Clinical Record

A 30-year-old woman in the 30th week of pregnancy was admitted with a two-day history of fever, malaise, dysuria, frequent micturition and mild lower abdominal pain. Slight lower abdominal tenderness was the only clinical abnormality. Results of urine microscopy were white blood cell (WBC) count, 33 × 106/L (normal range, 0–10); red blood cell count, 15 × 106/L (normal range, 0–12); epithelial cell count, 21 × 106/L (normal range, 0–5); and culture was sterile. Full blood count revealed haemoglobin, 113 g/L (normal range, 100–180); WBC count, 11.6 × 109/L (normal range, 5–18); platelet count, 215 × 109/L (normal range, 150–450); and lymphocyte count, 0.23 × 109/L (normal range, 2–8). Liver function tests were mildly abnormal at presentation (Table).

The patient was treated with empirical ampicillin and gentamicin, with resolution of her symptoms. However, her liver function tests worsened. Leptospiral serology was negative and blood cultures were sterile. Hepatitis A, B and C, flavivirus, Ross River virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, HIV, parvovirus and toxoplasmosis were all excluded. Negative antinuclear, mitochondrial and smooth muscle antibodies and normal immunoglobulin levels indicated that autoimmune hepatitis was unlikely.

From the fifth day after admission, her condition deteriorated, with marked upper abdominal pain and worsening liver function tests (Table). On admission to the intensive care unit she was confused, febrile (37.5°C) and tachycardic (112/min). Blood pressure was 105/70 mmHg and results of cardiorespiratory examination were normal. Right hypochondrial tenderness was present. There were no clinical stigmata of hepatic decompensation. Results of laboratory tests (Day 7) were international normalised ratio of prothrombin time, 1.7 (normal, < 1.2); lymphocyte count, 0.57 × 109/L; leukocyte count, 3.1 × 109/L; and liver function tests as shown in the Table. Renal function and platelet counts were normal.

Delivery was deemed necessary to preserve the baby's life. A live baby was delivered by caesarean section (Day 10). There were no orogenital lesions on the mother. The baby was well, with no clinical abnormalities.

After the caesarean section, the patient remained stable for 24 hours and then suffered progressive circulatory insufficiency. Despite escalating doses of vasopressors, she developed renal failure. Bilateral pneumonia and pleural effusions led to respiratory failure, and the patient was intubated for assisted mechanical ventilation. Results of liver function tests (Table) confirmed worsening of disordered hepatic synthesis, progressive hepatocellular injury and coagulopathy. An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed gross hepatomegaly, with diffuse low attenuation of the left lobe of the liver and mottling of the right lobe of the liver.

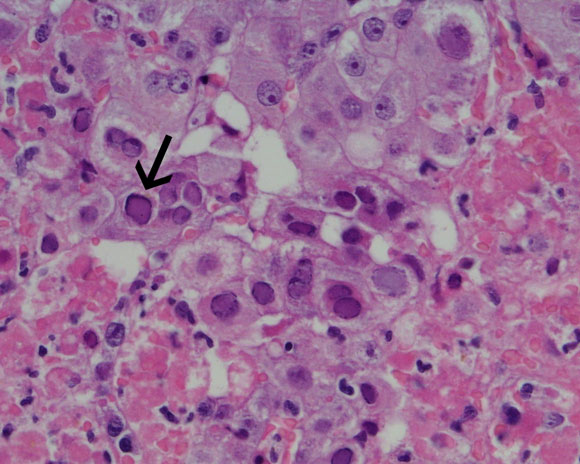

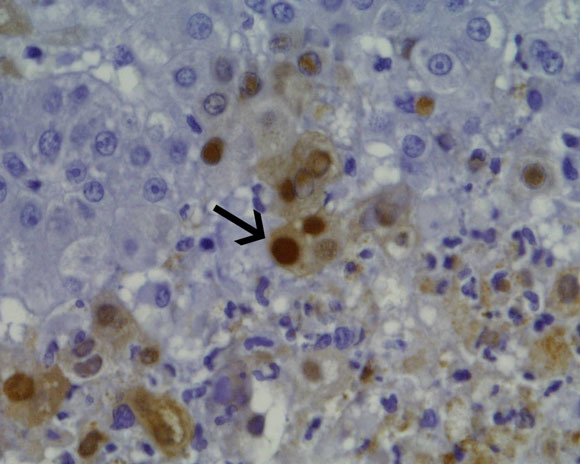

Liver biopsy, precluded by coagulopathy during the caesarean section, was accomplished on Day 13. Histology revealed hepatic necrosis, with 40%–50% of the hepatic parenchyma showing haemorrhagic necrosis with a neutrophilic infiltrate (Box 1A). At the interface between necrotic areas and surviving parenchyma, many liver cells showed glazed amphophilic chromatin consistent with herpesvirus inclusions. Polyclonal herpes simplex virus immunoperoxidase stain showed strong nuclear staining in these cells (Box 1B). Polymerase chain reaction testing of her serum subsequently revealed herpes simplex virus (HSV) DNA and HSV 2 was cultured from a vaginal swab.

The patient was treated with intravenous aciclovir (750 mg every 8 h), but remained critically ill, with persistent circulatory shock, anuric renal failure and fulminant hepatic failure. Enterococcus faecalis bacteraemia compounded her shock. On Day 25, she died of fulminant hepatitis and multiorgan failure.

Autopsy revealed severe hepatic architectural distortion, with almost complete absence of portal tracts and central veins. The necrotic foci were more extensive than those seen at biopsy. HSV immunohistochemical stain showed cytoplasmic staining. Interstitial pneumonitis and autolysis of the kidneys were seen, with no evidence of glomerulonephritis. Viral inclusions were seen only in the liver.

Her infant was treated empirically with aciclovir and is growing and developing normally.

Days after admission |

|||||||||||

Normal range |

1 |

4 |

7 |

10 |

13 |

16 |

19 |

25 |

|||

Serum aspartate transaminase (U/L) |

7–56 |

66 |

919 |

1738 |

3814 |

2499 |

1592 |

144 |

103 |

||

Serum alanine transaminase (U/L) |

7–56 |

62 |

558 |

522 |

700 |

443 |

335 |

77 |

25 |

||

Bilirubin (µmol/L) |

< 17 |

8 |

10 |

11 |

24 |

47 |

68 |

400 |

600 |

||

Albumin (g/L) |

35–45 |

20 |

15 |

12 |

17 |

14 |

15 |

18 |

16 |

||

Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) |

30–120 |

123 |

333 |

378 |

471 |

345 |

294 |

155 |

125 |

||

Serum γ-glutamyltransferase (U/L) |

10–75 |

16 |

76 |

105 |

126 |

100 |

71 |

28 |

25 |

||

Many pregnancy-specific liver disorders occur in the third trimester; thus, an aetiological diagnosis of liver diseases can be difficult. Common liver disorders in pregnancy are intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets), and acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

The commonest cause of jaundice in pregnancy is acute viral hepatitis, which can result from primary infections with hepatitis viruses A to E or as part of a systemic infection with viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV).1 Except when caused by hepatitis E virus or HSV, viral hepatitis does not usually increase maternal or fetal mortality.2

Hepatitis due to HSV infection is a rare but frequently fulminant disease. Most reports have been in immunocompromised patients3 or newborns.4 Fulminant HSV hepatitis has been reported in immunocompetent adults,5-7 mostly pregnant women.8-10 Two per cent of susceptible women acquire HSV infection during pregnancy, and seroconversion can be asymptomatic.6

Most reported cases of HSV hepatitis followed a primary orogenital infection with HSV type 1 or 2.5,8-10 As in our patient, the reported cases included initially normal serum bilirubin levels, markedly elevated serum transaminase levels, and very high AST/ALT ratios.

In our patient, liver histology and immunohistochemistry established the diagnosis. Serology, PCR and vaginal swab cultures were complementary.

Early administration of aciclovir has been successful in treating HSV hepatitis.5,7 Liver transplantation is another treatment option,11 but the risk of recurrent HSV hepatitis with overwhelming viral dissemination and concurrent enterococcal sepsis were contraindications in our patient.

A high index of suspicion for HSV infection is warranted, as hepatitis can occur without orogenital herpetic lesions. HSV serology, PCR testing for HSV DNA, and vaginal swab cultures are recommended in undifferentiated liver disorders. Liver biopsy should be considered in patients with hepatitis when a definitive aetiology is elusive. Empirical treatment with aciclovir should be considered.

- Ramesh Nagappan1

- Geoffrey Parkin2

- Ian Simpson3

- William Sievert4

- Monash Medical Centre, Clayton, VIC.

- 1. Williams R, Riordan SM. Acute liver failure: established and putative hepatitis viruses and therapeutic implications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 15 Suppl: G17-G25.

- 2. Hunt CM, Sharara AI. Liver disease in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 1999; 59: 829-836.

- 3. Johnson JR, Egaas S, Gleaves CA, et al. Hepatitis due to herpes simplex virus in marrow-transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14: 38-45.

- 4. Hufert FT, Diebold T, Ermisch B, et al. Liver failure due to disseminated HSV-1 infection in a newborn twin. Scand J Infect Dis 1995; 27: 627-629.

- 5. Velasco M, Llamas E, Guijarro-Rojas M, Ruiz-Yague M. Fulminant herpes hepatitis in a healthy adult: a treatable disorder? J Clin Gastroenterol 1999; 28: 386-389.

- 6. Brown ZA, Selke S, Zeh J, et al. The acquisition of herpes simplex during pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 509-515.

- 7. Kaufman B, Gandhi SA, Louie E, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24: 334-338.

- 8. Johnson LG, Saldana LR. HSV hepatitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med 1994; 39: 544-546.

- 9. Fink CG, Read SJ, Hopkin J, et al. Acute herpes hepatitis in pregnancy. J Clin Pathol 1993; 46: 968-971.

- 10. Yaziji H, Hill T, Pitman T, et al. Gestational herpes simplex virus hepatitis. South Med J 1997; 90: 347-351.

- 11. Shanley CJ, Braun DK, Brown K, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to herpes simplex virus hepatitis. Successful outcome after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation 1995; 59: 145-149.