Rainfall of up to 275 mm in 24 hours and wind gusts exceeding 130 km/hour1,2 caused widespread flooding and damage to houses, businesses, schools, hospitals, nursing homes and community health centres. Local infrastructure was severely affected, with interruptions to power, water and gas supplies, sewerage system failures and rail line damage. Many roads were impassable because of flood water, fallen trees, fallen powerlines and abandoned cars. The Pasha Bulker, a bulk coal carrier with 780 tonnes of oil and fuel on board, was grounded on Nobby’s Beach, Newcastle, on 8 June.3

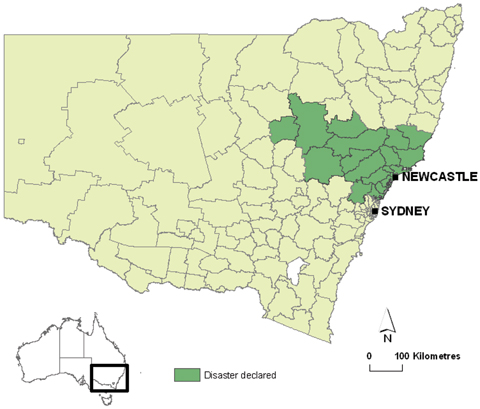

The NSW State Emergency Service responded to almost 20 000 storm-related calls, including requests for assistance with fallen trees, damaged houses and leaking roofs.4 Flood water resulted in thousands of evacuations, including about 6000 residents of Maitland and Lorn when the Hunter River threatened to breach its levee. A natural disaster was declared in 19 local government areas (Box 1).4 The region was affected by two more severe weather events in the following 2 weeks, which caused further flooding and property damage. The total damage bill is expected to reach $1.5 billion.5

Over 200 000 homes and businesses were affected by storm-related electricity interruptions, which caused failure of household winter heating and hot water, difficulty preparing hot food, and food spoilage.6 Some properties had no electricity for more than a week. The scale of the public health threat was immediately apparent: 207 private or commercial drinking water supplies, 1200 food premises, 2600 waste water disposal systems (septic tanks) and three public swimming pools were affected by flooding or power outage in the Hunter New England Area.

A public health emergency operations centre was established in the Area to coordinate surveillance activities, prevent disease outbreaks and respond to public health issues under emergency arrangements outlined in the NSW Healthplan.7 Internal communication and information technology in the operations centre played a critical role in the success of the public health response by ensuring that accurate, up-to-date information was provided to the public health controller for appropriate and timely decision making. The public health response is summarised in Box 2.

The loss of electricity in parts of the greater Newcastle and Lake Macquarie region affected water and sewerage services because electric pumps failed. Restoring a safe water supply to households was made the highest priority. Affected water reservoirs were filled by rerouting water reticulation until electricity was restored or temporary portable generators could be deployed. Two small water utilities in the Hunter Valley were also affected, and they introduced water restrictions to conserve safe stored water. One council utility had no option but to draw water from the Hunter River, resulting in high turbidity. It issued precautionary advice to consumers to boil water until treated water met Australian Drinking Water Guidelines requirements.8

These fact sheets were loaded onto the NSW Office for Emergency Services website (http://www.emergency.nsw.gov.au) and distributed to the media, support agencies and disaster recovery centres. Fact sheets covered the risks of contaminated flood water, food safety, cleaning and disinfecting of domestic food utensils and equipment, vegetable and herb garden contamination, and cleaning of domestic swimming pools and underground rainwater tanks. Public health experts also attended some community meetings at the request of affected communities.

Within a fortnight of the storm, Hunter New England Population Health conducted a survey of 215 randomly selected households from two of the worst affected local government areas: Newcastle and Lake Macquarie. This survey examined preparedness and access to information in order to learn from the disaster and improve the response to future disasters. The survey found that the local ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) radio station (1233 ABC Newcastle) had played an important role in providing public information during the storm. The survey also found that around half of households were unaware of storm warnings on 7 June. Deficiencies in disaster preparedness were also identified: some households lacked recommended basic equipment, such as battery operated radios, appropriate batteries, first-aid kits and emergency contact lists.9

Since the storm, NSW Health has made a formal proposal to the State Emergency Management Committee for the development of a memorandum of understanding between the NSW State Emergency Service organisations and the NSW ABC to facilitate communication with the public during disasters. Such arrangements already exist in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia.10

1 New South Wales local government areas that were declared natural disaster areas as a result of the storm in June 2007

2 Public health activities in the Hunter New England Area in response to the storm in June 2007

Instituting a surveillance system for storm-related health presentations to emergency departments, community pharmacies and general practices throughout the storm-affected area

Communicating with relevant emergency service agencies through daily situation reports

Providing public health advice through regular media releases and interviews with television, radio and print media

Developing and distributing fact sheets containing public health advice

Setting up and monitoring a health hotline

Liaising at least daily with affected water utilities to determine water quality and availability and the status of sewerage systems

Coordinating the local government public health response through daily teleconferences with seven local governments

Providing health risk assessments for evacuation centres, disaster recovery centres, storm-damaged schools, and the Pasha Bulker site.

- Michelle A Cretikos1

- Tony D Merritt2

- Kelly Main2

- Keith Eastwood2

- Linda Winn3

- Lucille Moran2

- David N Durrheim2,4

- 1 Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Hunter New England Population Health Unit, Hunter New England Area Health Service, Newcastle, NSW.

- 3 Hunter New England Area Health Service, Newcastle, NSW.

- 4 Hunter Medical Research Institute, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW.

None identified.

- 1. Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Newcastle, New South Wales: June daily weather observations. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/dwo/200706/html/IDCJDW2097.200706.shtml (accessed Oct 2007).

- 2. Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Newcastle University, New South Wales: June daily weather observations. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/dwo/200706/html/IDCJDW2098.200706.shtml (accessed Oct 2007).

- 3. New South Wales Maritime Authority. Update: Pasha Bulker incident [press release]. Sydney: NSW Maritime Authority, 2007; 9 Jun; 11:00. http://www.maritime.nsw.gov.au/mediareleases/media-shipgroundsIII.html (accessed Oct 2007).

- 4. Emergency Management Australia. Disasters database. NSW east coast storm and flood event. Canberra: EMA, 2007. http://www.ema.gov.au/ema/emadisasters.nsf/9d804be3fb07ff5cca256d1100189e22/99221b6 265ebad62ca2573070025a88c?OpenDocument (accessed Oct 2007).

- 5. John D. Winter storm bill expected to reach $1.5b. Sydney Morning Herald 2007; 25 Aug. http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/winter-storm-bill-expected-to-reach-15b/2007/08/24/1187462523612.html (accessed Oct 2007).

- 6. Energy Australia. Crews return home after powerful restoration effort [press release]. Sydney: Energy Australia, 2007; 15 Jun. http://www.energy.com.au/energy/ea.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/070614 +thank+you+release.pdf+/$FILE/070614+thank+you+release.pdf (accessed Oct 2007).

- 7. NSW Health. NSW Healthplan: a supporting plan to the New South Wales State Disaster Plan (Displan). NSW Health, 2005. http://www.emergency.nsw.gov.au/media/252.pdf (accessed Oct 2007).

- 8. National Health and Medical Research Council and Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council. Australian drinking water guidelines. Ref. EH19. Canberra: NHMRC, 2004. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/eh19syn.htm (accessed Oct 2007).

- 9. Emergency Management Australia. A checklist for your emergency survival kit. Canberra: EMA. http://www.ema.gov.au/agd/ema/rwpattach.nsf/VAP/(A80860EC13A61F5BA8C1121176F6CC3C)~PFTU_checklist2007.pdf (accessed Oct 2007).

- 10. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ABC Victoria and Victorian Emergency Services Organisations memorandum of understanding. Melbourne: ABC, 2004. http://www.oesc.vic.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/OESC/Home/Strategic+Partnerships/Formal+Agreements/OESC+-+ABC+Victoria+and+Victorian+Emergency+Services+Organisations+Memorandum+of+Understanding+%28PDF%29 (accessed Oct 2007).

Abstract

A severe storm that began on Thursday, 7 June 2007 brought heavy rains and gale-force winds to Newcastle, Gosford, Wyong, Sydney, and the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales.

The storm caused widespread flooding and damage to houses, businesses, schools and health care facilities, and damaged critical infrastructure.

Ten people died as a result of the storm, and approximately 6000 residents were evacuated.

A natural disaster was declared in 19 local government areas, with damage expected to reach $1.5 billion.

Additional demands were made on clinical health services, and interruption of the electricity supply to over 200 000 homes and businesses, interruption of water and gas supplies, and sewerage system pump failures presented substantial public health threats.

A public health emergency operations centre was established by the Hunter New England Area Health Service to coordinate surveillance activities, respond to acute public health issues and prevent disease outbreaks.

Public health activities focused on providing advice, cooperating with emergency service agencies, monitoring water quality and availability, preventing illness from sewage-contaminated flood water, assessing environmental health risks, coordinating the local government public health response, and surveillance for storm-related illness and disease outbreaks, including gastroenteritis.

The local ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) radio station played a key role in disseminating public health advice.

A household survey conducted within a fortnight of the storm established that household preparedness and storm warning systems could be improved.