The first English language report mentioning problem crying in infants — in The boke of chyldren, published in the 16th century — described it as related to “noyse and romblying in the guttes”.1 Although it has long been recognised that some infants cry more than others, the cause (or causes) remains elusive. Infants who present with persistent crying are probably a heterogeneous group, requiring a variety of management approaches. Although considered a trivial problem by many healthcare professionals, persistent crying in babies has been associated with maternal depression, family stress, family breakdown, and child abuse.2-4

From an evolutionary perspective, crying is an attachment behaviour, promoting proximity to the infant’s primary caregiver and ensuring survival and the development of social bonds.5 It is not surprising then that all infants cry. However, depending on the definition used, up to 20% of infants in the community cry excessively and are irritable.6 Traditionally, the criteria of Wessel et al have been used to define “problem crying”7 as unexplained crying and fussing lasting for more than 3 hours per day, on more than 3 days per week, for more than 3 weeks. However, many babies cry less than this but are still perceived by their parents to have a problem.

Crying begins in the first few weeks of life, and typically the duration peaks at 2.4 hours per day at the age of 6 weeks.8 Episodes of crying tend to cluster in the evening, but can occur throughout the day.9 Many parents report that, while crying, their infants go red in the face, pull up their legs, or pass wind. Such behaviour is most likely part of normal infant crying and not related to gastro-oesophageal reflux.10 For most babies, crying and irritability decrease substantially by the age of 3–4 months.9,11

Although the frequency of crying bouts and the timing of the crying “peak” are similar across cultures, the duration of crying bouts has been shown to be shorter when parenting practices include more carrying of babies and breastfeeding on demand.12,13

Crying in infants is related to the dynamics of the mother–infant relationship, including maternal anxiety and depression. A prospective study of 1204 infants examining psychosocial factors associated with persistent crying at 3 months found the risk factors to be life stress, poor partner support, unsatisfactory sexual relationships, more maternal physical health problems in pregnancy, a traumatic birth, and perceiving the hospital staff as hostile.14

For most infants, problem crying is part of a normal spectrum whereby babies who have not yet learned to “self-soothe” and regulate their own crying become persistent criers.15 This may be a response to tiredness or hunger. Tiredness should be suspected when an infant’s total sleep duration per 24 hours falls more than an hour short of the “average” for their age (see Box 3 – Sleep requirements). Hunger is more likely when a mother reports frequent feeds (ie, < 3 hourly), poor weight gain and inadequate milk supply.

Less than 5% of babies with problem crying have an identifiable organic cause,15,16 as outlined in the diagnostic and management flowchart for infant irritability (Box 1).

No causal relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) and infant crying and irritability has been demonstrated.7 In a study of 70 infants with persistent crying, abnormally frequent or prolonged GOR (assessed by pH monitoring) only occurred in babies who vomited more than five times a day.17 “Silent reflux” — reflux without vomiting — did not occur. The duration of daily crying did not correlate with the severity of GOR.

Many health professionals continue to treat babies with antacid medications, but there are no blinded, randomised controlled trials of their effectiveness in irritable infants.18 Both ranitidine10 and omeprazole are ineffective in reducing crying.19,20 Thus, in the absence of frequent vomiting, antireflux medication to manage persistent infant irritability is not recommended.

In some irritable infants, food allergy may play a causal role, but its contribution to infant irritability in the general community is unknown. Food allergens commonly implicated include cow’s milk protein and soy protein,21 both of which can be found in human breast milk. These allergens can cause immediate reactions (vomiting, erythema where formula or breast milk touches the skin and/or urticaria developing within 2 hours of ingestion) or delayed reactions (vomiting and diarrhoea 2–48 hours after ingestion).22

Infants with food allergies usually present with one or more of the following symptoms: vomiting, blood or mucus in diarrhoea, poor weight gain, and signs of atopic disease (eg, eczema or wheezing). However, the presence of any one of these symptoms is not diagnostic of food allergy. In practice, a trial of eliminating cow’s milk by modifying the mother’s diet or changing the formula may be the best diagnostic test. For breastfed infants, a mother must remove all cow’s milk and cow’s milk products from her diet (including casein and whey products). Breastfeeding mothers can use soy milk and should consider taking a calcium supplement. Formula-fed babies may improve with a soy-based formula. However, some infants are allergic to both cow’s milk and soy protein. For these babies, changing to extensively hydrolysed formulas (eg, Pepti Junior, Nutrica, Australia) can be effective.23 An estimated 10%–15% of babies with cow’s milk allergy are also intolerant of extensively hydrolysed formulas and, for these babies only, treatment with amino acid formulas (eg, Neocate, Scientific Hospital Supplies, Australia) is indicated.23 These products should be trialled for at least 2 weeks to gauge response.

The role of lactose intolerance as a cause of infant irritability remains debatable. It has been hypothesised that some babies have a transient underlying lactase deficiency, leading to a build-up of lactose derived from breast milk or formula. Gut bacteria break down the lactose, converting it to lactic acid and hydrogen.24 The resulting acidic faeces may cause perianal excoriation. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of 46 infants with excessive crying and diarrhoea, treating breast milk or formula with lactase drops resulted in significantly less crying.23 These results may not apply to infants without these symptoms. Diagnosis of lactose intolerance includes testing for faecal-reducing substances (Box 1). A clinical response to a lactose-free diet confirms the diagnosis. Lactose-free formula is readily available. For breastfed babies, expressed breast milk needs to be pretreated with lactase drops for 12–24 hours and then given to the baby in a bottle. Alternatively, lactase tablets (Lacteeze, Allergy Free, Australia) can be crushed and a small amount placed inside the baby’s mouth before breastfeeding (as per the manufacturer’s instructions).

Anticholinergic medications (eg, dicyclomine [Merbentyl, Sigma]) have been shown in three randomised controlled trials to effectively reduce infant crying.18,20 However, the risk of adverse events, including apnoea and seizures, precludes the use of these medications.25 Simethicone (Infacol Wind Drops, Pfizer; and Degas Infant Drops, Wyeth) has no effect on infant crying when compared with placebo.18,20

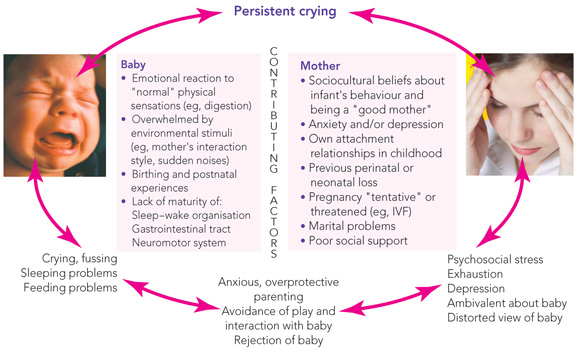

Infant behaviour needs to be understood in the context of the emotional development of the infant and the developing infant–parent relationship. Social and cultural beliefs, the “psychological style” of the parents (eg, degree of emotional responsivity, ability to deal with an infant’s total dependence), as well as the parents’ own childhood experiences, all influence how parents react and respond to persistent infant crying. The demands of fertility treatments may result in a tentative pregnancy and parents do not dare become too attached to the fetus. They may then be overwhelmed and unprepared for the reality of caring for a baby. Grief from previous neonatal loss may resurface with the birth of an infant, and it may be hard for parents to be convinced that this baby will be healthy and survive. Finally, postnatal anxiety or depression may impair a mother’s capacity to read her infant’s emotional states and behavioural cues. This may lead to soothing strategies not in tune with the infant’s state, a paucity of appropriate interaction and play opportunities, and a blunted emotional response to the infant.

Depressive symptoms are commonly reported by mothers of irritable or unsettled infants attending parenting centres.3,16 The extent to which this relationship holds in the general community is unknown. Infant irritability in the presence of other stressors, such as marital and transgenerational conflicts, insufficient social support or single parenthood, may also precipitate maternal depression (Box 2).26

For some infants, a lack of maturity in their ability to modulate their reactions to internal physical symptoms (eg, bowel spasm) and external stimuli (eg, loud noise) may result in problem crying. Clinical experience suggests that a traumatic birth may lead to infant distress, or, alternatively, infant sleepiness and difficulty in establishing a feeding routine. The mother may be emotionally and physically unavailable to help her baby with the early stages of learning to self-soothe and anticipate comfort.

Irritable babies have often been described as having a “difficult” temperament. However, temperament only plays a small part in infant irritability,4 and labelling an infant as difficult can lead to parents feeling helpless and powerless to change the underlying nature of the problem.28

As irritability in most infants has no underlying medical cause, the task of healthcare practitioners, after eliminating medical causes, is to explain babies’ normal crying and sleep patterns, to assist parents to help their baby deal with discomfort and distress, and to assess the mother’s emotional state and the mother–baby relationship.

Parents can use a simple diary to record their baby’s crying, feeding, and sleeping patterns on a daily basis (Box 4). A diary can show the baby’s usual crying patterns, the total amount of sleep the baby is having per 24 hours, and can help parents and doctors monitor the response to settling techniques. Most parents enjoy completing a diary. In some cases a diary can help them solve the problem by, for example, recognising that their baby sleeps better if he or she is awake for longer periods between daytime sleeps.

A number of different settling techniques are presented in books and videos, and recommended by parenting centres. They all aim to teach babies to fall asleep on their own and to ensure parents have a consistent approach to settling. Consistency is important in a “baby-centred” approach whereby the needs of the baby are addressed (eg, irritable babies require a consistent “message” about how to fall asleep) as well as the needs of the parent. Most techniques recommend that the parent pats or rocks the baby until he or she is quiet but not asleep. The parent then leaves the room. If the baby starts crying, the parent returns after a moment and, if the baby has not stopped crying, begins to resettle the baby. The process continues until the baby falls asleep. Such an approach has been shown to be effective in an uncontrolled trial of sleep-deprived infants staying in a parenting centre.31 It is unknown whether this is due to the approach, the opportunity for mothers to rest, or the other support and counselling offered at the centre.

All families with a crying infant are tired. Practical support is greatly needed to help families through this time. Parents should be encouraged to

mobilise help from family and friends;

rest once a day when the baby is asleep;

plan ahead for the baby’s most difficult time of the day (eg, by preparing dinner in advance); and

shop online, arrange home delivery of food, and, if financially feasible, arrange home help or a nanny.

When the situation becomes overwhelming, parenting centres which offer day or overnight stays can be invaluable (Box 5).

For most babies, problem crying and irritability settle by 3–4 months of age. Irritable babies are more likely to develop behaviour problems and sleep problems in the toddler and preschool years than babies who were not irritable, and families of irritable babies are less likely to have subsequent siblings than families of non-irritable babies.32

Evidence-based practice tips

Simethicone (Infacol Wind Drops and Degas Infant Drops) does not reduce infant irritability (I).18,20

In the absence of frequent vomiting, gastro-oesophageal reflux is an unlikely cause of infant irritability (III-2).17

For a subgroup of infants, a cow’s-milk-free diet may be beneficial (I).18

Levels of evidence (I–IV) are derived from the National Health and Medical Research Council’s system for assessing evidence.30

3 Primary care interventions

Eliminate medical causes of irritability History: Take a thorough history of the infant’s crying, sleeping and feeding patterns, the strategies tried, and the parents’ concerns. Ask about the pregnancy, birth experience, the mother’s pre-existing physical and mental health and current social supports, paying particular attention to the risk factors listed in Box 2. Ask about frequent vomiting (distinguish between vomiting and “possetting” small amounts of food, which is normal), diarrhoea, nappy rash, and atopic disease such as eczema. Ask about parents’ worst fears in regard to their infant, and, if appropriate, explain why you are sure that the baby’s distress is not related to these. It is hard for a baby to be reassured and soothed by parents who are frantically worrying that the baby is in pain or unwell. Examination: Perform a thorough examination, explaining what you are looking for. Look for eczematous rashes and perianal excoriation. Reassure parents that their baby is normal and healthy. Medications: Stop any inappropriate medications. Explain normal crying and sleep patterns Crying: Explain that all babies cry, that crying duration peaks at 6 weeks and that most crying disappears by 3–4 months of age. Sleep requirements: Explain normal sleep requirements for babies, emphasising that all babies are different and will therefore need different amounts of sleep. On average, babies sleep for 16 of every 24 hours at birth, falling to 14 hours by 2–3 months of age. If babies are awake during the day and happy, they are unlikely to need more sleep. Generally, a 6-week-old baby becomes tired after being awake for 1.5 hours, while a 3-month-old baby becomes tired after being awake for 2 hours. Recognising tiredness: Encourage parents to recognise when their baby is tired and put the baby to sleep then. Signs of tiredness can include frowning, clenched hands, jerking arms and legs, and crying or grizzling. Interaction and play: Discuss the baby’s need for interaction and play. For some families, a “campaign” to soothe the baby and avert a crying episode takes over. Some parents spend the whole day trying not to “overstimulate” their baby. Encourage parents to “go with the flow” — for example, by letting the baby continue to play if there are no signs of tiredness, or by taking the baby for a walk if he or she does not settle to sleep after 20–30 minutes. Alternatively, mothers can give their baby a warm, deep bath, and then try to settle the baby when he or she next looks tired. Assist parents to help their baby deal with discomfort and distress Normal physical sensations: Explain to parents that some babies may struggle to cope with normal physical sensations, such as digestion, elimination, normal reflux, tiredness and hunger. When babies find these sensations too overwhelming or frightening, they become irritable and cry. Reading an infant’s behaviour: Help parents to “read” their infant’s behaviour as an indicator of the infant’s emotional state and ways of self-regulating distress. Baby-centred approach: Discuss ways of helping this baby cope with distress. In your consulting room, observe the baby’s capacity to self-soothe when distressed. A baby who is easily startled and cannot calm him/herself down may need a quiet and gentle approach to nappy changing and bathtime and other day-to-day tasks. A baby who frantically looks around the room when distressed may need to be held in such a way that he or she can “lock onto” the mother’s face. The baby may then be able to be gently engaged in looking at something else in the room. Establish a predictable routine: Experiencing the world as less chaotic and frightening through a predictable routine of feeding and settling is important. The following may be appropriate:

Partnership with parents: Engage in a partnership with the parents to help the baby and the parents through this phase. Arrange proactive follow-up by phone or weekly review appointments. Reassurance that no medical problem exists may not be enough. Give mothers permission to rest once a day when their baby is asleep and not to carry out household chores. Assess maternal emotional state and mother–baby relationship

|

|||||||||||||||

5 Parenting support centres*

Victoria

Tweddle Child and Family Services (03 9689 1577)

O'Connell Family Centre (03 9882 2326)

Queen Elizabeth Centre (03 9549 2777)

New South Wales

Tresillian Family Care Centres (02 9787 0855 [Sydney] 1800 637 357 [outside Sydney])

Karitane Residential Unit (02 9794 1800)

Australian Capital Territory

Queen Elizabeth II Family Centre (02 6207 9977)

Queensland

Riverton Early Parenting Centre (07 3860 7111)

South Australia

Torrens House (08) 8303 1530

The Parenting Centre (08 8303 1566)

Western Australia

Ngala Family Resource Centre (08 9368 9368) (www.ngala.com.au/)

Tasmania

Parenting Centre, Hobart (03 6233 2700)

Walker House Parenting Centre, Launceston (03 6326 6188)

Parenting Centre, Burnie (03 6434 6201)

*More parenting support information is available at: www.kidscount.com.au/links/phone.asp

Case study — a 2-month-old boy with crying and irritability

A 2-month-old boy is brought to you by his mother because of difficulty settling to sleep, and excessive crying and irritability from Week 3. He currently tends to cry from 4 pm to 9 pm, but can cry any time of the day. When he cries, he arches his back, goes red in the face and his mother is unable to console him. She thinks he has “wind”. During the day he has two sleeps in the pram lasting 20 minutes each. At night, he is put to bed around 10 pm, sometimes wrapped, and falls asleep by himself. He wakes twice a night to breast-feed. He starts the day at 7 am. He is gaining weight and developing normally. He vomits once or twice a day. His mother has tried ranitidine 0.6 mL orally twice a day with little change. In your office, the baby suddenly starts to cry loudly. The mother rocks the pram but the baby cries more. So she picks him up, puts him over her shoulder and starts patting his back harder and harder while telling you about all the advice she has been given. Although the baby is crying, he is scanning the room with his eyes open. Management

Wrapping a baby for sleeps until around 6 months of age is recommended. |

|||||||||||||||

- 1. Phaer Thomas. The boke of chyldren (1544) (edited with an introduction, notes and glossary by Rick Bowers. Tempe, Ariz: Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1999. (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, vol 201.)

- 2. Pinyerd B. Strategies for consoling the infant with colic: fact or fiction. J Pediatr Nurs 1992; 7: 403-411.

- 3. McMahon C, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, et al. Postnatal depression, anxiety and unsettled infant behaviour. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35: 581-588.

- 4. Barr RG, Kramer M, PLess IB, et al. Feeding and temperament as determinants of early infant crying/fussing behavior. Pediatrics 1989; 84: 514-521.

- 5. Bowlby J. The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal 1958; 39: 350-373.

- 6. Wade S, Kilgour T. Infantile colic. BMJ 2001; 323: 440.

- 7. Wessel MA, Cobb JC, Jackson EB, et al. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called “colic”. Pediatrics 1954; 14: 421-424.

- 8. Brazelton TB. Crying in infancy. Pediatrics 1962; 29: 579-588.

- 9. St James-Roberts I, Halil T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: normal community and clinical findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1991; 32: 951-968.

- 10. Jordan B, Heine RG, Meehan M, et al. The irritable infant intervention study: effect of antireflux medication and infant mental health intervention on persistent irritability. Abstracts of the Division of Paediatrics Annual Scientific Meeting, May 1999 Perth. J Paediatr Child Health 1999; 35: A7.

- 11. Barr RG. Crying in the first year of life: good news in the midst of distress. Child Care Health Dev 1998; 24: 425-439.

- 12. St James-Roberts I, Bowyer J, Varghese S, Sawdon J. Infant crying patterns in Manali and London. Child Care Health Dev 1994; 20: 323-337.

- 13. Alvarez M. Caregiving and early infant crying in a Danish community. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2004; 25: 91-98.

- 14. Barr RG. Colic and crying syndromes in infants. Pediatrics 1998; 102: 1282-1286.

- 15. Armstrong K, Previtera N, McCallum RN. Medicalizing normality? Management of irritability in infants. J Paediatr Child Health 2000; 36: 301-305.

- 16. Rautava P, Helenius H, Lehtonen L. Psychosocial predisposing factors for infantile colic. BMJ 1993; 307: 600-604.

- 17. Heine R, Jaquiery A, Lubitz L, et al. Role of gastro-oesophageal reflux in infant irritability. Arch Dis Child 1995; 73: 121-125.

- 18. Garrison M, Christakis A. A systematic review of treatments for infantile colic. Pediatrics 2000; 106: 184-190.

- 19. Moore DJ, Tao BS, Lines DR, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr 2003; 143: 219-223.

- 20. Lucassen PL, Assendelft WJ, Gubbels JW, et al. Effectiveness of treatment for infantile colic: a systematic review. BMJ 1998; 316: 1563-1569.

- 21. Kilshaw PJ, Cant AJ. The passage of maternal dietary proteins into human breast milk. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1984; 75: 8-15.

- 22. Hill DJ, Firer MA, Shelton MJ, Hosking CS. Manifestations of milk allergy in infancy: clinical and immunological findings. J Pediatr 1986; 109: 270-276.

- 23. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000; 106: 346-349.

- 24. Kanabar D, Randhawa M, Clayton P. Improvement of symptoms of lactose intolerance following reduction in lactose load with lactase. J Hum Nutr Diet 2001; 14: 359-363.

- 25. Willimas J, Watkins-Jones R. Dicyclomine: worrying symptoms associated with its use in some small babies. BMJ 1984; 288: 901.

- 26. Murray L, Stanley C, Hooper R, et al. The role of infant factors in postnatal depression and mother infant interaction. Dev Med Child Neurol 1996; 38: 109-119.

- 27. von Hofacker N, Papousek M. Disorders of excessive crying, feeding, and sleeping: the Munich interdisciplinary research and intervention program. Infant Mental Health J 1998; 19: 180-201.

- 28. Barr RG. Changing our understanding of infant colic. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156: 1172-1175.

- 29. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of a 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 782-786.

- 30. National Health and Medical Research Council. How to use the evidence: assessment and application of scientific evidence. Handbook series on preparing clinical practice guidelines. Table 1.3: Designation of levels of evidence. Canberra: NHMRC, February 2000: 8. Available at: www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/pdf/cp69.pdf (accessed Sep 2004).

- 31. Don N, McMahon C, Rossiter C. Effectiveness of an individualized multidisciplinary programme for managing unsettled infants. J Paediatr Child Health 2002; 38: 563-567.

- 32. Rautava P, Lehtonen L, Helenius H, Sillanpaa M. Infantile colic: child and family three years later. Pediatrics 1995; 96: 43-47.

Abstract

Up to 20% of parents report a problem with infant crying or irritability in the first 3 months of life. Crying usually peaks at 6 weeks and abates by 12–16 weeks.

For most irritable infants, there is no underlying medical cause. In a minority, the cause is cow’s milk and other food allergy. Only if frequent vomiting (about five times a day) occurs is gastro-oesophageal reflux a likely cause.

It is important to assess the mother–infant relationship and maternal fatigue, anxiety and depression.

Management of excessive crying includes:

explaining babies’ normal crying and sleeping patterns;

helping parents help their baby deal with discomfort and distress through a baby-centred approach;

helping parents recognise when their baby is tired and apply a consistent approach to settling their baby;

encouraging parents to accept help from friends and family, and to simplify household tasks.

If they are unable to manage their baby’s crying, admission to a parenting centre (day stay or overnight stay) or local hospital should be arranged.