful unilateral inguinal syndrome or an anorectal syndrome.

Lessons from practice

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an invasive inflammatory disease of the urogenital tract caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. LGV is an important cause of anorectal disease in men who have sex with men.

Anorectal LGV may masquerade as inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal malignancy, lymphoma or other ulcerative rectal sexually transmitted infections.

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. It is important to take a detailed sexual history and conduct specific microbiological testing for C. trachomatis.

Screening for coinfection, contact tracing, general education and health promotion are important public health components of managing LGV.

LGV infection is characterised by three stages. In the first stage, the primary lesion is usually an asymptomatic small genital ulcer that heals spontaneously. This is followed by a painful inguinal lymphadenopathy associated with systemic features. Lymph node inflammation may progress to involve the surrounding subcutaneous tissue, causing an inflammatory mass (bubo) and/or abscess. Complications occur in 30% of cases as a result of bubo rupture and/or sinus tract or fistula formation. In anorectal disease, acute haemorrhagic inflammation of the colon and rectum is associated with involvement of perirectal lymphatic tissue.1,9 The third stage is characterised by chronic granulomatous inflammation leading to lymphatic obstruction, fibrosis and stricture formation.1

Clinical proctitis is a common problem in MSM, and C. trachomatis is one of the most frequent infectious agents found in this population. When suspected, C. trachomatis infections can be quickly identified and treated. However (as was the case with the patients described here), infected people may present to non-sexual-health practitioners (eg, gastroenterologists or colorectal surgeons) for persisting symptoms.9 Endoscopic features are non-specific, with a wide range of differential diagnoses including Crohn’s disease, lymphoma, anorectal carcinoma and other sexually transmitted ulcerative infections (eg, syphilis, herpes).3,4,9 Biopsies typically show only non-specific inflammatory features.

C. trachomatis is divided into 15 serovars, labelled A, B, Ba, C–K and L1–L3, based on analysis of the major outer membrane protein. The various serovars are associated with specific disease manifestations: serovars A, B, Ba and C cause trachoma; serovars D–K are associated with urogenital infection; and serovars L1–L3 cause LGV.10 The L2 serovar can be further separated into L2, L2', L2a or L2b according to minor differences in their component amino acids.9

- 1. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect 2002; 78: 90-92.

- 2. Kropp RY, Wong T; Canadian LGV Working Group. Emergence of lymphogranuloma venereum in Canada. CMAJ 2005; 172: 1674-1676.

- 3. Ahdoot A, Kotler DP, Suh JS, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereum in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals in New York City. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40: 385-390.

- 4. Tinmouth J, Rachlis A, Wesson T, Hsieh E. Lymphogranuloma venereum in North America: case reports and an update for gastroenterologists. Clin Gasteroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 469-473.

- 5. Williams D, Churchill D. Ulcerative proctitis in men who have sex with men: an emerging outbreak. BMJ 2006; 332: 99-100.

- 6. Van der Bij AK, Spaargaren J, Morre SA, et al. Diagnostic and clinical implications of anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men: a retrospective case–control study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: 186-194.

- 7. Eisen DP. Locally acquired lymphogranuloma venereum in a bisexual man [letter]. Med J Aust 2005; 183: 218-219. <MJA full text>

- 8. Morton AN, Fairley CK, Zaia AM, Chen MY. Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in a Melbourne man. Sex Health 2006; 3: 189-190.

- 9. Nieuwenhuis RF, Ossewaarde JM, Götz HM, et al. Resurgence of lymphogranuloma venereum in Western Europe: an outbreak of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 proctitis in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 996-1003.

- 10. Geisler WM, Suchland RJ, Whittington WL, Stamm WE. The relationship of serovar to clinical manifestation of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30: 160-165.

None identified.