Minor burns in children are extremely common. The Children's Hospital at Westmead (CHW) treats over 720 new cases each year. Over 500 of these are minor, the majority being scalds from tea and coffee.

It is well known that cooling a burn lessens pain and decreases burn depth, hence speeding healing times and decreasing the risk of scarring.1,2 Although recommendations vary, cold water (at a temperature of between 5°C and 25°C) has been proven to be the most effective method of cooling burn wounds.3 The temperature of running tap water in metropolitan Sydney varies between 12°C and 18°C (Sydney Water Board, personal communication), making it ideal for the first aid of burns.

Prolonged cooling, even at 18°C, may result in hypothermia, so it is recommended that the affected area be cooled for a minimum of 20 minutes, while keeping the rest of the patient warm.2,3 Iced water (< 4°C) deepens tissue injury as a result of vasoconstriction, and also increases the risk of hypothermia.1-3

Cooling is beneficial if started within three hours of injury, significantly reducing pain and oedema,1,4 so benefit can be gained by commencing cooling on arrival at a healthcare facility within that time. Immediate cooling leads to a reduction of the fluid required for resuscitation and a decrease in the fluid shift into unburnt tissues by turning off the cytokine response and release of histamine.5 This minimises metabolic acidosis.5 Histological and macroscopic comparison between biopsies from burns that have been cooled and those that have not show that cooled burns are less deep, have less final tissue necrosis and an earlier and more rapid rate of re-epithelialisation.1-3

There is no objective evidence as to the optimal duration of cooling. Studies have used periods ranging from 30 seconds to a few hours, measuring the rate of fall of skin temperature, severity of burn and the subsequent mortality rate in experimental animals.1,3 In discussions with experts, none are willing to be dogmatic, but recommend periods of at least 20 to 30 minutes.

We undertook this study to investigate the adequacy of first aid following minor burns.

Over the five months, 109 consecutive patients were entered into the study. Most burns (69; 63%) were scalds, 23 (21%) were contact burns, 12 (11%) were flame burns, and five (5%) were chemical or electrical burns.

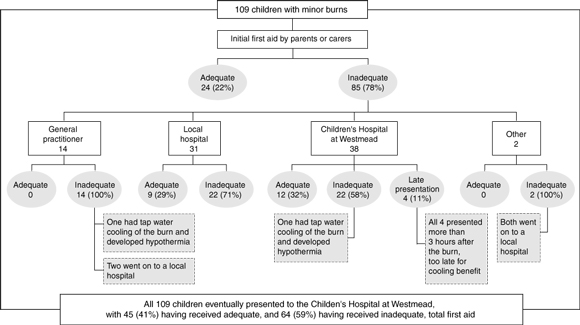

Only 24 of the 109 children (22%) received adequate initial treatment by parents or carers. Of the 85 who received inadequate initial first aid, 60 children (55%) did not receive adequate subsequent first aid, and four presented after more than three hours. As shown in Box 1, among the 85 who did not receive adequate initial first aid, subsequent treatment was also suboptimal in all 14 patients who contacted their general practitioners first, 22 of the 31 (71%) who contacted their local hospital first, 22 of the 38 (58%) who contacted CHW first, and both patients who contacted other health professionals (eg, pharmacy staff, ambulance personnel) first.

Nearly all children (92%) had some cold water applied initially. Fifty-one (47%) had a soaked dressing applied at some stage in their first aid, most often for transport to medical care, but only eight had the soaked dressing cooled again or changed. Transport to a medical facility was shown to interfere with cooling in 60 cases (55%). Cooling was only restarted in eight cases on arrival at the medical facility, even though it had been inadequate at the scene.

For 14 children who were receiving good first aid initially (13%), continuing to apply tap water was discouraged on the advice of a GP, pharmacy, medical centre or local hospital.

Five children (5%) had no water cooling at all, and nine (8%) had ice applied to their burns.

From our finding that cooling of the burn was initiated in so many children, it is clear that the benefits of cooling are well known in the community. Cooling was often stopped to get the child to medical treatment. It appears that a call for help or information in the treatment of burn wounds can actually negatively influence the care, such as in the cases of children in whom continuing to apply tap water was discouraged or the use of ice was encouraged. Soaked dressings were rarely changed. These warm very quickly and should be changed every few minutes to ensure the temperature of the burnt skin remains low.6 This can provide good short term analgesia until tap water cooling can be reinstituted.

Many burns are peripheral and easy to cool under running tap water while keeping the rest of the child warm to prevent hypothermia. Hypothermia can occur when the whole child is exposed to water, such as in a bath.

There is a lack of knowledge about first aid for treating burns at all levels of healthcare. Education is needed at all levels in the community. Our recommendations for first aid treatment of minor burns are summarised in Box 2.

1: First aid outcomes of 109 children with minor burns who presented to the Emergency Department or Acute Wound Clinic, the Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, during the five-month study period

2: Recommended first aid treatment of minor burns

Run cold tap water directly onto the burn for at least 20 minutes (use may be limited by difficulties in preventing hypothermia).

Keep the rest of the patient warm; increase the ambient temperature to 25°C–30°C, remove wet clothing, cover unburnt areas (eg, with a blanket).

Continue cooling throughout transport (fine mist spray or frequently changed soaked dressings).

Never use ice.

Note that starting first aid within three hours after a burn is beneficial.

- 1. Davies JWL. Prompt cooling of burned areas: a review of the benefits and the effector mechanisms. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1982; 9: 1-6.

- 2. Lawrence JC. British Burn Association recommended first aid for burns and scalds. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1987; 13: 153.

- 3. Sawada Y, Urushidate S, Yotsuyanagi T, Ishita K. Is prolonged and excessive cooling of a scalded wound effective? Burns 1997; 23: 55-58.

- 4. Raine TJ, Heggers JR, Robson M, et al. Cooling the burned wound to maintain microcirculation. J Trauma 1981; 21: 394-397.

- 5. Ofeigsson OJ. Water cooling. First aid treatment for scalds and burns. In: Davies JWL. Prompt cooling of burned areas: a review of the benefits and the effector mechanisms. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1982; 9: 1-6.

- 6. St John Ambulance Australia website. http://firstaid.commslab.gov.au/stjohn/stjnat/txtspace/qr4.htm (no longer available; link http://www.stjohn.org.au/ added Nov 2005)

Abstract

Objective: To identify the adequacy of first aid care following minor burns in children.

Design: Prospective case series.

Setting: Emergency Department and Acute Wound Clinic, the Children's Hospital at Westmead (CHW), Sydney.

Participants: 109 children who presented with minor burns (10% body surface area or less) to CHW over the five months from 2 November 1998 to 23 March 1999.

Main outcome measures: Comparison of the adequacy of first aid delivered by parents and carers, general practitioners, local hospitals, and CHW.

Results: Burns included scalds, contact, flame, chemical or electrical burns. Adequate initial first aid had been given by parents or carers in only 24 of 109 cases (22%). The 85 children who presented to medical care after inadequate initial first aid was given by parents or carers included 14 of 14 (100%) who had presented to their general practitioner (GP), 22 of 31 (71%) who had presented to their local hospital, 22 of 38 (58%) who had presented to CHW, and 2 of 2 (100%) who had had first contact with other health professionals.

Conclusions: This study shows that there is a need to educate parents and health professionals regarding appropriate first aid for burns.