It is essential that clinicians know the law to shape its evolution

In Australia, and across the world, an estimated 2–3% of young people identify as transgender and/or gender diverse (trans),1 with a gender identity that is not congruent with their sex assigned at birth. Trans children and adolescents face discrimination, bullying and social exclusion,2 and have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities, self‐harm and suicide attempts relative to the general Australian population.3 Many trans children and adolescents have gender dysphoria, which is significant distress or functional impairment associated with incongruence between their internal sense of gender and the sex assigned to them at birth.4

Over the past decade, there has been a proliferation in the number of trans young people presenting with gender dysphoria.5 In response, services have been established across Australia, with multidisciplinary specialised gender identity clinics in major cities and, increasingly, general practitioners in geographically isolated locations offering access to care.2 Medical treatment for gender dysphoria typically occurs in three stages beginning in early puberty: stage 1, puberty suppression with puberty blockers; stage 2, gender‐affirming treatment with gender‐affirming hormones; and stage 3, surgical gender‐affirming treatment with surgical interventions. Throughout this process, psychological support for the young people and counselling for parents is essential.6,7

The legal frameworks governing consent for the treatment of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents have rapidly evolved alongside medical advances. This article provides an update of current laws and contextualises this with reference to historical developments in this dynamic space. Ongoing tensions both within, and between, clinical and legal practice are highlighted.

Current laws guiding consent in the treatment of gender dysphoria

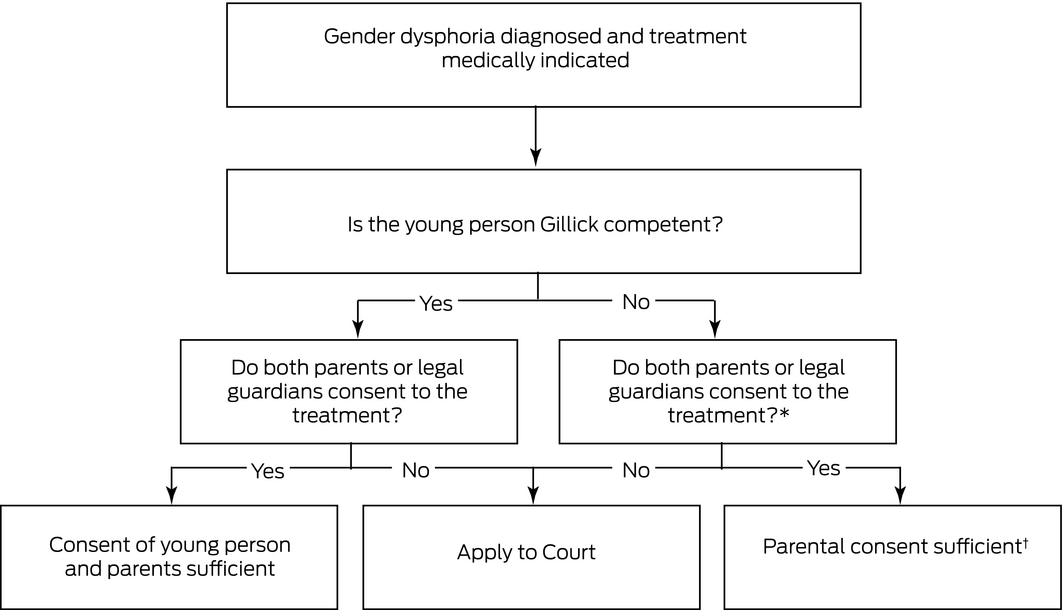

The laws governing consent for the treatment of gender dysphoria are distinct from that for routine medical procedures, where a child who is Gillick competent may consent to their own treatment, or special medical procedures, where court authorisation is required in all cases (online Supporting Information). Currently, all three stages of treatment for gender dysphoria in children and adolescents require consent from all parties with parental responsibility. This applies even when a young person is Gillick competent and consents to their own treatment. If there is any dispute between treating medical practitioners or parents regarding a young person’s Gillick competence and/or diagnosis or treatment, a court application is required.8 Box 1 illustrates this with an algorithm for practitioners to determine the appropriate pathway to obtain consent when treatment is indicated for a minor (generally persons under 18 years old; online Supporting Information) who has been diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

Once an application is made, the court will make a finding about the young person’s Gillick competence in all cases.8 Where the dispute is only regarding an adolescent’s Gillick competence, the Court will make an order or declaration under general powers conferred by s 34(1) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (the Act).11 If the adolescent is declared a mature minor and there is no other dispute, they may determine their own treatment without court authorisation. However, if the young person does not have capacity or there is dispute about the diagnosis or treatment, the court will proceed to consider whether treatment should be authorised, having regard to the young person’s best interests under its welfare jurisdiction (s 67ZC).8,11 In making this assessment, courts give significant weight to the views of the child in accordance with their age or maturity.12

Key developments in legal consent for gender dysphoria treatment

To understand how consent for gender dysphoria treatment developed as a distinct category for consideration, it is necessary to appreciate the history of its evolution through case law in parallel with advances in medical science and practices. Box 2 provides an overview of landmark cases since the first application to the Family Court of Australia (FCoA) with Re Alex: hormonal treatment for gender identity dysphoria in 2004.13 Almost a decade later, the Full Court of the Family Court of Australia (Full Court) in Re Jamie (2013) noted that gender dysphoria was no longer a novel or unusual condition [99] and stage 1 and 2 treatment would now be regarded as therapeutic treatment rather than special medical procedures that required court authorisation in all cases.12 However, stage 2 treatment, bearing risks of grave and irreversible consequences, warranted court involvement for the assessment of a young person’s capacity to consent in all cases. Where a child was found to lack capacity to consent, court authorisation for treatment would be necessary. The clinical and legal landscape to this point has previously been detailed.17 Since then, two landmark cases have transformed the conceptualisation of consent in this space: Re Kelvin (2017) and Re Imogen.

In Re Kelvin (2017), the Full Court revisited the issue of stage 2 treatment. The majority cited international treatment guidelines from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)7 and the Endocrine Society18 and statements regarding the upcoming first Australian‐specific guidelines (unpublished)14 in support of its conclusion that judicial understanding of gender dysphoria and its treatment had fallen behind the advances in medical science since Re Jamie. Where assessment, diagnosis and treatment are administered in accordance with best practice guidelines, the risks and consequences of treatment, while “at least in some respects irreversible” no longer outweigh its therapeutic benefits [162].14 An application to court to determine a young person’s Gillick competence was no longer required in all cases. In considering the broader context of the case, the Full Court expressed concerns with “incomplete, and, at worst, inaccurate” media reporting of legal issues, and emphasised that decisions are made within “the confines of the questions stated”; specifically in this case, where there is no dispute between parents or between the parents and treating medical practitioners [115‐116].14 Stage 3 treatment has followed a similar trajectory, with Re Matthew (2018)16 and Re Ryan (2019)19 extending the principles of stage 2 treatment in Re Kelvin (2017) to stage 3 treatment.

The issue of consent in cases of dispute was first considered in Re Imogen in 2020,8 where the FCoA noted that while the Full Court in Re Kelvin had departed from Re Jamie in some respects, important parts of that decision remained intact. Specifically, where there is dispute about any aspect of treatment, an application to the court remains mandatory. In accordance with the Attorney‐General of the Commonwealth’s statement, the FCoA reasoned that proper medical practice requires court involvement, without which, a practitioner shoulders heightened risks of civil or criminal liability for assessing a child as Gillick competent when they may not be, or incorrectly giving preference to one parent over another. In other words, the burden of responsibility for deciding disputes falls on the courts, not medical practitioners.

This enquiry into the need for parental agreement extended into considerations of requirements for parental consent. Shortly after Re Kelvin, the Australian Standards of Care and Treatment Guidelines for Trans and Gender Diverse Children and Adolescents (the Guidelines) was published, reflecting the medical profession’s understanding that where an adolescent was considered competent to provide informed consent for stage 2 treatment, parental consent was ideal but not necessary.20 However, in Re Imogen, the Honourable Justice Watts noted that this was an “incorrect” statement of the current law [27]8 and clarified:

“… any treating medical practitioner seeing an adolescent under the age of 18 is not at liberty to initiate stage 1, 2 or 3 treatment without first ascertaining whether or not a child’s parents or legal guardians consent to the proposed treatment. Absent any dispute by the child, the parents and the medical practitioner, it is a matter of the medical professional bodies to regulate what standards should apply to medical treatment. If there is a dispute about consent or treatment, a doctor should not administer stage 1, 2 or 3 treatment without court authorisation [63].”8

The Guidelines have since been updated to reflect the above.6

Practical implications

On a practical level, Re Kelvin shifted the responsibility for authorising stage 2 treatment from the Court onto clinicians, some of whom experienced greater pressure from children and families to provide treatment.21 Following Re Imogen, the right to decide treatment is more widely dispersed among clinicians, the court, the young person, and their families. Conversely, there are concerns that the requirement for positive parental consent from both parents places a significant administrative burden on medical practitioners to seek consent from parents and support patients through litigation processes that may also result in treatment delays for many patients.22 While Courts have yet to make a declaration that departs from the wishes of a Gillick competent child seeking treatment for gender dysphoria, requiring mature minors to obtain positive parental consent undermines the very principle of Gillick competence. This has been criticised as a paternalistic intrusion into a young person’s right to self‐determination.22,23

Conclusion

The laws governing treatment consent in gender dysphoria have rapidly evolved in the past two decades, with a demonstrated history of doing so in parallel with medical advances. In recent times, the uncertainty, and at times confusion, regarding the law has resulted in volatility in clinical practice.22 It is essential that all clinicians know the law, not only to abide by it but also to effectively advocate for patients within current frameworks and, in doing so, shape its evolution for optimal clinical outcomes.

Box 1 – Algorithm for determining the consent procedure for the treatment of young persons diagnosed with gender dysphoria as per Re Imogen (2020)

*While non‐binding on the Family Court of Australia, in the case of Re A (2020), the Supreme Court of Queensland exercised parens patriae jurisdiction and held that where one parent is estranged and not disputing, but not consenting to stage 1 treatment, consent from the other parent is sufficient.9 † See also Re Chloe (2018), which held that persons with parental responsibility, in that case a Minister, of a child under state government care may provide consent.10

Box 2 – Evolution of legal frameworks governing consent to treatment of gender dysphoria for minors

|

Landmark cases |

Precedent established |

Application to court required in all cases? |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Absent dispute: stages 1 and 2 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Re Alex (2004) FamCA13 |

Stage 1 and 2 treatment novel, non‐therapeutic and a special medical procedure |

Yes — for treatment authorisation |

|||||||||||||

|

Re Jamie (2013) FamCAFC12 |

Stage 1 therapeutic and reversible |

No* |

|||||||||||||

|

Stage 2 therapeutic but with risks of grave and irreversible consequences |

Yes — for assessment of child’s Gillick competence and, if found not to have the capacity to consent, for treatment authorisation* |

||||||||||||||

|

Re Kelvin (2017) FamCAFC14 |

Stage 1 and 2 treatment therapeutic |

No |

|||||||||||||

|

Absent dispute: stage 3† |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Re LG (2017) FCWA15 |

Principles applied to stage 2 treatment in Re Jamie extended to stage 3 treatment |

Yes — as per Re Jamie |

|||||||||||||

|

Re Matthew (2018) FamCA16 |

Principles applied to stage 2 treatment in Re Kelvin extended to stage 3 treatment |

No — as per Re Kelvin |

|||||||||||||

|

In cases of dispute: Stages 1, 2 and 3† |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Re Imogen (2020) FamCA8 |

Medical practitioners must seek consent for the proposed treatment from a child’s parents or legal guardians [63]. This applies even where a young person is Gillick competent [44–59] |

No — as per Re Jamie |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* A child who is Gillick competent can consent to stage 1 or 2 treatment, absent any controversy. If there is any dispute between the parents, child and treating medical practitioners, Court authorisation is required. In making a determination of what is in the child’s best interests, the Court should give significant weight to the child’s view in accordance with their age or maturity: Bryant CJ at [140](b); Finn J at [172] and Strickland J at [192]. † These cases were decided by single judges and provide guidance; they are not binding on the Full Court of the Family Court (generally comprising of three to five judges). |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Strauss P, Lin A, Winter S, et al. Options and realities for trans and gender diverse young people receiving care in Australia’s mental health system: findings from Trans Pathways. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2021; 55: 391–399.

- 2. Telfer MM, Tollit MA, Pace CC, Pang KC. Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for transgender and gender diverse children and adolescents. Med J Aust 2018; 209: 132–136. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/209/3/australian‐standards‐care‐and‐treatment‐guidelines‐transgender‐and‐gender

- 3. Strauss P, Cook A, Winter S, et al. Associations between negative life experiences and the mental health of trans and gender diverse young people in Australia: findings from trans pathways. Psychol Med 2020; 50: 808–817.

- 4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013.

- 5. Zucker KJ. Adolescents with gender dysphoria: Reflections on some contemporary clinical and research issues. Arch Sex Behav 2019; 48: 1983–1992.

- 6. Telfer MM, Tollit MA, Pace CC, Pang KC. Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for trans and gender diverse children and adolescents, version 1.3. Melbourne: Royal Children’s Hospital; 2020. https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/adolescent‐medicine/australian‐standards‐of‐care‐and‐treatment‐guidelines‐for‐trans‐and‐gender‐diverse‐children‐and‐adolescents.pdf (viewed Nov 2021).

- 7. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender‐nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend 2012; 13: 165–232.

- 8. Re Imogen (No 6) [2020] FamCA 761.

- 9. Re a declaration regarding medical treatment for “A” [2020] QSC 389.

- 10. Re Chloe [2018] FamCa 1006.

- 11. Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

- 12. Re Jamie [2013] FamCAFC 110.

- 13. Re Alex: hormonal treatment for gender identity dysphoria [2004] FamCA 297.

- 14. Re Kelvin [2017] FamCAFC 258.

- 15. Re LG [2017] FCWA 179.

- 16. Re Matthew [2018] FamCA 161.

- 17. Smith MK, Mathews B. Treatment for gender dysphoria in children: the new legal, ethical and clinical landscape. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 102–104. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/2/treatment‐gender‐dysphoria‐children‐new‐legal‐ethical‐and‐clinical‐landscape

- 18. Hembree WC, Cohen‐Kettenis P, Delemarre‐Van HA, et al; Endocrine Society. Endocrine treatment of transexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 3132–3154.

- 19. Re Ryan [2019] FamCA 112.

- 20. Telfer MM, Tollit MA, Pace CC, Pang KC. Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for trans and gender diverse children and adolescents, version 1.1. Melbourne: Royal Children’s Hospital; 2018. https://www.shil.nsw.gov.au/NSWSexualHealthInfolink/media/SiteContent/Files/5‐Australian‐Standards‐of‐Care_TGD‐children‐and‐adolescents.pdf (viewed Nov 2021).

- 21. Kozlowska K, McClure G, Chudleigh C, et al. Australian children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: Clinical presentations and challenges experienced by a multidisciplinary team and gender service. Hum Syst 2021; 1: 70–95.

- 22. Jowett S, Kelly F. Re Imogen: a step in the wrong direction. Aust J Fam Law 2021; 34: 31–56.

- 23. Young L. Mature minors and parenting disputes in Australia: engaging with the debate on best interests v autonomy. UNSWLJ 2019; 42: 1362–1385.

No relevant disclosures.