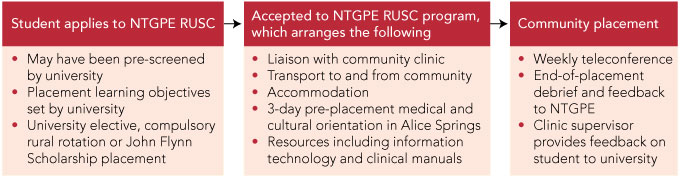

Through its Rural Undergraduate Support and Coordination Program (RUSC), Northern Territory General Practice Education (NTGPE) is responsible for 2–8-week elective placements undertaken by medical students from around Australia in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory (Box 1). Most students report high levels of satisfaction with their experience (unpublished data, NTGPE, 2006), and these placements are highly sought after.1

The literature on international electives suggests they promote the uptake of general practice; encourage doctors to work in public health and with underserved populations; and provide benefits to students’ personal and professional development.2-4 However, there are also concerns about the risks, which include important ethical issues for patients as well as students.5 If students work beyond their experience and are “expected to diagnose and treat patients without direct supervision from a qualified doctor”,6,7 patients may be placed at risk. This raises difficult questions. Is some care better than no care?8 Is the student the “most qualified” health care worker present to fulfil the patient’s right to quality care? The personal safety of the student is also crucial; in remote locations, students are at greater risk of accidents, infectious diseases, personal violence and even political threats.9

Ethics approval was obtained from the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee.

We used an educational institution-based definition of a “critical incident”10 to develop a student placement-specific definition of an incident as: an event, or the threat of one, which may

cause, or is likely to cause, significant physical and/or emotional distress or harm to the student experiencing or witnessing the event

be regarded as outside the normal range of experience of the persons affected

threaten, disrupt or prevent the ordinary functioning of the student placement.

Two subgroups were identified:

Clinical: events related to medical or clinical work by the student or other clinicians, or to patient morbidity and mortality (eg, accidental, avoidable or traumatic deaths or suicides; near-misses; needle-stick injuries; lack of supervision judged necessary for student competence; improper or negligent practice).

Non-clinical: events outside the direct medical, patient-related work of the student or clinic (eg, motor vehicle accidents; physical or verbal assault; bullying or harassment; extreme weather conditions; cultural transgressions; culture shock).

Face validation of cases was achieved by independent file review by two other staff (M V and H T N), who assessed whether the identified case met the agreed definition of an incident. Broad descriptors were developed to categorise the cases by common themes (Box 2). The three reviewers independently recorded which descriptors they thought best applied to each case. There was no discussion of which descriptors were applied by each reviewer, and each descriptor could therefore be applied multiple times to a case.

A total of 31 files with possible critical incidents were identified on initial screening. After face validation by the three investigators, six needed review; three were discarded, leaving a total of 28 identified cases (17% of all placements). There was a preponderance of female students placed, and this was proportionately represented in the incidents (Box 3).

Thematic analysis of the 28 cases found that clinical supervision, professional practice and administration were the key issues causing distress for the students (Box 4). A small sample of cases is described in Box 5.

Personal qualities such as resourcefulness, self-confidence and cross-cultural skills will aid students in making the most of their elective. However, a “medical tourist” attitude may undermine the learning component and lead to mismatched expectations. Some students may be experiential learners and “keen to have a go”; they may appreciate a lack of supervision as it allows them to do more, but they may lack insight into their own capabilities and have “strategies to appear as competent as possible”.11,12 All these attitudes and perceptions can challenge the inexperienced supervisor.

A review from the United Kingdom recognised the value of more structured approaches to medical electives to maximise learning and minimise the risks.13 Strategic planning can address some of the challenges of clinical education14 in the primary care and remote Aboriginal community setting, and should be applied to student electives. Immediate strategies can include organisational systems for risk management; staff and student commitment to processes such as ethical practice; feedback and debriefs; and employing staff who are familiar with local conditions. Establishing more intimate partnerships with communities, universities and clinics with stable staffing, developing rigorous standards for selection of supervisors, and resourcing interprofessional training in clinical education are some longer-term practical strategies.

1 Northern Territory General Practice Education (NTGPE) Rural Undergraduate Support and Coordination Program (RUSC) process

2 Descriptors for potentially harmful incidents

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Ameeta Patel1

- Peter Underwood2,3

- Hung The Nguyen2

- Margaret Vigants2

- 1 Bath Street Family Medical Practice, Alice Springs, NT.

- 2 Northern Territory General Practice Education, Darwin, NT.

- 3 University of Western Australia, Perth, WA.

We gratefully acknowledge the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Research Foundation for its support of this project, which was funded by an RACGP/APHCRI (Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute) Indigenous Health Award. We also acknowledge the medical students, Aboriginal communities and clinicians who participate in the NTGPE student placement program.

None identified.

- 1. Smith JD, Wolfe C; RhED Consulting. NT review of medical education and training: final report. Darwin: NT Department of Health and Community Services, 2007. http://www.health.nt.gov.au/library/scripts/objectifyMedia.aspx?file=pdf/6/92.pdf (accessed Dec 2010).

- 2. Imperato PJ. A third world international health elective for US medical students: the 25-year experience of the State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center. J Community Health 2004; 29: 337-373.

- 3. Ramsey AH, Haq C, Gjerde CL, Rothenberg D. Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam Med 2004; 36: 412-416.

- 4. Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med 2000; 32: 566-572.

- 5. Pinto AD, Upshur RE. Global health ethics for students. Dev World Bioeth 2009; 9: 1-10.

- 6. Radstone SJ. Practising on the poor? Healthcare workers’ beliefs about the role of medical students during their elective. J Med Ethics 2005; 31: 109-110.

- 7. Banatvala N, Doyal L. Knowing when to say “no” on the student elective [editorial]. BMJ 1998; 316: 1404-1405.

- 8. Bhat SB. Ethical coherency when medical students work abroad. Lancet 2008; 372: 1133-1134.

- 9. Tyagi S, Corbett S, Welfare M. Safety on elective: a survey on safety advice and adverse events during electives. Clin Med 2006; 6: 154-156.

- 10. Charles Sturt University critical incident management handbook. September 2006: 11. http://www.csu.edu.au/division/facilitiesm/services/docs/critical-incident-management-hbook.pdf (accessed Dec 2010).

- 11. Kilminster SM, Jolly BC. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review. Med Educ 2000; 34: 827-840.

- 12. Shah S, Wu T. The medical student global health experience: professionalism and ethical implications. J Med Ethics 2008; 34: 375-378.

- 13. Dowell J, Merrylees N. Electives: isn’t it time for a change? Med Educ 2009; 43: 121-126.

- 14. Gordon J, Hazlett C, Ten Cate O, et al. Strategic planning in medical education: enhancing the learning environment for students in clinical settings. Med Educ 2000; 34: 841-850.

Abstract

Objective: To assess the number and characteristics of potentially harmful incidents occurring during placement of medical students in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory.

Design, participants and setting: A retrospective audit of medical students’ files from Northern Territory General Practice Education placements in Central Australia for the period from January 2006 to December 2007.

Main outcome measures: Number and type of potentially harmful incidents.

Results: A total of 163 placements were undertaken. Of these, 98 (60%) had adequate documentation to determine whether an incident had occurred. There were 28 cases (17%) where potentially harmful incidents were judged to have occurred. Most incidents fell under several descriptive categories, but clinical supervision, professional practice and administrative issues were most common.

Conclusions: One in six students experienced a potentially harmful incident during remote area placement in 2006–2007. While acknowledging the exploratory nature of this investigation and the major educational benefits that clearly arise from these placements, our findings indicate problems with clinical supervision and administration.