The Victorian bushfires in February 2009 rank second among Australia’s worst natural disasters (Box 1)1 and among the top 10 wildfires/bushfires in the world with respect to fatalities (Box 2).2 Before the “Black Saturday” fires of February 2009, bushfires in Australia had resulted in 642 recorded deaths.3 Despite these tragedies, little has been published on bushfires (wildfires or firestorms), associated patient demographics and emergency medical responses.

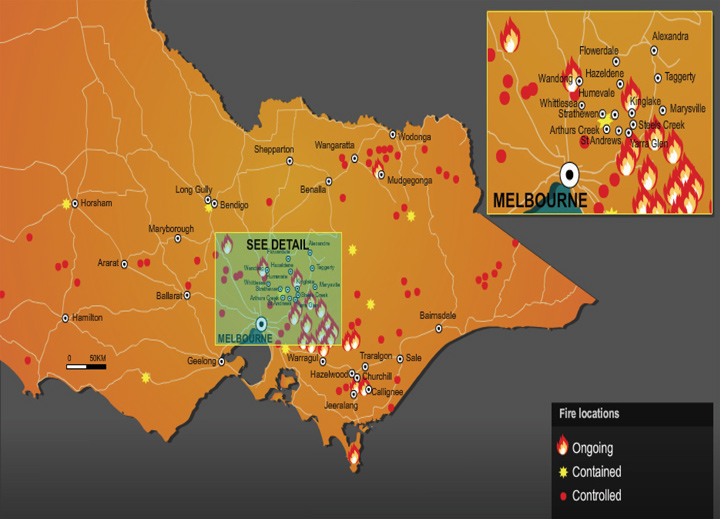

On Saturday 7 February 2009, the state of Victoria experienced its hottest day on record, with the temperature in Melbourne reaching 46.4°C (116°F). Bushfires that had started in the heat across the state on that day intensified as a cool change came through in the afternoon, backed by winds gusting at up to 100 km/h. The major fires occurred in 14 different geographical regions and burnt an area of over 350 000 hectares (Box 3).

As part of its state emergency management arrangements, the state of Victoria has a mass casualty burns plan that aims to provide a clear framework for optimal care of burns survivors of a mass casualty incident.4 The state response is linked in with a national burns plan (AUSBURNPLAN).5 The importance of disaster planning exercises has been established,6 and practice exercises have been conducted throughout the state.7 The Black Saturday event represented an opportunity to critically examine the state’s medical disaster response.

Victoria is serviced by a statewide trauma system that includes two adult major trauma centres in central Melbourne (Royal Melbourne Hospital and The Alfred Hospital [The Alfred]) and one paediatric major trauma and burns centre (Royal Children’s Hospital).8 The state’s adult burns service is located at The Alfred.

In non-mass-casualty situations, a burn of over 10% of total body surface area (TBSA) is considered an indication for admission to a specialist burns unit.9 The Victorian State Trauma System, AUSBURNPLAN5 and the Victorian mass casualty burns plan4 define a severe burn as a burn to 20% or more of TBSA in adults and children.

AUSBURNPLAN,5 yet to be ratified, was nationally activated by the Victorian Department of Human Services and the Australian Government. As part of this response, Emergency and Trauma Services at the Royal Melbourne Hospital agreed to accept all other adult trauma patients as well as major burns patients if The Alfred reached capacity. Medical directors of interstate burns units were notified of the possibility of a mass burns casualty event in Victoria. As part of the State Health Emergency Response Plan activation, contact was also established with Victoria’s Ambulance Emergency Operations Centre, which assisted in the prehospital triage.

Presentations to the major burns referral centres and bushfire-related presentations to surrounding hospitals within the first 72 hours are summarised in Box 4. There were 20 presentations to the E&TC for bushfire-related injuries — 11 primary presentations and nine transfers from other centres (Box 5). Eighteen patients had burn injuries. Fourteen of the 20 patients were men and six were women, with a median age of 53 years (IQR, 43–64 years) and a median Injury Severity Score of 13 (IQR, 4.0–27.5).

In the first 24 hours, nine patients went to theatre for wound debridement, escharotomies and dressing of partial-thickness wounds with Biobrane (Bertek Pharmaceuticals Inc), a synthetic skin substitute. Theatre times required for surgical procedures on burns patients in the first 72 hours are summarised in Box 6.

There have been few reports on acute medical responses to bushfires. Carroll and Raiter reported on the 1918 Cloquet Fire in Minnesota,10 while more recently Richardson and Kumar reported on the 2003 Canberra bushfires11 and Vilke and colleagues on the firestorm in San Diego County, California, in 2003.12 All three reports commented on the weaknesses in previous planning, and especially on the large numbers of patients presenting with minor injuries.

The capacity of Australian hospitals to respond to disasters has previously been questioned.13,14 A major feature of the response to the February 2009 Victorian bushfires was effective prehospital triaging. This enabled the state’s major referral centres to maintain considerable surge capacity. Other factors contributing to the relatively small numbers of injured patients presenting to the major trauma centres and statewide burns services included the presence of a rehearsed major burns plan, early communication, the significant distance of the major referral centres from the bushfires (thus enabling effective triage and minimising “walk-ins”), and a large number of supportive surrounding hospitals. Although TBSA ≥ 30% was set as the initial triage criterion for referral to the major burns centres when the total number of burns victims was unknown, this was not followed, as it became apparent that the number of surviving victims was significantly less than first estimated. The value of varying normal criteria for referral to a burns centre requires further discussion, as patients may be disadvantaged by delayed referral.

There have been multiple reports on the stresses placed on burns centres during the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States.15,16 In a worst-case scenario,5 Australia may need to be able to cope with a surge capacity of up to 300 severely burn-injured patients, in addition to the background incidence of severe burn injury (about 50 cases per week nationally). The AUSBURNPLAN template directs that each state and territory have a burns/mass casualty disaster plan to manage any acute surge of patients locally within the template. In a large-scale disaster, the Australian Health Disaster Management Policy Committee should play a key consultative role by liaising with all key stakeholders.

The early deaths in this disaster were most likely from direct effects of the fires, flames and radiant heat. There is little information regarding the effects of improvements in prevention and early warning systems on the patterns of burn injuries from bushfires. However, evidence from other natural disasters suggests that improved early warning systems would result in lower mortality and a higher number of patients reaching hospitals, with lower overall deaths.17-21 It is hoped that the mortality profile from future bushfires will change in a similar way.

Our study was limited in that the data were not verified from all sites. It was unlikely that surgery for burns was performed outside the major burns referral centres, but this could not be confirmed. Examining the immediate impact on the primary care sector, which has been shown to be substantial in the past,22 was beyond the scope of our report. Significant psychological effects of bushfires have been previously reported23 and will require continued surveillance.

There are subtle differences between traditional management of major burns and management in the setting of a mass casualty disaster. The reception and resuscitation of the burns patients at The Alfred in February 2009 followed a standard approach (Box 7). As expected, most patients were hypovolaemic, and initial fluid resuscitation addressed this.24 Wound management was performed according to standard practice, but on a much larger scale. First aid measures included the use of Burn Aid (Rye Pharmaceuticals) or plastic cling wrap to cover burn wounds before definitive wound assessment could be carried out by medical and nursing staff. In view of uncertainty regarding total numbers of patients and the extent of injuries, there were some variations from usual early operative management practice:

Usual surgical practice (immediate transfer to the operating theatre for excision of burn wounds and wound closure with skin substitutes) was not instituted.

Patients with a coherent history, clean partial-thickness burn wounds of < 10% TBSA and no history of dam immersion had their wounds cleaned and dressed in the E&TC. Escharotomies were performed in the E&TC on unconscious patients.

Patients with extensive or contaminated burn wounds were transferred to the operating theatre for wound debridement, escharotomies and dressings.

Definitive surgical management was planned and instituted once all patients for whom it was indicated had undergone “damage control” surgery (completed within the first 24 hours).

Lessons from the February 2009 tragedy (Box 8) as well as previous natural disasters must be used to strengthen prevention and medical response systems.

4 Bushfire-related emergency department presentations within the first 72 hours of the Victorian bushfires*

5 Major burns and trauma presentations in the first 24 hours of the Victorian bushfires

| |||||||||||||||

|

* One patient with non-bushfire-related severe burns was admitted to The Alfred intensive care unit. | |||||||||||||||

6 Theatre times required for surgical procedures on burns patients at The Alfred Hospital in the first 72 hours of the Victorian bushfires

7 Major burns reception and resuscitation principles

8 Lessons from the February 2009 Victorian bushfires

Bushfire disasters are characterised by high mortality and relatively few survivors with serious burn injuries. This is important in planning a disaster response.

Prehospital triage is essential in managing the large number of minor ailments to avoid overloading the major burns centres.

Ensuring the involvement of senior experienced personnel at the major burns centres enables rapid assessment and management.

Even low numbers of patients with serious burns require substantial surgical resources during the first 72 hours.

The Victorian State Trauma System and state burns plan allow reallocation of trauma and emergency patients, ensuring substantial surge capacity at major referral centres.

The national burns plan (AUSBURNPLAN) provides further interstate surge capacity in the setting of larger disasters.

Received 22 February 2009, accepted 1 April 2009

- Peter A Cameron1

- Biswadev Mitra1,2

- Mark Fitzgerald2

- Carlos D Scheinkestel2

- Andrew Stripp2

- Chris Batey2

- Louise Niggemeyer2

- Melinda Truesdale3

- Paul Holman4

- Rishi Mehra2

- Jason Wasiak2

- Heather Cleland2

- 1 Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 4 Specialist Emergency Response Department, Ambulance Victoria, Melbourne, VIC.

We would like to thank the following people for their assistance in data collection: Steve White, The Alfred Trauma Registry; Graham Bushnell, The Alfred Clinical Performance Unit; Helen Stergiou, The Northern Hospital; Peter Archer, Maroondah Hospital; Sol Zalstein, Bendigo Health Service; Donna Gilmore, The Austin Hospital; Simon Young and Peter Barnett, the Royal Children’s Hospital; Alastair Meyer, Casey Hospital; and George Braitberg, Southern Health. We would also like to acknowledge all the volunteers and paramedical, medical, nursing and support staff who contributed to care of bushfire victims. Peter Cameron and Biswadev Mitra are supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

None identified.

- 1. Reuters. FACTBOX — Australia’s worst natural disasters. 8 Feb 2009. http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSSYD99754 (accessed Feb 2009).

- 2. Wikipedia. List of natural disasters by death toll. Top 10 deadliest wildfires and bushfires. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_natural_disasters_by_death_toll (accessed Feb 2009).

- 3. Emergency Management Australia, Attorney-General’s Department. EMA disasters database. Events by category. http://www.ema. gov.au/ema/emadisasters.nsf (accessed Feb 2009).

- 4. Victorian Government Emergency Management Branch. Victorian mass casualty burns plan. Melbourne: Department of Human Services, 2006. http://www.dhs.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/69791/burns_subplan_2006.pdf (accessed May 2009).

- 5. Cooper D. AUSBURNPLAN strategy paper. Australian mass casualty burn disaster plan. Final draft. Canberra: Australian Health Ministers’ Conference National Burns Planning and Coordinating Committee, 2004. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/DAEE022595059595CA25742F00069124/$File/ausburn.pdf (accessed Feb 2009).

- 6. Ginter PM, Duncan WJ, Abdolrasulnia M. Hospital strategic preparedness planning: the new imperative. Prehosp Disaster Med 2007; 22: 529-536.

- 7. Bartley BH, Stella JB, Walsh LD. What a disaster?! Assessing utility of simulated disaster exercise and educational process for improving hospital preparedness. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006; 21: 249-255.

- 8. Atkin C, Freedman I, Rosenfeld JV, et al. The evolution of an integrated state trauma system in Victoria, Australia. Injury 2005; 36: 1277-1287.

- 9. Australian and New Zealand Burns Association. Early management of severe burns. Course manual. 5th ed. Melbourne: ANZBA, 1999.

- 10. Carroll FM, Raiter FR. “At the time of our misfortune”: relief efforts following the 1918 Cloquet fire. Minn Hist 1983; 48: 270-282.

- 11. Richardson DB, Kumar S. Emergency response to the Canberra bushfires. Med J Aust 2004; 181: 40-42. <MJA full text>

- 12. Vilke GM, Smith AM, Stepanski BM, et al. Impact of the San Diego county firestorm on emergency medical services. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006; 21: 353-358.

- 13. Rosenfeld JV, Fitzgerald M, Kossmann T, et al. Is the Australian hospital system adequately prepared for terrorism? Med J Aust 2005; 183: 567-570. <MJA full text>

- 14. Traub M, Bradt DA, Joseph AP. The Surge Capacity for People in Emergencies (SCOPE) study in Australasian hospitals. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 394-398. <MJA full text>

- 15. Yurt RW, Bessey PQ, Alden NE, et al. Burn-injured patients in a disaster: September 11th revisited. J Burn Care Res 2006; 27: 635-641.

- 16. Jordan MH, Hollowed KA, Turner DG, et al. The Pentagon attack of September 11, 2001: a burn center’s experience. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005; 26: 109-116.

- 17. Alexander D. Natural disasters. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1993.

- 18. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Deaths associated with Hurricane Hugo — Puerto Rico. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1989; 38: 680-682.

- 19. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Deaths associated with Hurricanes Marilyn and Opal — United States, September–October 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1996; 45: 32-38.

- 20. Shultz JM, Russell J, Espinel Z. Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: the dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiol Rev 2005; 27: 21-35.

- 21. Sever MS, Vanholder R, Lameire N. Management of crush-related injures after disasters. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1052-1063.

- 22. Robinson M. Bushfires 2003. A rural GP’s perspective. Aust Fam Physician 2003; 32: 985-988.

- 23. McFarlane AC. The Ash Wednesday bushfires in South Australia. Implications for planning for future post-disaster services. Med J Aust 1984; 141: 286-291.

- 24. Mitra B, Fitzgerald M, Cameron P, Cleland H. Fluid resuscitation in major burns. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 35-38.

Abstract

Objective: To examine the response of the Victorian State Trauma System to the February 2009 bushfires.

Design and setting: A retrospective review of the strategic response required to treat patients with bushfire-related injury in the first 72 hours of the Victorian bushfires that began on 7 February 2009. Emergency department (ED) presentations and initial management of patients presenting to the state’s adult burns centre (The Alfred Hospital [The Alfred]) were analysed, as well as injuries and deaths associated with the fires.

Results: There were 414 patients who presented to hospital EDs as a result of the bushfires. Patients were triaged at the emergency scene, at treatment centres and in hospital. National and statewide burns disaster plans were activated. Twenty-two patients with burns presented to the state’s burns referral centres, of whom 18 were adults. Adult burns patients at The Alfred spent 48.7 hours in theatre in the first 72 hours. There were a further 390 bushfire-related ED presentations across the state in the first 72 hours. Most patients with serious burns were triaged to and managed at burns referral centres. Throughout the disaster, burns referral centres continued to have substantial surge capacity.

Conclusions: Most bushfire victims either died, or survived with minor injuries. As a result of good prehospital triage and planning, the small number of patients with serious burns did not overload the acute health care system.