With community involvement, research can be a powerful tool for closing the gap in Indigenous health disparity

Now, in the first decades of a new millennium, it is exciting and energising to find so many voices and forums converging to provide new perspectives on knowledge. At the Lowitja Institute, Australia’s National Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research, we see this as a unique opportunity to achieve positive, lasting change in the health and wellbeing of Australia’s first peoples.

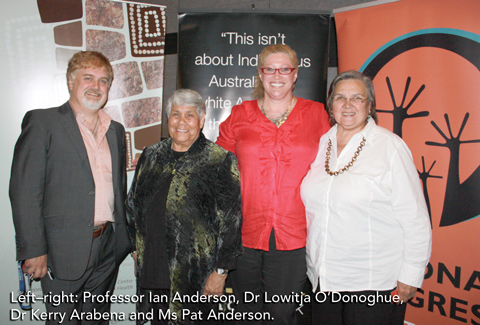

It is both an honour and a challenge to implement this research agenda with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health leaders Dr Lowitja O’Donoghue, Ms Pat Anderson and Professor Ian Anderson. We are supported in this by our 12 national partners, which include community-controlled health services, state, territory and federal government departments, and academic research institutions (see http://www.lowitja.org.au/crcatsih-participants for details).

Health professionals are well aware that, despite all the research and the medical interventions spanning decades, improvements — where they occur — are incremental and trend up at a slower rate than for non-Indigenous Australians. For example, while the most recent figures show life expectancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is improving, so is the life expectancy of other Australians,1 meaning that the ideal of closing the life expectancy gap within a generation is, in effect, an ever-receding target.

As Australia’s only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-controlled pure health research organisation, the Lowitja Institute is focused on precisely this conundrum. A growing body of research tells us that, in order to nurture the physical body, we must also bolster the social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing of people who have been adversely affected by over 200 years of colonisation, dispossession and marginalisation.2,3 Other research shows that having Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples involved in all aspects of research and health infrastructure is crucial to success.4,5 In other words, a doctor can heal broken bones, but Indigenous peoples need to be engaged in creating the diversity of choices and responses to issues affecting their lives; issues that remain well beyond the reach of the surgeon’s scalpel.

While the Northern Territory National Emergency Response has highlighted the appalling health and living conditions of Aboriginal people in remote areas, the lack of social capital, amenities and health infrastructure is only part of the story. For even when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples live in well resourced urban and regional areas, as most now do, their health and wellbeing is still, on average, substantially worse than that of their non-Indigenous neighbours on the other side of the fence.6

This approach has proved highly successful, as shown by the outcomes of research projects that have led to improvements in the way many hospitals liaise with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients;7,8 improvements in the management of Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations;9 more closely targeted interventions aimed at the underlying causes of ill health, such as scabies infestations and smoking;10,11 and a growing awareness of the inefficiency of current funding arrangements for Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations.12 In fact, this approach has been so successful that the CRCAH is one of only four CRCs ever to succeed in winning a third round of federal funding.

This brings us to the here and now, and the future as encapsulated by the Lowitja Institute.

Real Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership.

Full involvement from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and organisations in the initiation, design and implementation of research.

Building Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation at all levels of the health system.

Mentoring and support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers.

Wide dissemination of research findings to all research users.

Strong engagement with government and private enterprise, but without compromising core principles.

Currently, eight research projects are underway across our three program areas, with many more in the pipeline. The support we provide can include both financial and facilitation assistance, by ensuring a strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander presence in all project leadership teams and that the research is appropriately and widely communicated. Capacity-building initiatives are embedded within all projects, providing support to students and budding researchers through collaborations with some of Australia’s leading educational and training organisations. We also have a strong foundation built on partnerships with other organisations right across the health sector, especially through Congress Lowitja, our principal stakeholder body, which meets biennially (http://www.lowitja.org.au/congress-lowitja).

Provenance: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Closing the Gap. Prime Minister’s report 2011. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2011: 12.

- 2. Kelly K, Dudgeon P, Gee G, Glaskin B. Living on the edge: social and emotional wellbeing and risk and protective factors for serious psychological distress among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. (Discussion Paper No. 10.) Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009.

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. (AIHW Cat. No. IHW 24.) Canberra: AIHW, 2009.

- 4. Anderson IPS. The knowledge economy and Aboriginal health development [Dean’s lecture, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, 13 May 2008]. Melbourne: Onemda VicHealth Koori Health Unit, University of Melbourne, 2008.

- 5. Lawson KA, Armstrong RM, Van Der Weyden MB. Training Indigenous doctors for Australia: shooting for goal. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 547-550. <MJA full text>

- 6. Vos T, Barker B, Stanley L, Lopez AD. The burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2003. Brisbane: School of Population Health, University of Queensland, 2007.

- 7. Lawrence M, Dodd Z, Mohor S, et al. Improving the patient journey: achieving positive outcomes for remote Aboriginal cardiac patients. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009. http://www.lowitja.org.au/crcah/list-crcah-publications (accessed Mar 2011).

- 8. Willis J, Wilson G, Renhard R, et al. Improving the culture of hospitals project: final report. Melbourne: Australian Institute for Primary Care, La Trobe University, 2010.

- 9. One21seventy: National Centre for Quality Improvement in Indigenous Primary Health Care [website]. http://www.one21seventy.org.au (accessed Mar 2011).

- 10. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health. Healthy Skin Program. http://www.lowitja.org.au/crcah/crcah-research-projects#HSRP (accessed Mar 2011).

- 11. Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Tobacco Control. Indigenous tobacco control in Australia: everybody’s business. National Indigenous Tobacco Control Research roundtable report. Brisbane; 2008; May 23. Melbourne: CEITC, University of Melbourne, 2008.

- 12. Dwyer J, O’Donnell K, Lavoie J, et al. The overburden report: contracting for Indigenous health services. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009. http://www.lowitja.org.au/crcah/list-crcah-publications (accessed Mar 2011).

None identified.