The international shortage of piperacillin/tazobactam (PT) in 2017 prompted its replacement by intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanate (IVAC).1 Two studies have examined the effect of broad spectrum antibiotic usage on the epidemiology of vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus (VRE) in hospitals. An interrupted time series study found that VRE prevalence declined after partial replacement of cephalosporins, vancomycin and clindamycin by ampicillin/sulbactam and, to a lesser extent, PT.2 In another study, a switch from ceftazidime to PT for febrile neutropenia was associated with reduced VRE acquisition in a haematology unit.3

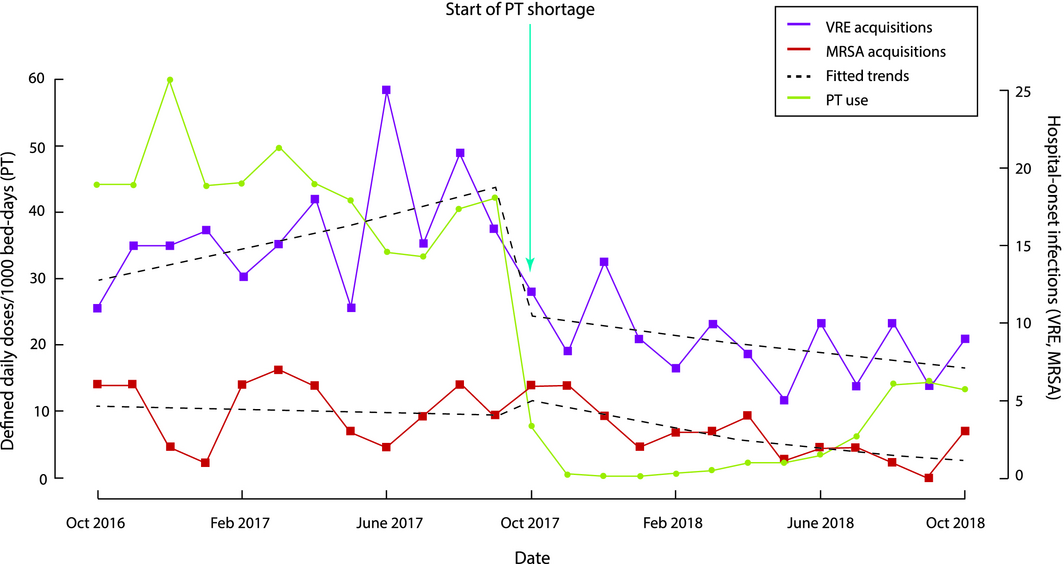

We examined the impact of the PT shortage on VRE and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) acquisitions at the John Hunter Hospital (Newcastle), where there has been a sustained outbreak of VRE since 2014.4 We compared the incidence of hospital‐onset acquisitions (hospital‐wide) during the 12 months before (Oct 2016 – Sept 2017) and 12 months after (Nov 2017 – Oct 2018) the start of the PT shortage. We analysed routine surveillance data; the first unique patient VRE and MRSA isolates from blood, tissue or fluid specimens were deemed indicators of morbidity. The interrupted time series was analysed in a regression framework with a generalised linear model; changes in usage trends and levels, adjusted for seasonality, were assessed. Structural breaks in the series were explored with a blinded generalised fluctuation test.

Ethics approval was not required; we observed the guidance of the Outbreak Reports and Intervention studies of Nosocomial infection (ORION) statement.5

Twelve‐month mean PT use declined from 44 defined daily doses (DDD)/1000 occupied bed‐days (OBD) before the shortage to 5 DDD/1000 OBD; IVAC usage increased from 4 to 33 DDD/1000 OBD. As IVAC is a narrower spectrum antibiotic, total broad spectrum parenteral antimicrobial use fell from 129 DDD/1000 OBD before the shortage to 91 DDD/1000 OBD.

A model with cyclical terms and a monthly lag effect best fitted the VRE acquisition time series, with a statistically significant change in level (P = 0.004) and trend (P = 0.002) at October 2017. A model with cyclical terms best fitted the MRSA time series, with a non‐significant reduction in MRSA events (10% per month) during the shortage (Box). There were no meaningful structural breaks in either time series.

There were 191 acquisitions of VRE and 53 of MRSA before the shortage; during the shortage, there were 101 (fall of 47%) and 31 (42% fewer) respectively. There were 24 sterile site detections of VRE and 49 of MRSA before the shortage, and eight (67% fewer) and 37 (24% fewer) during the shortage. Fifty‐three health care‐associated Clostridium difficile infections were detected before the shortage, 52 in the subsequent 12 months.

VRE and MRSA acquisitions and infections fell during the period of reduced PT use, although only the former was statistically significant. Replacement with broad spectrum agents was largely avoided. The introduction of a new cleaning wipe in February 2018 was the only significant change in practice at the hospital during the study period, during which hand hygiene compliance exceeded 90%. Exposure to PT or cefepime in intensive care has been associated with similar risks of VRE acquisition;6 investigations of the impact of IVAC on the risk of acquiring VRE or MRSA have not been published.

National Antimicrobial Utilisation Surveillance Program7 data for Australian tertiary hospitals documented an overall fall in PT use, from 60 to 41 DDD/1000 OBDs, during the shortage; mean broad spectrum use remained unchanged, as PT was replaced by ceftriaxone, cefepime and meropenem. In our experience, these agents are often used empirically in situations in which narrower spectrum agents could be safely employed, including intra‐abdominal infections for which prompt source control has been achieved, skin or soft tissue infections dominated by Gram‐positive bacteria, and pneumonia in patients at low risk of Gram‐negative infections.

We found that reducing broad spectrum antibiotic use was associated with reduced VRE transmission and infection. PT has now been re‐introduced on a restricted basis and usage remains at a much lower level than before the shortage. We will continue to observe trends in incidence and will also undertake a case–control study of VRE acquisitions. Reducing broad spectrum antibiotic use should be a primary goal for hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Received 26 April 2024, accepted 26 April 2024

- 1. Ferguson JK. Piperacillin+tazobactam shortage; recommended alternatives: HNELHD. AIMED: Let's talk about antibiotics. 9 June 2017. https://aimed.net.au/2017/06/09/piperacillintazobactam-shortage-recommended-alternatives-hnelhd (viewed Jan 2019).

- 2. Quale J, Landman D, Saurina G, et al. Manipulation of a hospital antimicrobial formulary to control an outbreak of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23: 1020–1025.

- 3. Bradley SJ, Wilson AL, Allen MC, et al. The control of hyperendemic glycopeptide‐resistant Enterococcus spp. on a haematology unit by changing antibiotic usage. J Antimicrob Chemother 1999; 43: 261–266.

- 4. van Hal SJ, Beukers AG, Timms VJ, et al. Relentless spread and adaptation of non‐typeable vanA vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium: a genome‐wide investigation. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 1487–1491.

- 5. Stone SP, Cooper BS, Kibbler CC, et al. The ORION statement: guidelines for transparent reporting of outbreak reports and intervention studies of nosocomial infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7: 282–288.

- 6. Paterson DL, Muto CA, Ndirangu M, et al. Acquisition of rectal colonization by vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus among intensive care unit patients treated with piperacillin‐tazobactam versus those receiving cefepime‐containing antibiotic regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 465–469.

- 7. SA Health. National Antimicrobial Utilisation Surveillance Program (NAUSP). Updated May 2019. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/clinical+programs/antimicrobial+stewardship/national+antimicrobial+utilisation+surveillance+program+nausp (viewed May 2019).

We thank Lorrae Gilbert (antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist) and Michelle Kennedy and Jeffrey Deane (infection control nurses responsible for multidrug‐resistant organisms and C. difficile surveillance) for their involvement in this study.

No relevant disclosures.