The known Health-related questions comprise the second most searched thematic area in Google, these topics providing 5% of the more than two trillion searches undertaken in 2016.

The new More than one-third of adult patients searched the internet for information on their problem before attending the emergency department; almost half regularly searched for such information, particularly younger and e-health literate patients. Searching had a positive impact on the doctor–patient interaction in most cases, and was unlikely to cause patients to question the diagnosis or advice of their treating doctor.

The implications It may be beneficial for doctors to acknowledge and discuss health-related internet searches with adult emergency department patients.

It has been reported that 43–56% of parents of children presenting to emergency departments (EDs) had searched online for health information at some time,1-3 and that 6–12% had undertaken a health-related search before taking their child to an ED.1-3 How such behaviour affects the doctor–patient relationship during an ED consultation is poorly understood.

In 1996, 1.6% of Australians had access to the internet at home;4 by 2015, this had increased to 86%,5 in addition to 21.3 million mobile devices used to download more than 90 000 terabytes of data in the final quarter of that year alone.6

Health is the second most frequently searched thematic area in Google, providing almost 5%7 of the worldwide total of more than two trillion searches in 2016.8 Health care providers can apply this information on a population level; for example, ED patient load has been predicted from the volume of website visits during the preceding night,9 and presentations to EDs with flu-like illness have been correlated with search engine metadata for the term “flu”.10

The influence of these searches on the doctor–patient relationship in the ED has not been investigated, but their effect has been studied in other contexts, especially general practice.11 General practitioners respond to internet-derived information described by patients in one of three ways: by reacting defensively and asserting their expert opinion; by collaborating with the patient to analyse the information; and by guiding the patient to reliable health information websites.12 It has been reported that general practice patients regard the internet as a supplementary resource that provides information supporting the doctor’s advice and enhancing their relationship,13 particularly patients who had the opportunity to discuss their online findings.14 However, internet searching can lead to conflict if the patient values internet-derived information above that of the doctor, causing them to ignore their advice.15,16

As the prevalence of health-related internet searching by adult ED patients and the influence of these searches on the doctor–patient relationship in the ED has not been examined in Australia, we aimed to determine the prevalence in this population of health-related internet searches, both in general and for the problem for which they had presented to the ED, and to determine the predictors and characteristics of their searches. We also examined the effect of patient health-related internet searches on the doctor–patient relationship and treatment compliance.

Methods

Design and setting

We undertook a cross-sectional study of adults presenting to the two large metropolitan tertiary centre EDs in Melbourne, at St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne and Austin Health, during 1 February – 31 May 2017. During 2016–17, the two EDs respectively received about 46 00017 and 84 00018 patients.

Participants

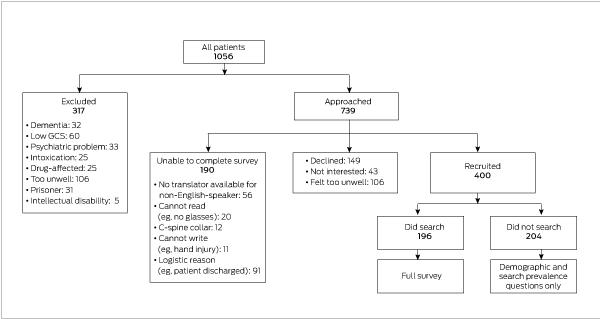

A representative sample of ED attenders was obtained during 60 recruitment shifts: 25 on weekdays (8 am – 6 pm), 25 during evenings (3 pm – 11 pm), and ten on weekends or overnight. Patients presenting to the ED during these shifts were included if they were over 18 years of age, but were excluded if they did not speak English, were prisoners, were unable to participate for medical reasons, or were cognitively impaired as assessed by the researcher (dementia, intellectual disability, psychiatric illness, intoxication, Glasgow coma scale score below 15 throughout emergency admission) (Box 1). Patients were screened for eligibility using triage notes and in person, and were approached for consent after their consultation with the treating clinician.

Data collection

Participants were advised that their responses would be anonymised. They completed a 51-item purpose-designed survey on paper or on an iPad (SurveyMonkey software). Demographic information collected included age, sex, income, education, first language, country of origin, and e-health literacy. Participants who indicated that they had searched for medical information regularly or for the current presentation also completed the Internet Search effect on Medical Interaction Index (ISMII) and compliance questions, as detailed below.

Measures

e-Health literacy was evaluated with the validated eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS).19 eHEALS has high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.88), item scale correlations (r = 0.51–0.76), and test–retest reliability (r = 0.49–0.68).19 Each of the eight items has five response options, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5); responses are summed to produce an overall score.

An extensive literature review found no measures of the effect of health-related internet searching on the doctor–patient relationship. An iterative process was therefore undertaken to develop a suitable measure. The result was the ISMII, a nine-item measure with Likert scale responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The ISMII includes seven positively worded questions (eg, “Information from the internet allows me to better understand my health provider”) and two reverse-scored negatively worded questions (eg, “Gathering internet health information makes me more anxious”). Each item was analysed individually, and the net effect of searching on the doctor–patient relationship was assessed with the total score. Scores above 27 indicate a positive influence on the relationship, scores below 27 a negative influence. The ISMII has not been formally validated but its face validity is supported by the iterative formation process and its acceptable internal consistency (see ).

The effect of internet searching on treatment compliance was measured with four purpose-designed, frequency-based Likert scale questions, developed with the same iterative process used to create the ISMII; response options ranged from never (1) to always (5).

Statistical analysis

We calculated that a sample size of 377 patients was required to accurately estimate prevalence with a precision of 5%, assuming an underlying prevalence of 50%.

Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM). Denominators for individual questions were adjusted for missing data (eg, item non-response).

Regression models were pre-specified to guard against spurious findings. The effect of each demographic variable on the outcome variable “searching for e-health information regarding the problem for which you presented to ED” was assessed in Pearson χ2 tests; if a significant association was found, the variable was included in the regression analysis. A binary multivariable logistic regression model (enter simultaneous method) that included age, sex, country of birth, highest level of education, and e-health literacy assessed the influence of these variables on the likelihood of searching the internet for health information. A multivariable linear regression model (enter simultaneous method) including the same variables (there were no significant associations with this outcome other than with e-health literacy and these demographic variables) assessed their influence on ISMII score.

The internal consistency of the e-HEALS and the ISMII question sets were assessed with the Cronbach α statistic; α ≥ 0.7 was deemed acceptable for analysing total scores.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committees (HREC) at Austin Health (reference, HREC/16/Austin/361). Governance approvals were obtained from the HRECs at Austin Health (reference, LNRSSA/16/Austin/378) and St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne (reference, LNRSSA/17/SVHM/15).

Results

Four hundred patients (St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, 220; Austin Health, 180) participated in the study (response rate, 73%). The mean age of participants was 47.1 years (standard deviation [SD], 21.1 years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 45.0–49.2 years); 51.8% were men. The mean eHEALS score for 371 respondents who completed this component was 28.2 (range, 8–40; standard deviation, 6.2; Cronbach α, 0.87). Further demographic data are included in Box 2.

Search behaviour characteristics

A total of 196 participants (49.0%; 95% CI, 44.1–53.9%) indicated that they regularly used the internet to search for health-related information; 139 (34.8%; 95% CI, 30.3–39.5%) reported searching for information on the problem for which they had presented to the ED.

In the univariate analysis, age (P < 0.001; Box 3), sex (P = 0.043), birth outside Australia (P = 0.024), highest level of education (P < 0.001), and e-health literacy (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with patients searching about the problem for which they presented to the ED, but only younger age (P = 0.004) and increasing e-health literacy (P < 0.001) were significantly predictive in the regression analysis. The likelihood of searching declined by 26% for each one step rise in age category (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60 or more years); for each one point rise in e-health literacy score, the likelihood of searching increased by 11% (Box 4).

The median number of searches by the 139 patients who searched regarding the problem for which they presented to the ED was three (interquartile range [IQR], 2–6); the median time spent searching was 20 minutes (IQR, 10–60 min). Searching was less prevalent closer in time to ED presentation; 86 searches (62%; 96% CI, 59–70%) were conducted more than 24 hours before presentation, compared with 12 searches (8.6%; 96% CI, 5.0–14%) while waiting in the ED (Box 5). Most searches were performed on smartphones (76%) and used the Google search engine (94%), primarily to search for information on symptoms (68%) or treatment (51%) (Box 5). The types and specific internet sites visited and trusted by patients are summarised in Box 6.

Search effect on the doctor–patient relationship

The mean ISMII score for the 196 participants who regularly searched the internet for health-related information was 30.3 (range, 7–41; 95% CI, 29.6–31.0; Cronbach α = 0.71). Searching had a net positive effect (total ISMII > 27) for 150 searchers (77.3%; 95% CI, 70.9–82.7%); a net negative effect (total ISMII < 27) was reported by 32 searchers (16%; 95% CI, 12–22%), while no effect (total ISMII = 27) was reported by 14 participants (7.1%).

Among the most notable findings for individual ISMII questions was that 132 of 195 participants (68.4%; 95% CI, 61.5–74.5%) agreed or strongly agreed that searching helped them communicate more effectively with health providers; 19 participants (9.8%; 95% CI, 6.4–15%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. A total of 155 respondents (79.5%; 95% CI, 73.7–84.9%) agreed or strongly agreed that searching helped them better understand their health provider during the consultation; 155 (80.7%; 95% CI, 74.6–85.7%) agreed or strongly agreed that searching allowed them to ask more informed questions, while six (3%; 95% CI, 1–7%) disagreed or strongly disagreed. However, 76 respondents (40%; 95% CI, 33–47%) agreed or strongly agreed that gathering information from the internet made them worried or anxious; 60 (31%; 95% CI, 26–38%) disagreed or strongly disagreed (Box 7).

A total of 153 respondents (78.9%; 95% CI, 72.6–84.0%) indicated that internet-derived health information never or rarely led them to doubt their diagnosis or treatment; 174 (91.1%; 95% CI, 86.2–94.3%) had never or rarely changed a treatment plan advised by a doctor because of online health information (Box 7).

Regression analysis of the ISMII total score by age, sex, country of birth, highest level of education, and e-health literacy indicated that only e-health literacy was a significant predictor (P < 0.001): for each one point increase in eHEALS score there was a 0.4 point increase in ISMII score (Box 8).

Discussion

We found that almost half of our sample of adult ED patients regularly searched the internet for health-related information, and more than one-third undertook a search regarding their presenting problem before attending the ED. Three earlier studies that examined search behaviour found that 24.5%20 and 45.8%11 of patients specifically searched for information on their current health problem before presentation, comparable with the 34.8% prevalence we found. The studies that found highest rates differed from ours methodologically; one, for example, excluded patients referred by general practitioners or delivered by ambulance.11

Some studies have identified that being female21 or younger22 is associated with a greater likelihood of seeking information from other health professionals, family, or online before presenting to an ED. However, other studies,20 like ours, have not found sex to a significant factor. We found that e-health literacy was a significant predictor of searching before presenting to an ED, indicating that those who are confident about internet-derived health information are more likely to seek it before they obtain professional assistance.

We found that searching the internet for information before presenting to an ED generally had a positive effect (from the patient’s perspective) on the doctor–patient interaction. Specifically, patients reported they were more able to ask informed questions, communicate effectively, and understand their health provider. This indicates that searching before attending an ED may have a positive effect by informing patients and improving communication between patients and health practitioners, consistent with earlier findings.11,13,14 In addition, it was shown that searching does not usually reduce the patient’s confidence in the diagnosis or treatment plan provided by the practitioner, nor is it associated with reduced compliance with these treatment plans. However, some patients reported that searching increased their anxiety, and this should be acknowledged by practitioners during the consultation.

Strengths of our study included the good response rate during recruitment from two large metropolitan public tertiary referral centres with differing demographic profiles. The age distribution of the sample was similar to that of all adult patients attending Victorian EDs.23 These strengths, in addition to the employment of the validated eHEALS tool, mean that our findings may be applicable to the broader Australian ED population.

Limitations

The participating EDs did not generally receive pregnant patients, and patients presenting with psychiatric problems were excluded for ethical reasons, although people with a history of psychiatric illness but presenting for a physical problem were included. The development and first use of the ISMII questionnaire, and its lack of formal validation and largely quantitative nature are further limitations.

Conclusion

More than one-third of adults presenting to two Melbourne EDs had searched the internet for information on the problem for which they had presented to the ED; nearly one-half had regularly sought health information on the internet, particularly younger and e-health literate patients. Searching for online health information had a positive impact on the doctor–patient relationship, particularly for patients with greater e-health literacy, and was unlikely to cause patients to doubt the diagnosis by a practitioner or to affect adherence to treatment. We therefore suggest that doctors acknowledge and be prepared to discuss with adult ED patients their online searches for health information.

Box 2 – Demographic data for the 400 adult emergency department patients recruited for the study

|

Characteristic |

Number (proportion) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|||||||||||||||

|

Men |

207 (52%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Women |

193 (48%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Education |

|||||||||||||||

|

Did not complete year 12 |

104 (27%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Completed year 12 |

70 (18%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Technical and further education |

38 (9.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Graduate certificate |

52 (13%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Bachelor degree |

85 (22%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Master’s or doctoral degree |

41 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

10 |

||||||||||||||

|

First language |

|||||||||||||||

|

English |

355 (90%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

41 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

4 |

||||||||||||||

|

Country of birth |

|||||||||||||||

|

Australia |

274 (71%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

110 (29%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

16 |

||||||||||||||

|

Household income |

|||||||||||||||

|

< $1500/week |

233 (64%) |

||||||||||||||

|

≥ $1500/week |

131 (36%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

36 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Prevalence of searching the internet for health-related information on the current emergency department presentation among 400 adult emergency department patients, by age

|

|

Number of searchers/number of participants |

Estimated proportion (95% CI) |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Age group (years) |

|

|

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

18–29 |

54/94 |

58% (47–67%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

30–39 |

31/75 |

41% (31–53%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

40–49 |

25/63 |

40% (28–52%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

50–59 |

13/50 |

26% (16–40%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

60 or more |

16/118 |

14% (8.5–20%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Binary logistic regression analysis: searching the internet for health-related information on the current emergency department presentation among 400 adult emergency department patients

|

Variable |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Age |

0.74 (0.61–0.91) |

0.004 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex |

0.65 (0.37–1.13) |

0.13 |

|||||||||||||

|

Country of birth |

0.72 (0.38–1.34) |

0.29 |

|||||||||||||

|

Highest level of education |

0.96 (0.81–1.15) |

0.66 |

|||||||||||||

|

eHEALS score |

1.11 (1.06–1.17) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Search characteristics of the 139 patients who searched regarding the problem for which they had presented to the emergency department

|

Variable |

Number |

Estimated proportion (95% CI) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Timing of search relative to emergency department presentation* |

|||||||||||||||

|

> 24 hours before presentation |

86 |

62% (59–70%) |

|||||||||||||

|

6–24 hours before presentation |

26 |

19% (13–26%) |

|||||||||||||

|

1–6 hours before presentation |

25 |

18% (12–25%) |

|||||||||||||

|

< 1 hour before presentation |

14 |

10% (6.1–16%) |

|||||||||||||

|

While waiting in the emergency department |

12 |

8.6% (5.0–14%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Search autonomy |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Search unassisted |

102 |

76% (68–82%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Search assisted by another person |

32 |

24% (17–32%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

4 |

— |

|||||||||||||

|

Search device* |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Smartphone |

105 |

76% (68–82%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Laptop computer |

60 |

43% (35–52%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Tablet/pad |

27 |

19% (14–27%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Desktop computer |

25 |

18 (12–25%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Search engine* |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

130 |

94% (88–97%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Bing |

2 |

1% (0.4–5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Yahoo |

2 |

0.7% (0.1–4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other responses |

1 |

3% (1–7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Did not use a search engine |

4 |

0.7% (0.1–4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Search term categories* |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Symptoms |

94 |

68% (60–75%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Treatments |

69 |

51% (42–58%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Diagnosis |

57 |

41% (33–49%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Choice of health centre |

32 |

23% (17–31%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Tests |

19 |

14% (8.9–20%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Medical specialties |

19 |

14% (8.9–20%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Search terms† |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Stomach/abdominal pain |

17 |

12% (7.8–19%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Back pain |

10 |

7.2% (4.0–13%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Chest pain |

8 |

5.8% (2.9–11%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Headache |

7 |

5.0% (2.5–10%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other responses |

91 |

66% (57–73%) |

|||||||||||||

|

All searches including term “pain” |

54 |

44% (31–47%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Multiple choices possible. † Free text responses. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Internet sites visited and trusted by 139 patients who searched regarding the problem for which they had presented to the emergency department

|

Responses |

Visited sites |

Trusted sites |

|||||||||||||

|

Number |

Estimated proportion (95% CI) |

Number |

Estimated proportion (95% CI) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Site types* |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Hospital sites |

55 |

40% (32–48%) |

76 |

55% (46–63%) |

|||||||||||

|

Commercial sites |

48 |

34% (27–43%) |

29 |

21% (15–28%) |

|||||||||||

|

University sites |

27 |

19% (14–27%) |

47 |

34% (26–42%) |

|||||||||||

|

Online encyclopaedias |

65 |

47% (39–55%) |

39 |

32% (21–36%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

25 |

18% (12–25%) |

12 |

8.6% (5.0–14%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

2 |

1% (0.4–5%) |

2 |

1% (0.4–5%) |

|||||||||||

|

Blogs |

13 |

9.9% (5.6–15%) |

4 |

3% (1–7%) |

|||||||||||

|

Forums |

2 |

1% (0.4–5%) |

0 |

0% (0–3%) |

|||||||||||

|

Specific sites† |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

WebMD |

12 |

8.6% (5.0–14.5%) |

13 |

9.4% (5.6–15%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

9 |

6.5% (3.4–11.9%) |

8 |

6% (3–11%) |

|||||||||||

|

Wikipedia |

6 |

4.3% (2.0–9.1%) |

4 |

3% (1–7%) |

|||||||||||

|

Other responses |

41 |

30% (23–38%) |

16 |

12% (7.2–18%) |

|||||||||||

|

Could not recall |

71 |

51% (43–59%) |

98 |

70% (62–78%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Multiple choices possible. † Free text responses. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Responses by 196 patients who regularly searched the internet for health-related information to questions related to the Internet Search effect on Medical Interaction Index (ISMII) or compliance with medical advice

|

Internet Search effect on Medical Interaction Index questions |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly agree |

No response |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

I receive more attention to my questions from health providers as a result of gathering information from the internet |

6 (3%) |

30 (16%) |

77 (40%) |

72 (37%) |

9 (5%) |

2 |

|||||||||

|

I receive more information from health providers as a result of gathering information from the internet |

8 (4%) |

27 (14%) |

80 (42%) |

67 (35%) |

10 (5.2%) |

4 |

|||||||||

|

Interactions with health providers have become more respectful as a result of gathering information from the internet |

10 (5.2%) |

39 (23%) |

80 (42%) |

53 (28%) |

10 (5.2%) |

4 |

|||||||||

|

Interactions with health providers have become strained as a result of bringing up health and medical information from the internet in my consultation (reverse scored in ISMII) |

17 (8.9%) |

64 (34%) |

69 (36%) |

36 (19%) |

5 (3%) |

5 |

|||||||||

|

Information on the internet helps me to communicate more effectively with doctors |

1 (0.5%) |

18 (9.3%) |

42 (22%) |

108 (56%) |

24 (12%) |

3 |

|||||||||

|

Information on the internet helps me to ask more informed questions to doctors |

1 (0.5%) |

5 (3%) |

31 (16%) |

115 (60%) |

40 (21%) |

4 |

|||||||||

|

Information on the internet helps me to better understand what my doctor is telling me during my consultation |

1 (0.5%) |

9 (5%) |

29 (15%) |

121 (62%) |

34 (18%) |

2 |

|||||||||

|

Gathering information from the internet about my health makes me feel empowered |

4 (2%) |

28 (15%) |

60 (31%) |

81 (42%) |

18 (9.4%) |

5 |

|||||||||

|

Gathering information from the internet about my health makes me worried and/or anxious (reverse scored in ISMII) |

10 (5.2%) |

50 (26%) |

55 (29%) |

61 (32%) |

15 (7.9%) |

5 |

|||||||||

|

Treatment compliance questions |

Never |

Rarely |

Sometimes |

Often |

Always |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Do you change your willingness to accept treatment from your doctor after reading information from the internet? |

72 (37%) |

43 (22%) |

63 (33%) |

12 (6.2%) |

3 (2%) |

3 |

|||||||||

|

Do you doubt your diagnosis or treatment of a doctor if it conflicts with information on the internet? |

110 (57%) |

43 (22%) |

31 (16%) |

8 (4%) |

2 (1%) |

2 |

|||||||||

|

Have you ever changed a treatment given to you by a doctor due to information obtained on the internet? |

135 (71%) |

39 (20%) |

14 (7.3%) |

2 (1%) |

1 (0.5%) |

5 |

|||||||||

|

Have you ever experienced a health problem as a result of using internet information? |

164 (86%) |

17 (8.9%) |

10 (5.2%) |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 8 – Linear regression analysis: effect of Internet Search on Medical Interaction Index (ISMII) total score, for 195 patients who searched regarding the problem for which they presented to the emergency department

|

Variable |

Estimate (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Age |

–0.01 (–0.45 to 0.38) |

0.87 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex |

0.09 (–0.35 to 1.96) |

0.17 |

|||||||||||||

|

Country of birth |

–0.01 (–1.48 to 1.09) |

0.77 |

|||||||||||||

|

Level of education |

0.01 (–0.33 to 0.38) |

0.90 |

|||||||||||||

|

eHEALS score |

0.39 (0.20 to 0.39) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 11 September 2017, accepted 6 April 2018

- Anthony M Cocco1,2

- Rachel Zordan1,2

- David McD Taylor3

- Tracey J Weiland2

- Stuart J Dilley1

- Joyce Kant2,4

- Mahesha Dombagolla2,5

- Andreas Hendarto2,6

- Fiona Lai2,3

- Jennie Hutton1,7

- 1 St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Austin Health, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Eastern Health, Melbourne, VIC

- 5 Goulburn Valley Health, Shepparton, VIC

- 6 Bairnsdale Regional Health Service, Bairnsdale, VIC

- 7 Emergency Practice Innovation Centre, St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

We thank Andrew Walby, director of Emergency Medicine, St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, and Thomas Chan, director of Emergency Medicine, Austin Health, for supporting this investigation in their emergency departments in 2017.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Shroff P, Hayes RW, Padmanabhan P, Stevenson M. Internet usage by parents prior to seeking care at a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011; 27: 99.

- 2. Khoo K, Bolt P, Babl FE, et al. Health information seeking by parents in the Internet age. J Paediatr Child Health 2008; 44: 419-423.

- 3. Goldman RD, Macpherson A. Internet health information use and e-mail access by parents attending a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006; 23: 345-358.

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 8146.0 Household use of information technology, Australia, 1996 [media release]. 14 Nov 1997. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mediareleasesbyTopic/E22ADBFC60B7EC2FCA2568A90013625B?OpenDocument (viewed June 2018).

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 8146.0 Household use of information technology, Australia, 2016–17. Mar 2018. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/8146.0 (viewed June 2018).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 8153.0. Internet activity, Australia, December 2015. Mobile handset subscribers. Apr 2016. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/8153.0Main%20Features5December%202015?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=8153.0&issue=December%202015&num=&view=) (viewed June 2018).

- 7. Ramaswami P. A remedy for your health-related questions: health info in the Knowledge Graph. Google (official blog) [website]. 10 Feb 2015. https://googleblog.blogspot.com.au/2015/02/health-info-knowledge-graph.html (viewed June 2018).

- 8. Sullivan D. Google now handles at least 2 trillion searches per year. Search Engine Land [online]. 24 May 2016. http://searchengineland.com/google-now-handles-2-999-trillion-searches-per-year-250247 (viewed June 2018).

- 9. Ekstrom A, Kurland L, Farrokhnia N, et al. Forecasting emergency department visits using internet data. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65: 436-442.e1.

- 10. Dugas AF, Hsieh YH, Levin SR, et al. Google flu trends: correlation with emergency department influenza rates and crowding metrics. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: 463-469.

- 11. Broadwater-Hollifield C, Richey P, et al. Potential influence of internet health resources on patients presenting to the emergency department [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med 2012; 60: S134.

- 12. Tan SSL, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e9.

- 13. Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the Web — the impact of Internet use on health care and the physician–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2007; 68: 218-224.

- 14. Stevenson FA, Kerr C, Murray E, Nazareth I. Information from the Internet and the doctor–patient relationship: the patient perspective — a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2007; 8: 47.

- 15. Russ H, Giveon SM, Catarivas MG, Yaphe J. The effect of the Internet on the patient-doctor relationship from the patient’s perspective: a survey from primary care. Isr Med Assoc J 2011; 13: 220-224.

- 16. Sommerhalder K, Abraham A, Zufferey MC, et al. Internet information and medical consultations: experiences from patients’ and physicians’ perspectives. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 77: 266-271.

- 17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Time spent in hospitals and emergency departments: St Vincent’s Hospital [Fitzroy]. MyHospitals [website]. 2018. http://www.myhospitals.gov.au/hospital/210A01450/st-vincents-hospital-fitzroy/emergency-department (viewed June 2018).

- 18. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Time spent in hospitals and emergency departments: Austin Hospital [Heidelberg]. MyHospitals [website]. 2018. http://www.myhospitals.gov.au/hospital/210A01031/austin-hospital-heidelberg/emergency-department (viewed June 2018).

- 19. Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHEALS: the eHealth Literacy Scale. J Med Internet Res 2006; 8: e27.

- 20. Scott G, McCarthy DM, Dresden SM, et al. You googled what? Describing online health information search patterns of emergency department patients and correlation with final diagnoses [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 66: S55-S56.

- 21. Backman AS, Lagerlund M, Svensson T, et al. Use of healthcare information and advice among non-urgent patients visiting emergency department or primary care. Emerg Med J 2012; 29: 1004-1006.

- 22. Scott G, McCarthy DM, Aldeen AZ, et al. Use of online health information by geriatric and adult emergency department patients: access, understanding, and trust. Acad Emerg Med 2017; 24: 796-802.

- 23. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Emergency department care 2015–16: Australian hospital statistics (AIHW Cat No. HSE 182). Canberra: AIHW, 2016.

Abstract

Objective: To determine the prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of health-related internet searches by adult emergency department (ED) patients; to examine the effect of searching on the doctor–patient relationship and treatment compliance.

Design: A multi-centre, observational, cross-sectional study; a purpose-designed 51-item survey, including tools for assessing e-health literacy (eHEALS) and the effects of internet searching on the doctor–patient relationship (ISMII).

Setting, participants: 400 adult patients presenting to two large tertiary referral centre emergency departments in Melbourne, February–May 2017.

Outcome measures: Descriptive statistics for searching prevalence and characteristics, doctor–patient interaction, and treatment compliance; predictors of searching; effect of searching on doctor–patient interaction.

Results: 400 of 1056 patients screened for eligibility were enrolled; their mean age was 47.1 years (SD, 21.1 years); 51.8% were men. 196 (49.0%) regularly searched the internet for health information; 139 (34.8%) had searched regarding their current problem before presenting to the ED. The mean ISMII score was 30.3 (95% CI, 29.6–31.0); searching improved the doctor–patient interaction for 150 respondents (77.3%). Younger age (per 10-year higher age band: odds ratio [OR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.61–0.91) and greater e-health literacy (per one-point eHEALS increase: OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06–1.17) predicted searching the current problem prior to presentation; e-health literacy predicted ISMII score (estimate, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.20–0.39). Most patients would never or rarely doubt their diagnosis (79%) or change their treatment plan (91%) because of conflicting online information.

Conclusion: Online health care information was frequently sought before presenting to an ED, especially by younger and e-health literate patients. Searching had a positive impact on the doctor–patient interaction and was unlikely to reduce adherence to treatment.