We previously reported persistently high rates of cannabis use in three Indigenous communities in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory; in our longitudinal studies,1-3 72% of males and 23% of females aged 13–36 years were current users at baseline (2001).2 We also found that the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and cannabis dependence increased with more frequent cannabis use, and we documented a heavy burden on community finances and health services.2,4

These reports informed changes in policies that featured policing strategies targeted at cannabis supply and associated problems in remote NT communities generally.5 However, the Indigenous communities we studied were not engaged in or aware of these wider strategic shifts. Indigenous researchers became alarmed at respondents’ reports of cannabis-related harms during interviews in 2005–2006 and expressed a desire to disseminate the research findings and describe their insights to the respondents, their families and the wider community. They envisaged that, through such a feedback process, their communities would become better informed about cannabis use and its consequences, and so would be able to make more informed choices about cannabis. Here, we report the approach we developed to providing feedback on research, the processes involved, and the implications.

There is widespread endorsement for disseminating research results back to study communities,6,7 and for the importance of correcting power imbalances in research involving vulnerable populations such as Indigenous Australians.8 In the past 30 years, approaches to conveying research results to the Indigenous groups studied have progressed from no feedback (pre-1970s) to findings being used as an impetus for change (mid 1990s).9 Diverse methods for doing this have been described for a wide range of audiences.6,10 However, few studies provide specific practical guidelines, especially where language and cultural differences compound the difficulties faced. One NT study used locally understood concepts of “land, body and spirit” to disseminate adult mortality data.11 Another survey, of Aboriginal health workers in the NT and South Australia, identified preferences for pictorial representations of survey information.12 Pictorial representations of program outcomes were also used to convey findings about infant birthweight in three Aboriginal communities in the NT.13 However, there is a lack of detailed examination of the processes used to communicate epidemiological data in remote Indigenous Australia.

The three study communities in Arnhem Land have been described in detail elsewhere.2 A single Indigenous language is spoken in these communities, and cultural concepts are generally intact. English is a second language; English language skills vary greatly, as does literacy in younger people.14 Our continuing studies of cannabis use3 are collaborative efforts between non-Indigenous and local Indigenous researchers. Commitment by Indigenous researchers to address cannabis-related harms in their communities since the late 1990s has been pivotal to achieving these research outcomes.

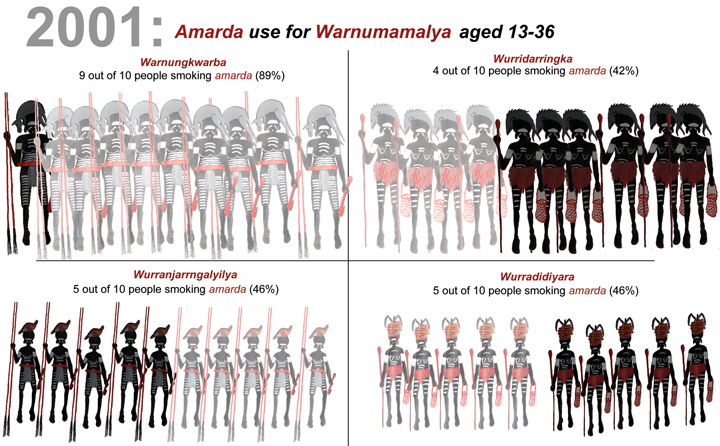

To represent the age groups of the population sample, the Indigenous researchers chose to use locally recognised descriptors of the life stages for males and females. These descriptors are not fixed according to calendar age, and the definition of each may vary from one individual to another depending on cultural considerations and individual characteristics. A local Indigenous artist was commissioned to draw relevant images. The Indigenous researchers chose to depict cannabis users as faded figures, as they considered users to be weakened by their drug use (Box 1).

Dissemination of the resources began in May 2007. Initial responses to the materials were gauged from semistructured interviews with 30 Indigenous and eight non-Indigenous participants, interviewed either individually or in groups. The main questions were about attitudes towards the materials and their appropriateness for local Indigenous people. Interviews of 15–60 minutes were conducted opportunistically across the three study communities with community members, health centre personnel, linguists, representatives of governing Indigenous organisations, police, and staff of correctional services, the aged care service and schools. Interviews with Indigenous participants were conducted by M J J and K S K L, using plain English and the local language. Most participants commented positively about the locally drawn pictures used to describe prevalence of cannabis use. Many also remarked about the importance of providing communities with this kind of information using “our ways of describing things”. Negative comments were few. Suggestions for improvements were offered, such as adding more local language words to describe cannabis use, and more clearly differentiating between the local language and English (Box 2).

Rather than providing literal translations, our efforts focused on identifying common concepts, to widen the community understanding of our studies of cannabis use. Early indications are that comprehension of the research findings was considerably enhanced among Indigenous researchers and community members. The approach also appears to be flexible enough to convey information effectively to people of different ages and with different levels of English comprehension and reading ability — a positive first step in improving community-wide literacy about frequent cannabis use and related harms, including mental health impacts.15 As explained by one community leader:

It makes good sense . . . with our pictures and words everyone can understand this one, even the young ones. For the first time we can see how many people are using gunja and how gunja is affecting our communities.

Indigenous researchers’ capacity was strengthened. They took on the challenging task of seeking community review of the feedback resources and disseminating the resources to all study communities and local service providers. They were delegated by community leaders to present their work at a national drug and alcohol conference.16 Their enhanced understanding of prevalence of cannabis use and its consequences in their communities enabled them to secure funding for a project to assist a closely affiliated community that was also experiencing high levels of cannabis use.

Already families have come to see me asking questions about the poster and book. We are being shown information from research about our communities that has never been given back to us in this way, using our ways of looking at the world. Now we can start to tell our people about how many people get chained to that gunja and about the sickness and worry from using too much, so they have this knowledge. (M J J)

Building community understanding and momentum for change through a community-feedback process is important for research and health promotion efforts, whether these are in a remote Indigenous community or an urban multicultural setting. We have shown that it is possible to convey health information using this simple and strategically important approach. Some key factors made this possible. Sound relationships between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, the study communities and the service providers created a basis of trust on which to conduct the research. The role of the Indigenous researchers was pivotal. Their participation combined pragmatic, moral, interventionist and epistemological rationales for involving Indigenous people in research, consistent with best practice.17 Their capacity for comprehensive community liaison, considered guidance and willingness to share their ways of understanding the research stimulated participation from other community members. They also continually challenged the non-Indigenous researchers to seek their own insights and to consider alternative approaches that would enable their own communities to better understand the research conducted in these disadvantaged and vulnerable groups.

1 Presentation of prevalence estimates of cannabis use among 262 people aged 13–36 years at baseline (2001)

|

2 Comments about the resources (book and DVD) from community members and local service providers*

Pictures work well; I can see how much gunja [cannabis] people in our communities use.

The faded ones are the ones that use that gunja; the darker ones have a healthy lifestyle.

Works well with the four groups to show who we talked to (men, women, boys and girls).

We all sat there as a family listening to the DVD.

A good resource to show students.

Make a poster about gunja and [depression].

Use a different word for “some” [in describing the levels of cannabis use].

Italicise the local language words. (Non-Indigenous participant)

Make the book [A4 size] a little smaller [A5 size] so it is easier to carry around and show people.

* Participants comprised 30 Indigenous and eight non-Indigenous people.

- K S Kylie Lee2

- Muriel J Jaragba3

- Alan R Clough1,4

- Katherine M Conigrave5,2

- 1 School of Public Health, Tropical Medicine and Rehabilitation Sciences, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD.

- 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

- 3 Aboriginal Mental Health Program, Top End Division of General Practice, Darwin, NT.

- 4 School of Indigenous Studies, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD.

- 5 Drug Health Service, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

We thank the Indigenous researchers, study communities, respondents, health clinics, linguists, land council, community councils, police and other service providers who were involved but remain anonymous. The resources feature original artwork by Kirk Watt. The assistance of Jenni Langrell from the NT Health Department and Mira Branezac from the NSW Health Drug and Alcohol Health Services Library is appreciated. The project was funded by the NHMRC National Illicit Drug Strategy (Grant No. NIDS 042) and the Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation Foundation. Kylie Lee was supported by an NHMRC Training Scholarship for Indigenous Australian Health Research.

None identified.

- 1. Clough AR, Cairney SJ, Maruff P, Parker RM. Rising cannabis use in Indigenous communities [letter]. Med J Aust 2002; 177: 395-396. <MJA full text>

- 2. Clough AR, d’Abbs P, Cairney S, et al. Emerging patterns of cannabis and other substance use in Aboriginal communities in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory: a study of two communities. Drug Alcohol Rev 2004; 23: 381-390.

- 3. Clough AR, Lee KSK, Cairney S, et al. Changes in cannabis use and its consequences over three years in a remote Indigenous population in Northern Australia. Addiction 2006; 101: 696-705.

- 4. Clough AR, D’Abbs P, Cairney S, et al. Adverse mental health effects of cannabis use in two Indigenous communities in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia: exploratory study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005; 39: 612-620.

- 5. Delahunty B, Putt J. The policing implications of cannabis, amphetamine and other illicit drug use in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and Australian Institute of Criminology, 2006. http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/other/2006-ndlerfmono15.html (accessed Oct 2007).

- 6. National Health and Medical Research Council. Keeping research on track: a guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about health research ethics. Canberra: NHMRC, 2005. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/e65syn.htm (accessed Oct 2007).

- 7. Mathews J. The communication/dissemination of research findings. In: Duquemin A, d’Abbs P, Chalmers E, editors. Making research into Aboriginal substance misuse issues more effective. Working Paper No. 4. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, 1993.

- 8. Eades SJ, Read AW, Bibbulung Gnarneep Team. The Bibbulung Gnarneep Project: practical implementation of guidelines in Indigenous health research. Med J Aust 1999; 170: 433-436.

- 9. Brown J, Hunter EM, Whiteside M. Talking back: the changing nature of Indigenous health research feedback. Health Promot J Austr 2002; 13: 34-39.

- 10. Hunter EM. Feedback: towards the effective and responsible dissemination of Aboriginal health research findings. Aborig Health Inf Bull 1992; 17: 17-21.

- 11. Weeramanthri T, Plummer C. Land, body and spirit, talking about adult mortality in an Aboriginal community. Aust J Public Health 1994; 18: 197-200.

- 12. Djoymi T, Plummer C, May J, Barnes A. Aboriginal health workers and health information in rural Northern Territory. Darwin: NT Department of Health and Community Services, 1993.

- 13. Mackerras D. Birth weight changes in the pilot phase of the Strong Women Strong Babies Strong Culture Program in the Northern Territory. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 34-40.

- 14. Lee KSK, Conigrave KM, Clough AR, et al. Evaluation of a community driven preventive youth initiative in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev 2007. In press.

- 15. Jorm AF, Lubman DL. Promoting community awareness of the link between illicit drugs and mental disorders [editorial]. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 5-6. <MJA full text>

- 16. Lee KSK, Jaragba M, Numamurdirdi H. Community feedback about our research findings: amarda use in three communities in Arnhem land. Presentation at the Australasian Professional Society on Alcohol and other Drugs Annual Scientific Conference; 2006 Nov 6–8; Cairns, QLD.

- 17. Kowal E, Anderson I, Bailie R. Moving beyond good intentions: Indigenous participation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health research. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005; 29: 468-470.

Abstract

Our aim was to disseminate research results about the very high rates of cannabis use in three remote Aboriginal communities in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, to the study populations.

To achieve this we translated prevalence estimates, using local concepts of life stages, numbers and quantities.

The reaction of the local community to results presented in this way was characterised by the phrase used when understanding something for the first time: Wa! Ningeningma arakba akina da! (“Oh! Now I know, that’s it!”).

To successfully disseminate research findings in these communities, it is critical to undertake comprehensive community liaison, to find common conceptual understandings and to build the skills of local Indigenous researchers.