Bedwetting without daytime symptoms, the most common toileting problem, can be effectively treated with an alarm device

Micturition is modulated by the higher centres of the brain and occurs in the aroused or awake state (even in newborns). There is electroencephalographic evidence of cortical arousal during sleep in response to bladder distension. Between 1 and 2 years of age, a conscious sensation of bladder filling develops. The ability to void or inhibit voiding voluntarily develops by 2–3 years, together with a social consciousness regarding urination. Many parents begin toilet training their child at this time (see Box 1 in the next article in this series, Constipation and toileting issues in children. MJA 2005; 182: Number 5). By the age of 3–4 years, most children have an adult pattern of urinary control and are dry both day and night.1

The bladder normally accommodates urine at a low and stable pressure as it fills during the storage phase. When the bladder reaches a certain size, a sensation of fullness is perceived and a desire to void is felt, with no feelings of discomfort or urgency and no urinary leakage. The normal voiding phase is characterised by voluntary initiation of micturition, with relaxation of the pelvic floor and external urethral sphincter, and contraction of the detrusor muscle surrounding the bladder (which may be voluntary or involuntary), resulting in a forceful and continuous urine flow with complete bladder emptying.

Bladder capacity increases during the first 8 years of life and normal bladder capacity for children 0–8 years is about (age + 1) × 30 mL.1 The normal frequency of voiding in children and adults is four to seven times per day, or every 2–3 hours.2 Usually, there is reduced urine production at night (of about 50% daytime levels) in response to the circadian rhythm of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH).2 Nocturnal polyuria occurs when overnight urine production exceeds this.

Uroflowmetry measures the rate of urine flow during voiding. The normal flow curve is smooth and bell-shaped. Abnormal flow curves suggest obstruction (eg, caused by pelvic-floor overactivity with involuntary intermittent contraction of the periurethral striated muscles during voiding), or reduced detrusor contractility, with reduced strength or duration of detrusor contraction resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or failure to completely empty the bladder.

The residual volume of urine after voiding can be measured by a postvoid ultrasound examination of the bladder. The normal residual urine volume in children should be less than 10% of maximal bladder capacity. Increased residual urine volume suggests incomplete bladder emptying, which is caused by the periurethral muscles contracting before the bladder completely empties (eg, in pelvic-floor overactivity).3 Uroflowmetry and residual urine volume measurements are not necessary for the routine management of bedwetting, but they are useful tools for assessing children with daytime symptoms, particularly those who do not respond to treatment.

The impact of bedwetting on children and families can be significant. It can affect a child’s self-esteem, interpersonal relationships with peers and parents (with increased risk of physical abuse), and have an impact on schooling (underachieving at school) and later sexual activity.4 Children are often teased by siblings and friends and are reluctant to participate in school trips requiring an overnight stay or to attend sleepovers.4 In Australia, only 34% of families of children with bedwetting seek professional help.5 The attitudes of the child and the parents to bedwetting (desire and motivation to change) influence the likelihood of treatment success.6

Bedwetting occurs in up to 20% of school-aged children, with 2.4% wetting at least nightly.5 The prevalence is about 20% in 5 year olds, 10% in 10 year olds and 3% in 15 year olds.7 Children tend to outgrow bedwetting, with a spontaneous remission rate of about 14% annually among bedwetters (with 3% remaining enuretic as adults).7 Bedwetting is more common in boys. A quarter of school-aged children with bedwetting have associated daytime symptoms (with or without wetting).1

Daytime urinary incontinence of mild severity (at least once in the past 6 months) occurs in up to 20% of school-aged children, with 2.0% wetting twice or more per week and 0.7% wetting every day.8 Daytime incontinence is more common in girls.1

The aetiology of bedwetting is multifactorial, with a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors. It is important to distinguish the different forms of enuresis (Box 1), as aetiology and management differ.

Primary nocturnal enuresis: Important risk factors include family history, nocturnal polyuria, impaired sleep arousal and nocturnal bladder dysfunction. Bedwetting has been linked to chromosomes 13, 12, 8 and 22, with a predominantly autosomal dominant inheritance.7 In two-thirds of children with bedwetting, a disturbed circadian rhythm of ADH release and nocturnal polyuria have been found.10 Defects in sleep arousal have also been associated with bedwetting.11 As many as a third of children with enuresis may have nocturnal detrusor overactivity, with reduced functional bladder capacity. These children have normal detrusor activity and a normal functional bladder capacity when they are awake, but a reduced functional bladder capacity with detrusor overactivity when they are asleep.12 Other risk factors for primary nocturnal enuresis include constipation,13 developmental delay and other neurological dysfunction,14 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),15 upper-airway obstruction16 and sleep apnoea.17 It has been postulated that nocturnal enuresis in people with airway obstruction results from increased production of atrial natriuretic peptide, which increases the arousal threshold in sleep.

Secondary nocturnal enuresis: Risk factors include urinary tract infections (which may cause temporary detrusor and/or urethral instability), diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus, stress, sexual abuse and other psychopathological conditions, as well as some of the risk factors for primary nocturnal enuresis, such as constipation and upper-airway obstruction.7

Daytime incontinence: Risk factors include a family history of daytime symptoms, urinary tract infections, neuropathic bladder (in spinal cord conditions such as spina bifida), urological disorders (in urinary tract anomalies such as urethral duplication and epispadias), and psychiatric disorders.7,8

The age at which parents seek treatment for their child’s wetting problems is often influenced by the severity of symptoms and by parental and child concern. Usually, it is around school age (5–6 years) for daytime incontinence and 7–8 years for bedwetting.

A thorough history and physical examination are most important in assessing a child with a wetting problem. The history of wetting will differentiate primary from secondary enuresis, and monosymptomatic from non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, and therefore direct management. When seeking help for bedwetting, many parents are not aware of their child’s daytime symptoms.

Children with nocturnal enuresis and any daytime wetting problems should be diagnosed as incontinent, as the nocturnal enuresis is part of the overall incontinence. The nature of the wetting (frequency, volume, waking after wetting), as well as associated symptoms (daytime symptoms, constipation or soiling, fluid intake and history of airway obstruction), should be assessed.

Daytime symptoms may reflect bladder dysfunction or dysfunctional voiding.

Bladder dysfunction may be caused by detrusor overactivity, with involuntary detrusor contraction during bladder filling resulting in symptoms of urgency (a sudden, compelling desire to void which is difficult to defer) and/or frequency (voiding more than seven times per day), with or without urge incontinence (involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by urgency), which is often associated with a small functional bladder capacity.

Dysfunctional voiding includes abnormal voiding frequency (with voiding more than seven or less than four times per day), staccato or interrupted voiding (urine flow is not continuous), increased postvoid residual volumes, and involuntary dribbling of urine after completion of voiding.

Other relevant history includes sleep history (adequacy of sleep, symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea, and whether the child wakes during the night to void or is aware of the bedwetting), developmental history, past medical history (such as urinary tract infection), family history, and medications (which may have possible effects on the lower urinary tract). Examination should include urinalysis (to identify infection and glycosuria), and examination of the spine, abdomen and genitalia.

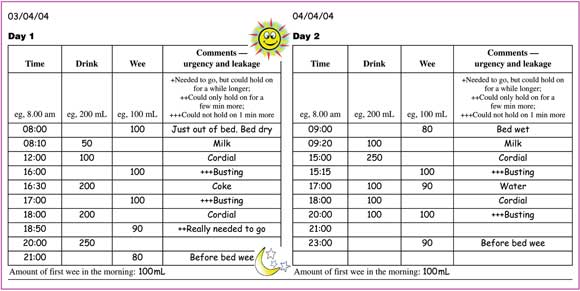

Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: Unless there is suspicion of other disease states, a urine culture to exclude urinary tract infection is the only investigation indicated.2 A frequency/volume chart (with documentation of the time and volume of all fluid intake and urine output in 24-hour periods (see Case Study) can give objective information about frequency of urination and functional bladder capacity. Overnight urine production (to assess nocturnal polyuria) is measured by adding the volume of the first morning void with the overnight volume, calculated by the before-and-after weight of a nappy worn overnight by the child.

Incontinence (day and night wetting): For these children, routine investigations include ultrasound imaging of the upper and lower urinary tract to assess for abnormalities, such as dilatation of the collecting system and gross reflux nephropathy, or bladder-wall thickening (which may indicate long-standing detrusor overactivity). Other possible investigations include abdominal x-ray to assess for constipation (when it is not clear whether this is a problem), urinary flow recording, postvoid residual volume assessment by ultrasound imaging, and spinal x-ray to detect spinal cord disease (which may cause a neuropathic bladder).

The initial treatment of choice for children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is an enuresis alarm. There are two types of alarms available in Australia:

A pad-and-bell alarm — the child lies on a large pad placed in the bed and any liquid triggers the alarm; and

A personal alarm — the alarm is clipped onto the child’s underpants or onto a continence pad placed inside the child’s underpants and any liquid triggers the alarm.

Both types have been shown to be equally effective,18 although the personal alarm is more likely to be disconnected during the night. The choice is based on availability and patient acceptance. Children generally use the alarm until they achieve 14 consecutive dry nights, with treatment beyond 16 weeks being unlikely to produce a cure.19 Two-thirds of children become dry during alarm use, and about half remain dry after using alarms compared with almost none after no treatment.18 Relapse can be avoided in an additional 25% of children by using overlearning — giving extra bedtime fluids while continuing to use the alarm after successfully achieving night dryness.18

The ADH analogue desmopressin is effective in 60% of children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. These children are more likely to be those with a disturbed circadian rhythm of ADH release and nocturnal polyuria. Compared with desmopressin, alarms are about 30% more effective for treating bedwetting and about 70% more effective in preventing relapse after treatment has ceased.18 Desmopressin has a more immediate effect, but limited sustained effect.18 Desmopressin can be used in the short term to reduce the frequency of wetting for a specific purpose, such as nights away from home. Desmopressin is now available in tablet form as well as a nasal spray. Hyponatraemia is the most serious potential complication of desmopressin therapy (associated with overdrinking at bedtime). Treatment for nocturnal enuresis is summarised in Box 3.

For non-responders to individual alarms or desmopressin therapy, combination therapy with an alarm and desmopressin can be tried,1 although there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate effectiveness.18 Anticholinergics (oxybutynin) can be used in children with nocturnal detrusor overactivity, identified clinically as the group who do not respond to either desmopressin therapy or alarms.18 Although tricyclic antidepressants and related drugs are effective in about 20% of cases, they are no longer recommended for the treatment of bedwetting because of their potentially serious cardiotoxic adverse effects.20

Evidence-based practice tips

Enuresis alarm is the treatment of choice in children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (I).18

Desmopressin is also effective for nocturnal enuresis, but less effective than alarms, and the benefit is not sustained (I).21

An enuresis alarm and desmopressin in combination may be effective in children resistant to treatment with alarm alone or desmopressin alone (II).1

Children with daytime symptoms are more resistant to treatment and more vulnerable to relapse. Treatment includes a combination of bladder training with regular voiding regimens, anticholinergics and normalising fluids (III-2).1

Levels of evidence (I–IV) are derived from the National Health and Medical Research Council’s system for assessing evidence.26

There is insufficient evidence to demonstrate the efficacy of other commonly used interventions for monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, such as simple behavioural and physical interventions (fluid restriction before bedtime, lifting, scheduled waking, star charts and other reward systems, retention control training), although these are widely used as first-line therapy.21 Comparing complex behavioural and educational interventions, such as dry-bed training (intensive training with regular waking at night), or full-spectrum home training (combined enuresis alarm with cleanliness training, retention control and overlearning), with an enuresis alarm alone, showed the alarm method to be better than the complex method without an alarm, but dry-bed training supplemented by an enuresis alarm may reduce the relapse rate.22 In children with upper-airway obstruction, treatment of the obstruction may stop bedwetting.16

Children with daytime symptoms are more resistant to treatment and more vulnerable to relapse than children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis.23 Motivation of the child and family is necessary for success, and frequent follow-up is required.

Treatment should first be aimed at daytime symptoms. Although daytime symptoms are most commonly caused by detrusor instability or dysfunctional voiding, it is important to exclude other causes, such as neurological or urological causes. Treatment includes a combination of urotherapy (teaching children to relax their pelvic-floor muscles during voiding), regular voiding regimens, anticholinergic therapy, and normalising fluid intake.1

Constipation and faecal impaction (with or without soiling) can cause detrusor overactivity, reduced functional bladder capacity and urinary tract infection. Treatment of constipation alone can cure enuresis.24 It is thought that reduced fluid intake and intake of caffeinated drinks, such as cola or chocolate drinks, may also exacerbate detrusor overactivity.25

Referral for specialist advice is highly recommended for treatment failure after 8–12 weeks for any form of bedwetting or daytime incontinence. Useful websites for noctural enuresis are listed in Box 4.

1 Bladder control terminology1,9

Nocturnal enuresis: Involuntary passage of urine at night, in the absence of physical disease, beyond the age of 5 years.

Primary nocturnal enuresis: The child has never been dry at night for more than 6 months. This is more common than secondary enuresis.

Secondary nocturnal enuresis: Bedwetting after a period of at least 6 months of night dryness. This is more likely to be associated with a recognisable psychological or organic cause.

Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: Bedwetting without daytime symptoms. This is the most common form of enuresis.

Non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: Bedwetting with daytime voiding symptoms, such as urgency and frequency, with or without daytime incontinence. This suggests underlying bladder dysfunction.*

Urinary incontinence: Daytime wetting with or without bedwetting.

* The International Children’s Continence Society (but not all groups) defines non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis as bedwetting with daytime voiding symptoms but without daytime incontinence, and defines bedwetting and daytime incontinence as urinary incontinence. However, as management is the same, we have grouped them together in this article.9

3 Treatment for nocturnal enuresis

Alarm therapy

Pad-and-bell alarm or personal alarm

To be used for a minimum of 14 consecutive dry nights to a maximum of 4 months

Desmopressin

Nasal spray 10–40 μg at night (start with 10 μg nightly and titrate up to 40 μg)

Tablet 200–400 μg at night

Available on authority prescription for children over 6 years who have failed alarm treatment or where alarm therapy is contraindicated.

4 Useful websites for nocturnal enuresis

The International Continence Society: www.continet.org/

The Continence Foundation of Australia: www.continence.org.au

The International Children’s Continence Society: www.i-c-c-s.org/

The National Continence Management Strategy (includes downloadable fact sheets in several languages): www.continence.health.gov.au/

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (series on nocturnal enuresis): www.thecochranelibrary.com

Bedwetting alarm

The battery-operated alarm is pinned onto the pyjama top and the sensor is placed between two pairs of underpants with a connecting lead. When the sensor detects any urine the alarm emits a siren sound and vibrates. Alternatively, the alarm can be set with a recording of the parent’s voice. (Photo courtesy of the Bedwetting Institute of Australia Pty Ltd <www.bedwettingcured.com.au>).

- Patrina H Y Caldwell1

- Elisabeth Hodson2

- Jonathan C Craig3

- Denise Edgar4

- 1 NHMRC Centre for Clinical Research Excellence in Renal Medicine, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 The Continence Foundation of Australia in New South Wales, Sydney, NSW.

- 1. Nijman RJM, Butler R, Van Gool J, et al. Conservative management of urinary incontinence in childhood. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Paris: Health Publication, 2002: 513-551.

- 2. Hjalmas K, Arnold T, Bower WF, et al. Nocturnal enuresis: an international evidence based management strategy. J Urol 2004; 171 (6 Pt 2): 2545-2561.

- 3. Homma Y, Batista J, Bauer S, et al. Urodynamics. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Paris: Health Publication, 2004: 317-372.

- 4. Redsell SA, Collier J. Bedwetting, behaviour and self esteem: a review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev 2001; 27: 149-162.

- 5. Bower WF, Moore KH, Shepherd RB, Adams RD. The epidemiology of childhood enuresis in Australia. Br J Urol 1996; 78: 602-606.

- 6. Morison MJ. Parents’ and young people’s attitudes towards bedwetting and their influence on behaviour, including readiness to engage in and persist with treatment. Br J Urol 1998; 81 Suppl 3: 56-66.

- 7. Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of urinary incontinence (UI). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Paris: Health Publication, 2002: 165-201.

- 8. Sureshkumar P, Craig JC, Roy LP, Knight JF. Daytime urinary incontinence in primary school children: a population-based survey. J Pediatr 2000; 137: 814-818.

- 9. Norgaard JP, Van Gool JD, Hjalmas K, et al. Standardization and definitions in lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. International Children’s Continence Society. Br J Urol 1998; 81 Suppl 3: 1-16.

- 10. Rittig S, Knudsen UB, Norgaard JP, et al. Abnormal diurnal rhythm of plasma vasopressin and urinary output in patients with enuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1989; 256: 664-671.

- 11. Kawauchi A, Imada N, Tanaka Y, et al. Changes in the structure of sleep spindles and delta waves on electroencephalography in patients with nocturnal enuresis. Br J Urol 1998; 81 Suppl 3: 72-75.

- 12. Yeung CK, Sit FK, To LK, et al. Reduction in nocturnal functional bladder capacity is a common factor in the pathogenesis of refractory nocturnal enuresis. BJU Int 2002; 90: 302-307.

- 13. O’Regan S, Yazbeck S, Hamberger B, Schick E. Constipation a commonly unrecognized cause of enuresis. Am J Dis Child 1986; 140: 260-261.

- 14. Jarvelin MR. Developmental history and neurological findings in enuretic children. Dev Med Child Neurol 1989; 31: 728-736.

- 15. Duel BP, Steinberg-Epstein R, Hill M, Lerner M. A survey of voiding dysfunction in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. J Urol 2003; 170 (4 Pt 2): 1521-1524.

- 16. Weider DJ, Hauri PJ. Nocturnal enuresis in children with upper airway obstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1985; 9: 173-182.

- 17. Brooks LJ, Topol HI. Enuresis in children with sleep apnea. J Pediatr 2003; 142: 515-518.

- 18. Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE. Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2003. Oxford: Update Software.

- 19. Forsythe WI, Redmond A. Enuresis and the electric alarm: study of 200 cases. BMJ 1970; 1: 211-213.

- 20. Moulden A. Management of bedwetting. Aust Fam Physician 2002; 31: 161-163.

- 21. Glazener CMA, Evans JHC. Simple behavioural and physical interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library Issue 1. 2004. Oxford: Update Software.

- 22. Glazener CMA, Evans JHC, Peto RE. Complex behavioural and educational interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library Issue 1. 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- 23. Fielding D. The response of day and night wetting children and children who wet only at night to retention control training and the enuresis alarm. Behav Res Ther 1980; 18: 305-317.

- 24. Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic constipation of childhood. Pediatrics 1997; 100: 228-232.

- 25. Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol 1990; 66: 613-614.

- 26. National Health and Medical Research Council. How to use the evidence: assessment and application of scientific evidence. Handbook series on preparing clinical practice guidelines. Table 1.3: Designation of levels of evidence. Canberra: NHMRC, February 2000: 8. Available at: www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/pdf/cp69.pdf (accessed Sep 2004).

Abstract

Bedwetting (nocturnal enuresis) is common. It occurs in up to 20% of 5 year olds and 10% of 10 year olds, with a spontaneous remission rate of 14% per year. Weekly daytime wetting occurs in 5% of children, most of whom (80%) also wet the bed.

Bedwetting can have a considerable impact on children and families, affecting a child’s self-esteem and interpersonal relationships, and his or her performance at school.

Primary nocturnal enuresis (never consistently dry at night) should be distinguished from secondary nocturnal enuresis (previously dry for at least 6 months). Important risk factors for primary nocturnal enuresis include family history, nocturnal polyuria, impaired sleep arousal and bladder dysfunction. Secondary nocturnal enuresis is more likely to be caused by factors such as urinary tract infections, diabetes mellitus and emotional stress.

The treatment for monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting with no daytime symptoms) is an alarm device, with desmopressin as second-line therapy.

Treatment for non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting with daytime symptoms — urgency and frequency, with or without incontinence) should initially focus on the daytime symptoms.