Once upon a time, there was a buzz of excitement and talk that echoed through the streets and homes of Darwin. This frenzied movement of people indicated that the fish trap hunters had returned! Bush telegraph was alive and well during those times. As a result, a gathering would culminate at a well known residence and then the bartering, haggling, and negotiations would begin! The reason: fresh fish, crabs, the odd prawns and other marine edibles were on sale. The women mainly controlled this part, for they were the bargain hunters and could square a deal even with the sweetest-talking miser. Women played a significant role in the fish trap business. This was the life of good old Darwin. It was the time when fish traps were operated by local people, for local people, and when money was scarce. Money is still scarce today, but the fish traps are no longer. The government told us “they are illegal”. “They are an eyesore”, “hazardous to other fishing craft”, and “impact on the crab and barramundi industry” were other comments made in opposition to the fish trap. We asked ourselves, is it because “they” have determined that fish traps impact on “their” business?

Fisheries Act 1988 (NT)1

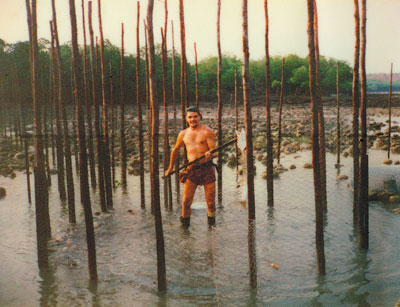

Geoffrey Angeles bags a barracuda. Gumboots protect against stonefish, stingrays, crabs, blue-ringed octopus, box jellyfish and other “nasties” in our tropical waters.

Fish, crabs, prawns, a variety of shellfish and other inland bush tucker were being consumed on a regular basis. Without realising it at the time, we had a rather healthy lifestyle. Routinely clearing the trap, along with some maintenance, ensured a regular exercise regime, plus some of these foods consumed had medicinal qualities.

Thus it is to this diet (traditional hunter-gatherer) and life style that we should turn when seeking explanations for (and solutions to) the characteristic pattern of chronic disease which emerges in all populations when they become more affluent economically and adopt a sedentary, westernized way of life.2

Today . . . unfortunately, and sadly, many of our people are suffering from an increase in a variety of chronic conditions ranging from cancers, diabetes, heart disease and stroke to other debilitating illnesses — associated with poor diet, reduced activities and exercise, and other unhealthy lifestyle habits.

More effort and a greater level of importance needs to be directed towards strategies in practical and inexpensive prevention. There is nothing wrong with some of the old and a little bit of the new. Reconciliation comes in many forms, but basically it is about bringing together, compromise, resolution and understanding. Shaking hands and saying sorry is surface stuff. Examples of partnerships that work are more real.

As a young boy growing up in Darwin, it was quite rare to see someone in a wheelchair. I remember an uncle having one leg, but he lost it as a serviceman in the war. He walked with his wooden leg and also played tricks on us as kids. Multiple amputations because of diabetes were virtually unheard of in the old days. Why was this? Could it be because of the diet back then, together with an abundance and sustainment of activities, such as sport, hunting, fishing and other regular recreational events?

Australian Aborigines develop a high frequency of type-2 diabetes when they make the transition from a traditional to an urban life-style.3

If we were to turn back the clock, or gather data from yesterday, the answer or solution to many of today’s chronic ailments may lie in waiting.

Donald (“Dookie”) Bonson using chicken-wire to make baskets to carry the fish. Fish trap in background.

- Geoffrey A Angeles1

- Menzies School of Health Research, Casuarina, NT.

- 1. Fisheries Act 1998 (NT), Pt V, Sec 53.

- 2. O’Dea K. Diabetes in Australian aborigines: impact of the western diet and life style. J Intern Med 1992; 232: 103-117.

- 3. O’Dea K, White NG, Sinclair AJ. An investigation of nutrition-related risk factors in an isolated Aboriginal community in northern Australia: advantages of a traditionally-orientated life-style. Med J Aust 1988; 148: 177-180.