Indigenous Australians have a markedly higher burden of disease and injury than the general Australian population.1 Most of this has been attributed to higher rates of non-communicable diseases, including mental disorders, but as there are no national data on the prevalence or incidence of diagnosed mental disorders for Indigenous people, proxy measures of relative rates have been used to estimate this component of the burden of disease.

Although there have been small studies of mental health in specific Indigenous communities over the past 50 years,2 the only national statistics that have been available until recently were the suicide rate,3 the hospitalisation rate for diagnosed mental disorders,3 emergency department attendances for mental health and substance misuse-related conditions3 and contacts with public community health services,4 which indicate a relative prevalence two or three times the corresponding general population rate. Even this is likely to be an underestimate, as many Indigenous people do not access regular health services, or delay seeking help until problems are severe.5

Community diagnostic surveys potentially give a fuller picture of the mental health status of the population. The 2003–2004 New Zealand Mental Health Survey oversampled Maori people and used the same interview to yield separate Maori and non-Maori prevalence rates,6 but the 1997 and 2007 Australian National Surveys of Mental Health and Wellbeing contained only a small incidental sample of Indigenous respondents, and separate data would have been too unreliable to be useful.7,8

A systematic search was conducted using the method outlined by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement.9 Studies were identified as eligible for inclusion if they:

included a sample of Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people;

employed representative sampling;

contained a measure of mental health;

were published, or the data were collected, from the year 2000 onwards; and

contained published or non-published survey data.

Studies were identified by searching electronic databases, reviewing known state and national health datasets and consulting with others working in the field. References from the initial search were also scanned for additional relevant studies. This search was applied to PubMed, PsycINFO, the Australian Medical Index, and the National Library of Australia for publications from 1 January 2000 to 22 September 2009. The following search terms were used to search electronic databases: Australian AND (Aboriginal OR Indigenous OR “Torres Strait Islander”) AND (anxiety OR depression OR distress OR mental OR “social emotional wellbeing”). The last search of electronic databases was run on 22 September 2009.

Studies from the initial search were excluded if the abstract and title showed they did not meet the eligibility criteria. The remainder were reviewed and selected for inclusion if they met the stated criteria. Two of us (S J B and A F J) reviewed the studies and came to a consensus decision about inclusion. If the same study had been published more than once, this was resolved by ensuring that data were reported consistently across publications, and then only including data from the report with the most detailed data.

The measures of psychological distress used in the studies located are outlined in Box 1.

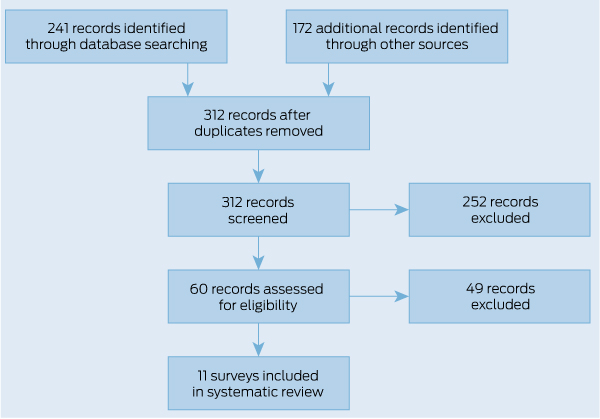

The PRISMA flow chart of included and excluded studies is shown in Box 2. We found eight surveys that used a self-report measure of psychological distress (Kessler Psychological Distress Scales [K10, K6, K5] or Mental Health Index [MHI5]).11,14-25 These studies involved either adolescents, adults or both. Four studies were designed specifically to assess health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.11,18,20,21 Seven of the studies provided non-Indigenous comparison data.11,14-20,22-25 In the six studies involving adults, the Indigenous population had a higher prevalence rate of high or very high psychological distress scores, ranging from about 50% to three times higher (overall rates, 20.2%–26.6%). A higher prevalence rate was found for Indigenous Australians of both sexes and of all adult age groups. By contrast, there were two surveys that provided data specifically on adolescents, neither of which found any difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous prevalence rates.15,21 Overall rates of very high psychological distress scores were 10%–11%. Box 3 (http://dx.doi.org/10.5694/mja11. 10041) summarises the findings of these studies.

We also found three surveys that reported data on Indigenous children and adolescents, using carer or teacher report with a variant of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).21,22,26 The two surveys of parents and carers found a higher prevalence of overall behaviour problems in Indigenous children.22,26 The survey using teacher reports did not find a difference, but had a sample biased towards wealthier Indigenous families.26 Only one of these surveys reported data by age group and sex, and this found a higher prevalence of behaviour problems among Indigenous young people of both sexes, and in both children and adolescents.21 That survey was also the only one to report on SDQ subscales.21 It found higher rates of Conduct Problems and Hyperactivity and, to a lesser degree, Peer Problems; however, there was no difference in Emotional Symptoms.21 Box 4 (http://dx.doi.org/10.5694/mja11.10041) summarises the findings of these studies.

The causes of these differences (and similarities) in mental health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians need to be explored, as has been done with the inequality in Indigenous physical health. With physical health, much of the gap has been found to be attributable to tobacco use, high body mass, physical inactivity, high blood cholesterol levels and alcohol misuse,1 but the role of mental ill health in health-related behaviours has not been explored.

Potential mediators of differences in psychological distress and consequential behaviour include unemployment, fewer educational qualifications, lower income, adverse life events, smoking and chronic physical illnesses. These factors have been found to correlate with psychological distress,27-30 and are experienced at higher rates by Indigenous people.5,11,16 Social disadvantage is also associated with behaviour problems among children.31 Such an analysis of mediators would allow better targeting and monitoring of preventive efforts for improving Indigenous mental health. We have attempted an analysis of socioeconomic mediators using data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, but this survey found a smaller Indigenous mental health gap than others and was not suitable for this purpose. These issues could be better explored in other datasets.11,16

The existing evidence has many limitations. One is the cultural appropriateness of the survey questionnaires. Indigenous concepts of mental health tend to be broader than psychological distress and behaviour problems, and are usually described using the term “social and emotional wellbeing”.11,32 Social and emotional wellbeing includes mental health and acknowledges the importance of factors beyond the individual, such as cultural identification, spirituality and the community. While the measures used here do not cover the entirety of this concept, the Kessler scales do cover an important component (psychological distress), and this component has been found to be related to number of days unable to work and number of visits to a health professional among Indigenous people.8 Less is known about the SDQ, but it has been reported to be culturally acceptable to clinicians working in Aboriginal health services in one region of Australia.33

The Kessler scales and the SDQ have been validated against diagnosis in samples of non-Indigenous Australians12,34,35 and in different cultures.36,37 However, this has not been done for Indigenous Australians. There is a major difficulty in carrying out such validation studies because no culturally acceptable diagnostic instrument exists, and there are considerable practical problems with adapting complex structured interviews across cultures,38 particularly if there are diverse Indigenous communities that must be accommodated.

Nevertheless, we argue that measures like the Kessler scales and the SDQ are useful indicators of mental health in their own right, which do not necessarily have to be linked to diagnostic outcomes. For example, K6 results similar to those reported here have been found for Native American and Alaska Native adults,39 and a United States study of the sociodemographic and health correlates of very high distress concluded that the K6 identified people with characteristics “the same as . . . persons with serious mental illnesses as described in psychiatric epidemiologic studies”.40 In addition, diagnostic concepts may be less acceptable to Indigenous people than scales measuring general psychological distress. Thus, for example, the Australian Indigenous Psychologists Association has built on survey data to outline a practical framework for evaluating social and emotional wellbeing that does not depend on diagnostic labelling at all.32

Survey methodologies also have limitations. Although most of the data were collected by personal interview and telephone interview, one study used written questionnaires,14 which may be problematic if people with poorer literacy are less likely to participate.41 Several surveys used telephone interviewing, which may produce biased sampling if the population includes remote residents. Thus, a telephone survey in the Northern Territory excluded most households in remote areas, and wealthier families were overrepresented.26 By contrast, in New South Wales, where telephone ownership is high, this methodology has been endorsed by Aboriginal community organisations and the samples do not appear to be biased when considered against other sources of data.17,23 Lastly, there is considerable diversity among Indigenous peoples in Australia,42 and findings from population surveys may not apply equally to all groups. In particular, none of the surveys reviewed reported data specific to Torres Strait Islander people.

1 Measures of mental health used in the surveys

Kessler Psychological Distress Scales (K10, K6, K5)

K10: a measure of the level of a person’s psychological distress; it does not attempt to identify specific mental illnesses.10 The K10 contains 10 items about non-specific psychological distress in the 4 weeks before interview. Scores range from 10 to 50.

K6: a six-item shortened version of the K10, yielding a score from 6 to 30.

K5: a culturally appropriate measure of psychological distress for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.11 The question “how much of the time have you felt worthless” was considered inappropriate to use in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, and was therefore removed. The K5 also contains slight wording changes to increase understanding in an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ is a brief behavioural screening questionnaire for children and adolescents.12 The SDQ asks about 25 attributes, which are considered strengths, difficulties or neutral. There are five subscales each with five items: Hyperactivity, Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Peer Problems and Prosocial Behaviour. Each subscale yields a score from 0 to 10. There is also a total score, which involves summing all the subscales except Prosocial Behaviour and yields a score from 0 to 40.

The MHI5 is a five-item measure of mental health that asks about symptoms in the past 4 weeks. It is part of the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short-Form (SF-36) Health Survey.13 Scores are rescaled to range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better mental health.

2 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart of included and excluded surveys

3 Summary of community surveys on the prevalence of self-reported mental health problems among Indigenous Australians

4 Summary of community surveys on the prevalence of carer- or teacher-reported mental health problems in Indigenous children and adolescents

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Anthony F Jorm1

- Sarah J Bourchier1

- Stefan Cvetkovski1

- Gavin Stewart2

- 1 Orygen Youth Health Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol Office, New South Wales Health Department, Sydney, NSW.

This work was supported by funding from a National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship and the Colonial Foundation. We used unit record data from the HILDA Survey. The HILDA Survey was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. The findings and views reported in this article are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the Institute.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Vos T, Barker B, Begg S, et al. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: the Indigenous health gap. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38: 470-477.

- 2. Swan P, Raphael B. Ways forward: national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health policy national consultancy report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1995.

- 3. Vos T, Barker B, Stanley L, Lopez AD. The burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2003. Brisbane: School of Population Health, University of Queensland, 2007.

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health services in Australia 2007–08. Canberra: AIHW, 2010. (AIHW Cat. No. HSE 88; Mental Health Series No. 12.)

- 5. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Social and emotional wellbeing (including mental health). http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-facts/overviews/selected-health-conditions/mental-health (accessed Jan 2011).

- 6. Wells JE, Oakley Browne MA, Scott KM, et al. Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey: overview of methods and findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006; 40: 835-844.

- 7. Henderson S, Andrews G, Hall W. Australia’s mental health: an overview of the general population survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000; 34: 197-205.

- 8. Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne MA, et al. 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009; 43: 594-605.

- 9. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000100.

- 10. Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 494-497.

- 11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: AIHW, 2009. (AIHW Cat. No. IHW 24.)

- 12. Hawes DJ, Dadds MR. Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004; 38: 644-651.

- 13. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473-483.

- 14. Butterworth P, Crosier T. The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: demonstrating the applicability of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health 2004; 4: 44.

- 15. Morgan A, Jorm A. Awareness of beyondblue: the national depression initiative in Australian young people. Australas Psychiatry 2007; 15: 329-333.

- 16. Australian Bureau of Statistics. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: ABS, 2010. (ABS Cat. No. 4704.0.)

- 17. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. 2002–2005 Report on adult Aboriginal health from the New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2006.

- 18. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. 2002–2005 Report on adult health by country of birth from the New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2006. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Public Health/surveys/hsa/0205cob/index.asp (accessed Nov 2010).

- 19. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. Report on adult health in New South Wales 2005. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2007. http://www. health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/surveys/hsa/05/index.asp (accessed Mar 2011).

- 20. Population Research and Outcome Studies Unit. A chartbook of the health and wellbeing status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in South Australia 2006. Adelaide: South Australian Department of Health, 2006.

- 21. Zubrick SR, Lawrence DM, Silburn SR, et al. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: the health of Aboriginal children and young people. Perth: Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 2004.

- 22. Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. The state of Victoria’s children 2009: Aboriginal children and young people in Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010.

- 23. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. 2006–2009 report on adult Aboriginal health in New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2010.

- 24. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. 2006–2009 report on adult health by country of birth from the New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2010. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/publichealth/surveys/hsa_0609cob_pdf.asp (accessed Mar 2011).

- 25. Centre for Epidemiology and Research. Report on adult health from the 2009 New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2011. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/surveys/hsa/09/index.asp (accessed Mar 2011).

- 26. Li SQ, Jacklyn SP, Carson BE, et al. Growing up in the Territory: social-emotional wellbeing and learning outcomes. Darwin: Department of Health and Community Services, 2006.

- 27. Phongsavan P, Chey T, Bauman A, et al. Social capital, socio-economic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 2546-2461.

- 28. Chittleborough CR, Winefield H, Gill TK, et al. Age differences in associations between psychological distress and chronic conditions. Int J Public Health 2011; 56: 71-80.

- 29. Oakley Browne MA, Wells JE, Scott KM, McGee MA; New Zealand Mental Health Survey Research Team. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44: 314-322.

- 30. Fragar L, Stain HJ, Perkins D, et al. Distress among rural residents: does employment and occupation make a difference? Aust J Rural Health 2010; 18: 25-31.

- 31. Davis E, Sawyer MG, Lo SK, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for mental health problems in 4-5-year-old children: Australian population study. Acad Pediatr 2010; 10: 41-47.

- 32. Kelly K, Dudgeon P, Gee G, Glaskin B. Living on the edge: social and emotional wellbeing and risk and protective factors for serious psychological distress among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Discussion Paper No. 10. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009.

- 33. Williamson A, Redman S, Dadds M, et al. Acceptability of an emotional and behavioural screening tool for children in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in urban NSW. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44: 894-900.

- 34. Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med 2003; 33: 357-362.

- 35. Mathai J, Anderson P, Bourne A. Comparing psychiatric diagnoses generated by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire with diagnoses made by clinicians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004; 38: 639-643.

- 36. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MI, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010; 19 Suppl 1: 4-22.

- 37. Mullick MS, Goodman R. Questionnaire screening for mental health problems in Bangladeshi children: a preliminary study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001; 36: 94-99.

- 38. Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P; AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Cult Med Psychiatry 2003; 27: 259-289.

- 39. Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the American Indian and Alaska Native adult population: United States, 1999–2003. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics no. 356: 1-22. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics, 2005.

- 40. Pratt LA, Dey AN, Cohen AJ. Characteristics of adults with serious psychological distress as measured by the K6 scale: United States, 2001–04. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics no. 382. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007.

- 41. Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision. Overcoming indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2009. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2009.

- 42. Walter M. Lives of diversity: Indigenous Australia. Canberra: Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, 2008. (Occasional Paper Series no. 4/2008.)

Abstract

Objective: To assemble what is known about the mental health of Indigenous Australians from community surveys.

Data sources: A systematic search was carried out of publications and data sources since 2000 using PubMed, PsycINFO, Australian Medical Index, the National Library of Australia and datasets known to the authors.

Study selection: Surveys had to involve representative sampling of a population, identify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and include a measure of mental health.

Data extraction: 11 surveys were found. Data were extracted on prevalence rates for Indigenous people by age and sex, along with comparison data from the general population, where available.

Data synthesis: Across seven studies, Indigenous adults were consistently found to have a higher prevalence of self-reported psychological distress than the general community. However, two studies of Indigenous adolescents did not find a higher prevalence of psychological distress. Two surveys of parents and carers of Indigenous children and adolescents found a higher prevalence of behaviour problems.

Conclusions: There is an inequality in mental health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians that starts from an early age. This needs to be a priority for research, preventive action and health services.